My first impression of Sandra Ley is that she has a good sense of humor.

While waiting for the photo session to kick off at the School of Government and Public Transformation of Tec, at the Mixcoac campus in Mexico City, Sandra asks if she can leave her computer and backpack on a table. “Yes, no problem, it’s safe,” the guard replies; “And if not, we’ll find out,” she responds humorously.

Originally from Puebla, the PhD in Political Science has spent many years studying the high homicide rates and trying to understand phenomena such as lynchings or organized crime. At the same time, she can joke or understand references to Modern Family, the kind of series she enjoys in her free time.

She feels awkward in front of the camera, gesticulates, and wonders if she exaggerates. “I feel like kids who pull faces when you want to take their picture,” she says amidst the flash.

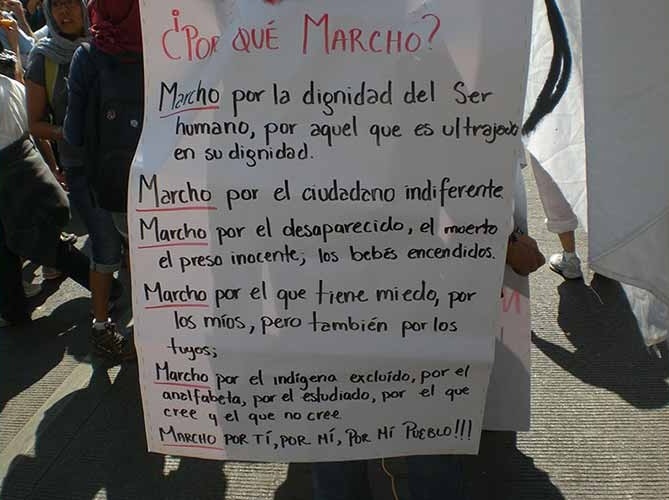

For Sandra, scientific rigor in research is crucial. Still, her work is not only based on large databases but also on listening to the various actors that form the complex web of national reality. If you look at her cell phone, you will find photos of different marches she attends to walk alongside victims or communities demanding security and justice.

She is also co-author of the book Votos, drogas y violencia (Votes, Drugs, and Violence), written with Guillermo Trejo, a professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame and director of the Violence and Transitional Justice Lab at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies.

In the book, which received the Democracy and Autocracy Best Book Award from the American Political Science Association in 2021, the researchers analyze how the country’s democratic transition set off unprecedented violence due to the networks of complicity between the State and organized crime.

For under a year, Ley has been a Distinguished Professor of Political Science and leads research projects on gender alerts, organized crime, criminal governance, and other types of violence in Mexico.

Investigating Violence: A Political and Personal Urgency

Why did you decide to study Political Science?

I had long considered studying medicine, but it wasn’t until my last year of high school that I realized I wanted to understand social problems. I was always involved in Model United Nations, which sparked my interest in politics.

When I started my degree in 2002, we were experiencing the beginning of the democratic transition. I was very interested in what was happening at the local level: states, municipalities and how democracy is built from the ground up.

When did you perceive that violence in Mexico was getting out of hand?

In 2008, I went off to do my doctorate, just when the most substantial surge of violence began. Being outside the country and seeing everything that was happening was very hard. I felt powerless, even guilty for not being there. That desperation led Guillermo Trejo (professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame) and me to gather data. There were no official databases, only the newspapers’ “Executómetros” (execution counters), and each one gave different figures.

What are the big questions that have guided your research?

I am interested in understanding how people react to violence. Do they participate politically? Do they do so through electoral or non-electoral channels? How do they resist? My doctoral thesis grew out of those questions. I have tried to understand the causes and consequences of violence from a political perspective.

The beautiful thing has been going down this path, trying to understand both causes and consequences from a political dimension.

How do you scientifically study something as elusive as violence and organized crime? Does the data exist to do the research?

The first challenge was the lack of data. We had to create our own databases using the press, local reports, and interviews. Above all, we had to talk to key actors: victims, activists, and journalists. Only in this way can you understand what the numbers cannot tell you.

Listening to the Victims, Understanding the Context

In your book, there are also interviews. What does this add to the data?

My work uses a mixed methodology: databases, interviews, and extensive demographic review. If I only compiled numbers, I couldn’t provide an interpretation. However, my work with collectives was about understanding an emotional part that numbers cannot tell.

One of the arguments I put forward in the article on protests, for example, is that the networks between victims and non-victims are fundamental to helping people take to the streets and demand justice, because otherwise you are left with your fear, instead of transforming anger into action.

What has close contact with victims’ collectives left you with?

A lot. Gratitude and a deep commitment. They have opened up their doors and their hearts to me. Walking with them, listening to them, has been transformative. They are my main inspiration for continuing to work.

Violence and Democracy: A Painful Relationship

In your book, Votos, drogas y violencia, you mention that drug trafficking in Mexico has existed since the 20th century and this level of violence was not seen. What changed?

The book allowed me to understand the way Mexican democracy evolved. The Mexican State was very intertwined with organized crime, and in the transition to democracy, no process was ever carried out to disentangle it. With the alternation of power, new governors came to power and placed new actors in key positions, some willing to confront crime, others with their arrangements. This breakdown of alliances generated violent competition for control and state protection. Without that protection being guaranteed, criminal groups turned to private armies. That caused the escalation of violence we are experiencing.

What would have to happen to break the link between organized crime and political power?

We should have had a transitional justice process. Mexican democracy did not have one, leaving a massive debt. Truth commissions have been regional, with little funding and a lot of politicization.

For example, we have had certain operations to take down the Secretary of Public Security, or municipal presidents corrupted by organized crime. However, we don’t follow up on them.

If I am going to punish or investigate specific individuals, I must do it. Whether they are from the opposition or my own party doesn’t matter. They should be willing to do it in all circumstances.

Mental Health Amidst the Investigation

How do you emotionally handle the impact of working with so much violence?

When I was a student, I didn’t have access to therapy or resources for self-care. Now, I am more aware of the need to talk it over and have support networks. In the research projects I lead with different organizations, I always allocate part of the budget to emotional containment processes, both for the team and for the people we work with.

Many young people say they wouldn’t have a family in Mexico. You said that being a mother changed how you see your work. How does your son influence your vision of the country?

For many reasons, it was difficult for me to decide to become a mother. Regarding my work, it’s hard to explain it to a six-year-old kid without disappointing him. But it has been nice to understand my work through his eyes, to help him understand why we want good police officers, or why we don’t wish to have weapons. An agreement in my house is that we will never have toy weapons. My son challenges me to hold onto optimism amid all this.

Almost a year into your role as a distinguished professor at Tec de Monterrey, what has been your experience with the students?

It has been exciting. The research stages aim to develop the students’ research skills, which looks pretty particular to Tec.

It has been very powerful for me to have that close connection with people who share my passion.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx