Corn tortillas are a symbol of Mexican culture—not only because they’re a staple of our diet, but also because they embody our identity. To make them, there’s a process called nixtamalization, which originated around 3,500 years ago in Mesoamerica. Now, a group of women researchers is working to modernize part of this process to make it more sustainable.

The goal is to reduce water and energy consumption and eliminate polluting effluents by replacing one of its components—while preserving tradition.

“Nixtamalization is part of Mexico’s intangible cultural heritage, so with this proposal we can help ensure it endures for future generations,” says Marcela Gaytán, research professor and head of the Carbohydrate Chemistry and Functionality Laboratory at the Faculty of Chemistry, Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro (UAQ).

Although corn and tortillas exist in other regions of the Americas, the Mexican way of making them—flat, thin, soft, and crafted from nixtamalized dough—is unique.

Nixtamalization offers many advantages: it releases vitamin B3, increases calcium bioavailability, improves flavor and texture, and removes toxic substances produced by fungi that grow on stored corn kernels.

However, the traditional method consumes a large amount of water—approximately three liters per kilogram of corn—and produces an effluent called nejayote, which has a highly alkaline pH, a high solid content, and an elevated oxygen demand, polluting water sources when discharged into drainage systems.

That’s why Gaytán began working twenty years ago on a project to transform nixtamalization into a more eco-friendly process through emerging technologies.

A New Device that Saves Water, Reduces Pollution and Boosts Nutritional Quality

The nixtamalization process consists of cooking corn kernels in water with 1% lime relative to their weight. The cooking lasts about 40 minutes, after which the mixture is left to rest for five to twelve hours. Finally, the kernels are rinsed, ground, and turned into dough—known as nixtamal—which serves as the base for tortillas, tamales, tlacoyos, and other traditional staples of Mexican cuisine.

“This process hasn’t changed in a very long time—over a century,” says Aurea Ramírez, a research professor in the Department of Bioengineering at the School of Engineering and Sciences (EIC) of Tecnológico de Monterrey, Querétaro campus.

At archaeological sites, the oldest remains of nixtamalized corn date back to between 1500 and 1200 BCE. This method made corn easier to digest and more nutritious, representing an early example of ancestral bioengineering.

Although over the years it has been adapted to new technologies—such as mass production in industrial plants—it remains quite similar to the ancient process, and few have focused on making it more sustainable.

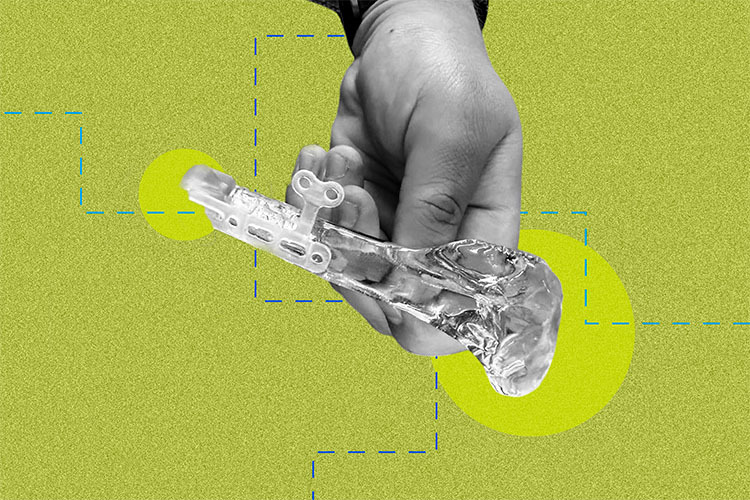

Gaytán and her colleagues developed a device that replaces the traditional pot, allowing the cooking process to use a minimal amount of water and lime, generate no polluting effluents, and reduce resting time to just one or two hours.

In addition, the solids that form during cooking stay in the water and are preserved in the nixtamal, boosting its nutritional quality. The device has been successfully tested in the lab.

“We achieve about 80% energy efficiency, and it runs on electricity instead of gas,” Gaytán explains. “Another advantage is that people who use it can keep the same equipment they already have in their tortilla shops—the only thing that changes is the pot.”

More Sustainable and Nutritious Tortillas for Mexicans

To verify that the dough obtained with their device is just as nutritious—or even more so—than the traditional kind, the researchers conducted a nutritional evaluation and fed tortillas made with both methods to an animal model.

“What we observed is that the animal model responded in the same way to both types of tortillas,” says Ramírez, who led this part of the project. “When we analyzed the calcium content in their bones in detail, we found it was slightly higher when they ate the ones made with our method.”

That’s because by keeping the solids from the cooking water in the nixtamal, the dough retains more fiber and antioxidants compared to the conventional process.

The researchers consider this an essential aspect of their innovation, as previous studies show that tortillas are sometimes the only source of calcium for certain populations—especially in rural areas where access to products like milk, meat, or seeds rich in this mineral is limited.

“If we’re aiming to modernize the technology behind such an essential staple of the Mexican diet, we must ensure that the end product remains nutritious, safe, and beneficial for the population,” says Ramírez.

Thanks to a multi- and transdisciplinary team from several institutions—including UNAM, IPN, Tec, and UAQ—comprising chemists, mechanical, electrical, and mechatronic engineers, biotechnologists, physicists, food chemists, and marketers, there is already a prototype of the device ready to be tested in tortilla shops in Querétaro and, later, across the country.

“Our goal is to transform nixtamalization with efficiency and sustainability—without compromising the quality and tradition this process represents for our country,” says Gaytán.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx