By Camilo Alberto Castro Gama

One of the most pressing challenges in Latin America is the fight against the trade of illicit substances. To support effective public policies, it’s essential to understand the most critical activities involved in the illicit substance markets.

A parallel economic system exists alongside legal global production networks, where criminal multinational enterprises (CMNEs) operate. These entities use legitimate corporate supply chains as vehicles for smuggling illicit products.

A common practice in several Latin American countries involves hiding contraband in export products such as coffee [1], bananas [2,3,4], and avocados [5], among others [6].

Global Mapping of Illicit Activities

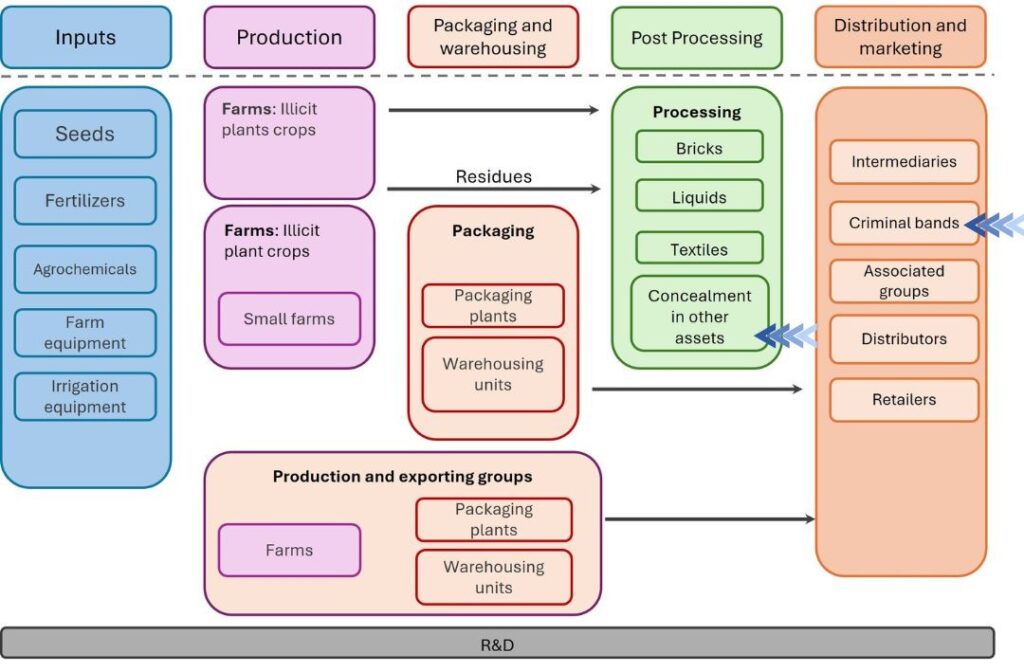

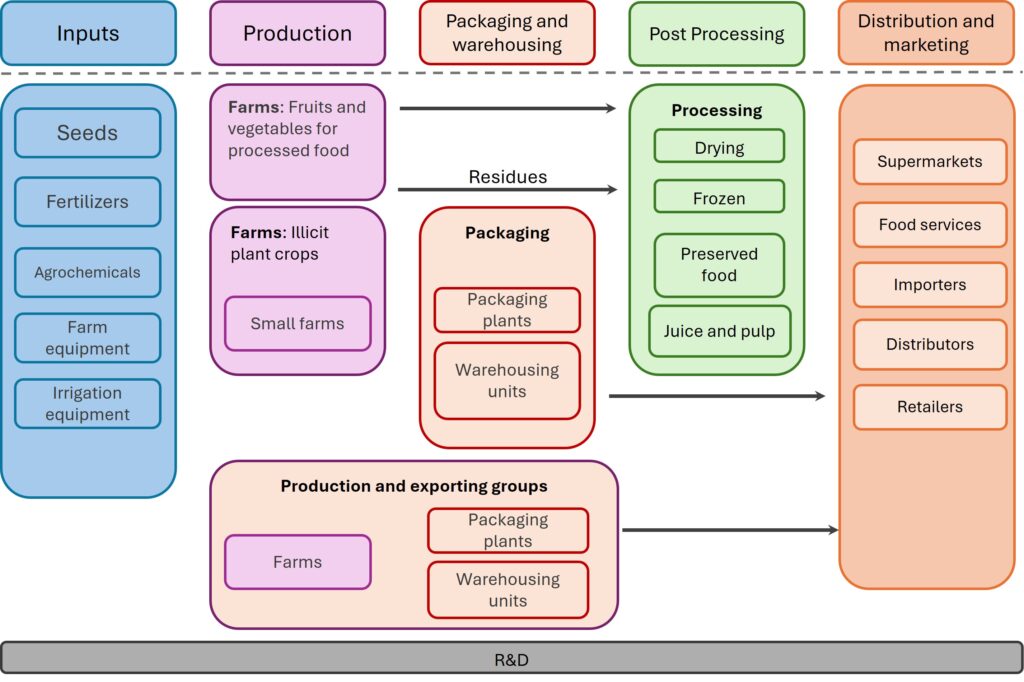

An analysis of the fruit and vegetable value chain reveals several key insights:

First, the production processes for legal and illegal goods are identical. Both follow parallel value-generating activities that ultimately serve the end consumer [7]. The inputs required for both value chains are similar, particularly the legality of the materials needed for cultivation and production.

In the next production stage, for both legal and illegal goods, part of the output remains for domestic consumption, while the rest is allocated for export.

“In the next step, the production process for legal goods involves activities related to product preservation, while for illicit goods, packaging and specific preservation methods are employed, depending on the concealment strategy.

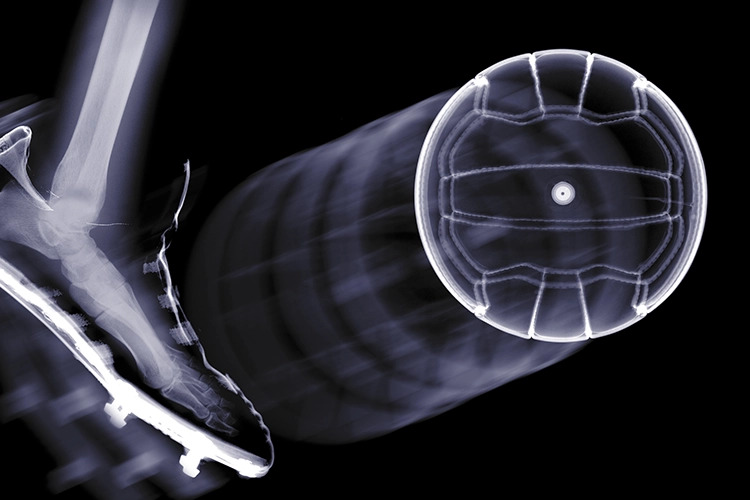

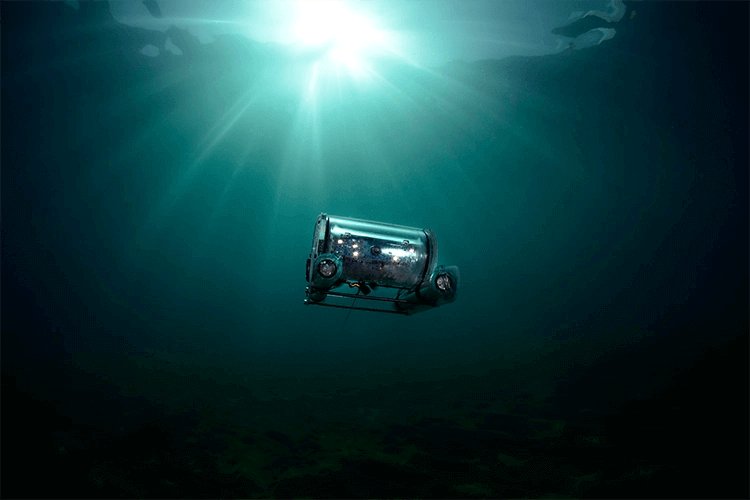

Legal products such as fruits or vegetables must be cleaned, sorted, preserved, and packaged in accordance with the importing country’s regulations [8]. In contrast, illicit products, such as narcotics, undergo additional procedures before crossing the border of the country of origin. These may include mixing with alcohol [9], embedding in textiles [10], packaging within other goods [11], or packaging to resist environmental conditions such as water or extreme heat [12], among others.

Upon arrival in the importing country, packaging is often altered for further distribution and commercialization. Dealing with illicit goods means additional steps to extract the desired substance.

For instance, chemical processes may be reversed to isolate the substance, or goods may be transported using maritime, air, or land routes [13].

Beyond these processes, repackaging for distribution and commercialization is required, resulting in residual by-products, which typically end up in surrounding city waters [14].

The final notable difference occurs in the research and development stage. Due to the nature of illicit substances, all stages of the value chain must be executed in novel and often covert ways.

This involves the concealment of the illicit substance and alternative methods to source raw materials, increase the purity of substances, and ultimately funnel the proceeds into the financial system.

Global Value Chains: What are they

The process of developing public policy becomes more effective when illegal activities are well understood. Additionally, Global Value Chains (GVCs) offer a conceptual framework that can support policymakers.

These chains are defined as all the activities that companies and workers engage in to bring a product from its conception to its final use and beyond [15].

These activities include research, development, design, production, marketing, distribution, and customer support.

