The first time I saw Rob Roggema was during a video call where he talked about an urban regeneration project in Rufino Tamayo Park, located in San Pedro, Nuevo León.

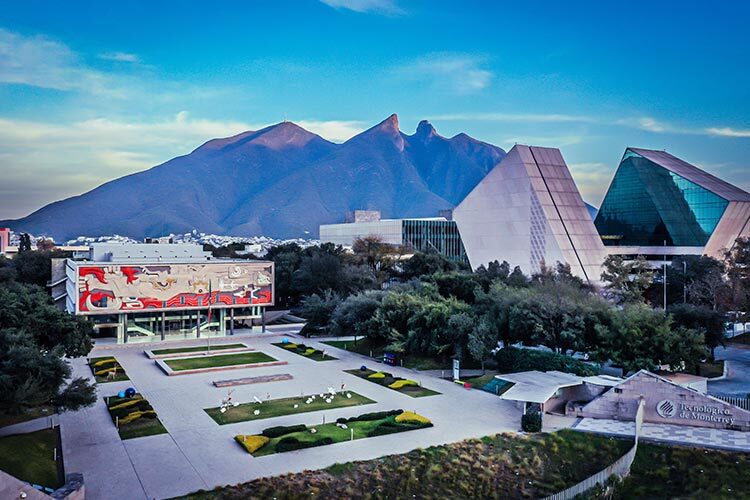

After almost a year, I discovered that we would have an in-person interview, so I suggested meeting at the Reflection Space at Tec de Monterrey. The work of architect Alberto Kalach blends concrete and wood.

It was fitting for the occasion because Roggema is an urban regenerator, and one of the unique features of this building is that it frames the iconic Cerro de la Silla as part of the space.

The researcher has been part of Tec de Monterrey’s Faculty of Excellence initiative since November 2022. The initiative aims to bring world-class professors to teach and participate in projects at the university. During our meeting, the researcher arrived with his 22-year-old daughter Inez. I noticed that despite it being 10 degrees outside, he was wearing a light jacket which suggested that the winter here might seem mild compared to what he is used to in Europe.

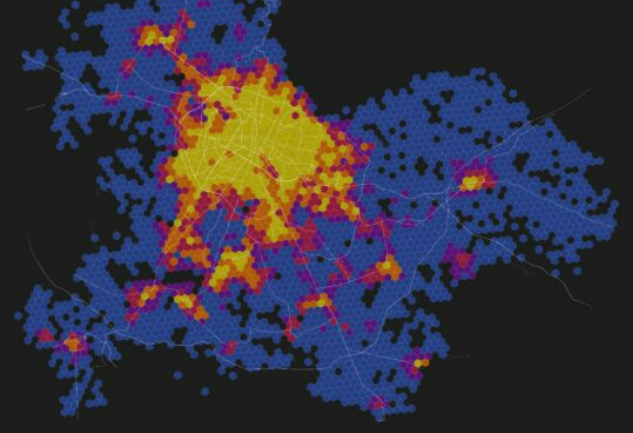

The area in which Rob Roggema has developed his work is regenerative culture, and he is one of the pioneers in mixing traditional landscaping externally and adapting it within urban environments, creating a new sustainable and comprehensive way of viewing cities, something that has led him to work in various countries and continents.

His vocation began in the Netherlands, where he was born and raised. Today, his work is about readapting cities and landscapes to make them as close as possible to their original state. For example, urban parks around streams that prevent flooding in the city are also home to native plants and animals, allowing a more comprehensive development of its citizens alongside nature.

Regenerating cities, a utopia?

Please explain to us in the simplest way what regenerative culture is.

It’s the concept of giving back to the environment and its systems more than what we take from it.

I always use this very clear example: We use a lot of water, but we contaminate it and pour it into wastewater, which degrades our environment; in the end, we won’t survive if the entire environment is degraded.

So, to turn clean water into a regenerative system, we need to give back more clean water than we extract. If we extract biodiversity, let’s make sure to give back more biodiversity.

For marginalized communities, it’s essential to have this natural environment very close to their place of residence. If they don’t have access to basic services like energy and water regularly, they extract all those resources from the environment without giving anything back, they will directly degrade their environment, which ends up threatening their survival in that place.

Tell us about how a regenerative project you worked on functions.

Food Río is an initiative I worked on almost ten years ago in Rio de Janeiro. It was meant to help inhabitants of marginalized communities in favelas grow their food.

There’s usually no access to healthy food in these neighborhoods, and processed products with high sugar content are consumed. The project consisted of building a food roof on a house in a favela through an aquaponic system, which involves the cultivation of fish and the growth of plants coexisting symbiotically. This way, people could fish and harvest vegetables and herbs regularly.

Now you are planning to do it in Mexico?

These systems can be applied here, too. We’re working on a project to replicate them in the Altamira neighborhood in Monterrey, not just on one roof but on the whole street.

The idea is to build it with students and the community so they learn to manage that system and feel it as their own.

How did you come to study regenerative culture?

After finishing high school, I explored biology, veterinary science, and oceanography. At a certain point, I became interested in geography and maps and then stumbled upon Landscape Architecture, a career I studied in the Netherlands. The problem was that it was focused on spaces outside the city, and after a couple of years, I thought there must be something more than landscape outside the city.

I went to Delft University for a year to study urban design, where I combined the principles of Landscape Architecture with urban contexts. That experience marked my professional life quite a bit.

Now, I understand the landscape ecosystem but can also apply it to urban space.

Researching from one continent to another

Why did you decide to work in government instead of pursuing a Ph.D.?

I couldn’t find a good option that I liked for a Ph.D., so I focused on working for municipalities and state governments to try to solve and research the problems that existed in cities.

In 2008, I started studying for my Ph.D., but I organized myself to spend half my time at work and the other half on my studies.

During this period, Roggema worked on initiatives such as implementing public policies that would allow cities to adapt urban planning methods to help them cope with the climate crisis and population growth.

Midway through your Ph.D., you were offered a research scholarship in Australia… That was a life change.

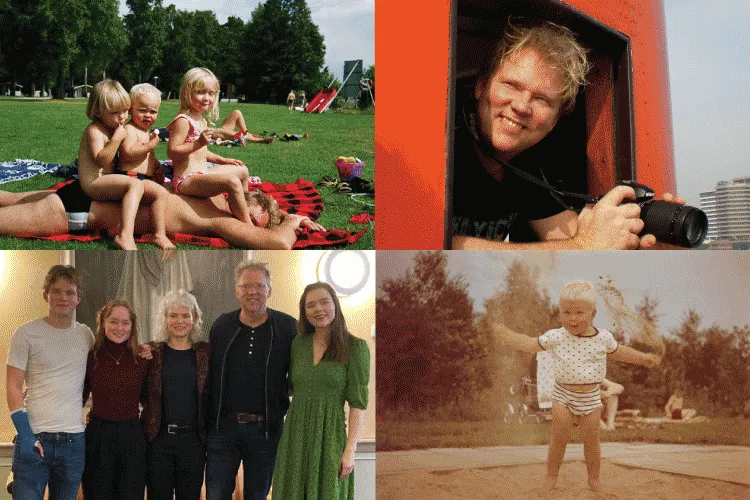

I had a permanent job in the government and could stay there for the rest of my life. My kids were between 5 and 7 years old, and my wife Lisa and I thought it would be a good idea to go for a year.

I requested permission at work, but they denied it because they didn’t want me to leave. In a way, it was a compliment, but it made our decision more difficult.

In the end, we went to Melbourne for three years. Six months for my scholarship, and then I developed a project and got a job at the University of Melbourne and my wife at the Milton Business School.

We had a great time, did great projects, and still have good friends and academic colleagues, so it turned out really well.

Were your kids still with you at that time?

Yes, although there came a time when my kids needed to go to high school, and the private system in Australia was expensive. Plus, our country’s public system is better, so we returned to the Netherlands.

Coincidentally, at the same time, I was offered a position as a professor of urban agriculture design, which also sparked my interest in urban food generation.

After three years, Rob Roggema’s life took another turn. A new opportunity arose in Sydney for a chair in sustainable urban environments, a tempting proposal combining sustainability, landscaping, and other aspects he was passionate about, so the Roggema family returned to Australia for three years. Later they returned to Europe again, and after a period of stability in the Netherlands, a call from Tec de Monterrey in Mexico changed things once again.

Mexico: the next step

What’s your opinion of our country?

I didn’t know Mexico. I realized it’s a highly underrated country with a rich culture, even larger than the culture of the United States or even Europe.

Mexico has a supportive community culture; it’s not egocentric. People want to do their best for everyone, and there’s always the belief that if someone else succeeds, I can also succeed.

In Europe or Australia, if you propose a project, people make excuses and rely on financing, but in Mexico, they first say, “Let’s see how we can make it happen,” in my line of work, that’s fantastic.

The foundation of regenerative culture is technical and social, and Mexico has a tremendous future in that regard.

What do you like most about Mexico?

There’s an immense wealth and diversity everywhere. Food is a crucial element of the culture, bringing people together to share and enjoy. I still don’t have a favorite dish because I enjoy the diversity, the different flavors, spicy food, and how it enhances the taste of the meal. So far, I feel that all Mexican food is my favorite.

Do you have any hobbies or activities you enjoy?

One of the things I love most is hiking in the mountains, something that is always done with someone else, to converse and enjoy the scenery.

In the Netherlands, I hike with my wife, just the two of us, whereas here, we have a shared experience with more people; it’s a kind of community, for hiking, working, and even eating.

Another thing I enjoy is photography; so many people do it better than me, but I still love it. I also have a favorite football team, Ajax, I’m always following them.

If you could change something about your trajectory, would you?

When I was a child, I was very shy, and I continued to be so even as I grew older. I remember when I had my first major presentation, and I was extremely nervous, even though I was over 20 years old.

In the end, that’s all in the past, but if I could do something differently, I would tell myself, “You don’t have to be shy; you shouldn’t worry about what people think of you; you just need to be yourself, and that’s more than enough. Some people will like you, and others won’t, but you don’t have to worry about it.”