“Brachial plexus injury” is not a term we hear every day. For many people, this may be the first time they read it. Yet this relatively common condition, which can occur during childbirth, may leave lasting consequences on a child’s mobility.

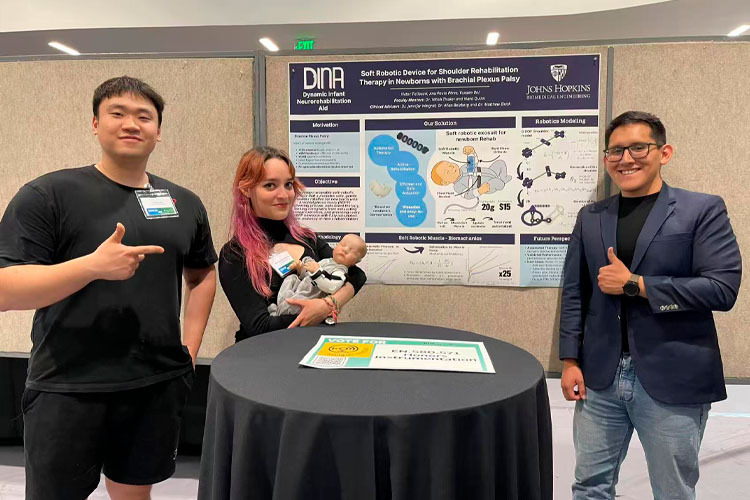

With the goal of offering a more accessible and safer treatment alternative for this condition, a group of researchers, including Ana Paula Pérez, EXATEC, graduate of Biomedical Engineering from the School of Engineering and Sciences at Tec de Monterrey, developed DINA (Dynamic Infant Neurorehab Aid), a robot designed to support the rehabilitation of newborns.

The brachial plexus is a network of nerves that originates in the neck and extends toward the shoulder. It’s part of the network that allows the brain to control the movements of hands, wrists, and arms. These nerves are especially vulnerable during childbirth: in breech or large-baby deliveries, they often overstretch as the baby exits the birth canal, leading to injury.

Long-term, this damage can cause limited mobility, chronic pain, or loss of sensation. However, if diagnosed in time, early rehabilitation can considerably reduce its consequences. That’s where DINA comes in, a soft robot that performs the necessary movements to promote brachial plexus recovery.

How DINA was born

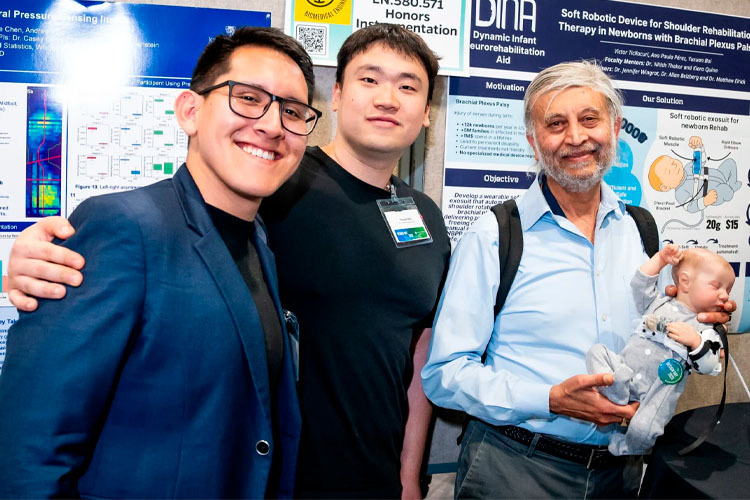

DINA began as a project in the Neurorehabilitation Engineering class of the Biomedical Engineering master’s program at Johns Hopkins University, where Ana Paula Pérez, Víctor Ticllacuri, Yuxuan Bai, and Michela De Marzi collaborated. The team decided to focus on this injury due to its low diagnosis rate in Latin American countries, such as Peru, where Ticllacuri is from.

“We might see a person who can’t move their arm due to a birth problem, but was never diagnosed because there were no specialists capable of performing this type of rehabilitation,” explains Ticllacuri.

In the United States, it’s estimated that between one or two out of every thousand births present this complication, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Technology inspired by natural movement

To design DINA, the team first modeled the movement of a newborn’s arm. They then consulted with specialists from the Kennedy Krieger Institute, in the US, who indicated the key movement for rehabilitation: rotating the arm from inside out, with the elbow immobilized.

With this information, they developed several prototypes. To guarantee the device’s safety, they opted for a soft structure, where movements are not generated by screws or pistons, but by the extraction of air inside the robot. This way, contact with the baby is gentle and controlled.

The team aims for hospitals to offer these devices for families to use at home. “Being a first-time mother is already stressful. Adapting to this new life with a neonate with complications and, additionally, performing a rehabilitation process without supervision several times a day can be overwhelming,” says Ana Paula Pérez. “DINA is designed to alleviate that burden on mothers, fathers, and caregivers.”

An accessible and global future

According to Ticllacuri, the materials used to manufacture the robot are readily available and low-cost, making large-scale manufacturing viable. The team hopes that, in the future, these devices can reach hospitals in Latin America and other regions where access to diagnosis and rehabilitation is limited.

Before that, they must overcome the regulatory process that medical devices intended for newborns face. Fortunately, they will receive support to advance on that path.

In September 2025, the team won first place at the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) innovation showcase. This recognition includes funding of 10 thousand dollars and participation in a specialized bootcamp to advance in the certification and development of the device.

“To this day we still can’t quite believe it,” says Pérez. “I think when we’re at the bootcamp we will realize the magnitude of what happened. Throughout this journey we’ve received lots of support from doctors, professors, and Hopkins’ Entrepreneurship Center. It’s been an incredible experience.”

Healing through international collaboration

For Ticllacuri, working with a multicultural team was key: “Having people from different countries enriched the project, because each one contributed different perspectives on how to address patients’ needs.”

Finally, Ana Paula Pérez invites other students to continue their academic projects: “Anything you do has the potential to help people if you commit to it.”

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more: marianaleonm@tec.mx.