The most significant aspect of this framework is the concept of the leading company, which acts as the primary concentrator of power and coordination within the chain [16].

A classic example is Apple, with operations distributed across countries like China, India, Thailand, and the United States, determining which companies can or cannot be part of the production process.

Mapping GVCs allows the identification of key players within the chain, critical activities (for example, those that generate the most profit or require greater control in execution), and the geographical areas where these activities take place.

Another example is the coffee industry, where selecting the planting location to achieve a specific flavor or, in the case of companies like Starbucks, deciding which companies are approved as coffee suppliers.

Through GVC mapping, more vulnerable activities to criminal groups can be identified.

In production activities, criminal groups may target smaller export companies and various types of goods, persuading them to transport illicit products or buy low-cost production to conceal the illegal substance.

Similarly, the mapping clearly shows where bribery and money laundering are most likely to occur, particularly at international borders, where illicit substances are frequently smuggled.

With this information, various groups focused on combating the trafficking of illicit substances can implement initiatives tailored to each stage, either aiming for deterrence or the persuasion of criminal activities.

References

- Euronews. (Agosto de 2020). Italian police intercept coffee beans stuffed with cocaine.

- Europol. (2022). 6.5 tonnes of cocaine found hidden between bananas in Colombia and Spain.

- Mackintosh, T. (Octubre de 2024). Gang smuggled £200m of cocaine in banana boxes. BBC News.

- The Guardian. (Septiembre de 2024). Over 40kg of cocaine found in banana deliveries to French supermarkets.

- Torres, A. (Marzo de 2024). More than 1.7 tons of cocaine is found hidden in avocado shipments heading from Colombia. DailyMail.com.

- Navarrete, M. A. (Abril de 2020). From Face Masks to Avocados, the Boundless Creativity of Drug Traffickers. Crime.

- Fernandez-Stark, K., Bamber, P., & Gereffi, G. (2011). The fruit and vegetable global value chain: Workforce development and economic upgrading. En G. Gereffi, K. Fernandez-Stark, & P. Psilos (Edits.), Skills for Upgrading: Workforce Development and Global Value Chains in Developing Countries. Durham: Center on Globalization Governance & Competitiveness and RTI International.

- Comisión Europea. (2024). Agricultura y desarrollo regional.

- Comisión Europea. (Marzo de 2023). CORDIS – Resultados de investigaciones de la UE. Nuevas técnicas para detectar cocaína mezclada con alcohol.

- PRADICAN. (Enero de 2013). Comunidad Andina. Manual de sustancias químicas usadas en el procesamiento de drogas ilícitas.

- Bernal, H. (2024). OAS. Camuflaje físico y químico de cocaína – Tráfico marítimo.

- BBC Mundo. (Diciembre de 2015). BBC Mundo. Las sorprendentes maneras de introducir drogas en Estados Unidos.

- Nájar, A. (Enero de 2015). BBC Mundo. Las insólitas formas de traficar droga a través de la frontera en México.

- Appleby, P. (2024, Abril). InSight Crime. La avalancha de cocaína se extiende por las ciudades de Europa, según las aguas residuales.

- Gereffi, G., & Fernandez-Stark, K. (2016). Global Value Chain Analysis: A Primer (2nd ed.). Duke Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness.

- Gereffi, G. (2022). On the Road to Global Value Chains: How Industry Dynamics Reshaped Development Theory. In M. Kipping, T. Kurosawa, & D. E. Westney (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Industry Dynamics.

- Barrientos, S., Gereffi, G., & Rossi, A. (2012). Economic and social upgrading in global production networks: A new paradigm for a changing world. International Labour Review, 150(3-4), 319-340.

- Henisz, W. J., & Zelner, B. A. (2005). Legitimacy, interest group pressures, and change in emergent institutions: The case of foreign investors and host country governments. Academy of Management Review , 30(2), 361-382.

- King, B. G., & Pearce, N. A. (2010). The contentiousness of markets: Politics, social movements, and institutional change in markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 36(1), 249-267.

- Lee, J., & Gereffi, G. (2015). Global value chains, rising power firms and economic and social upgrading. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 11(3/4), 319-339.

- North, D. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Voinea, C. L., & Van Kranenburg, H. (2017). Nonmarket Strategic Management (1st ed.). Routledge.

Note: This article is based on the forthcoming scientific article: Global Value Chains, Strategic Asset-Seeking, and Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions by Latin American Firms: A Gravitational Approach by Castro-Gama, C. A., Hartmann, A. M., & Trigos, F.

Author

Camilo Alberto Castro Gama. Ph.D. in Administrative Sciences from Tecnológico de Monterrey. He has developed research projects in the public and private sectors on intercultural management, global value chains, and economic development in Latin America. He has served as a faculty member in the Department of International Business at Tecnológico de Monterrey.