Generative artificial intelligence (AI) has burst into schools, and although several years have already passed since its arrival, applications like ChatGPT remain a challenge for teachers and school administrators. Even without a clear-cut solution, the issue can be addressed by formulating hypotheses and engaging in responsible experimentation.

This was one of the reflections shared by Justin Reich, researcher and director of the Teaching Systems Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), during his keynote lecture, The Homework Machine: Navigating the Uncertain Future of AI in K–12 Schools, at the IFE Conference 2026, organized by the Institute for the Future of Education of Tecnológico de Monterrey’s Educational Group.

“We are entering a period of extended uncertainty,” Reich said. “Being honest about what we don’t know is better than inventing certainties.”

Reich knows the educational landscape well. He has also worked as a middle school teacher, is a former researcher at Harvard, and is the author of books such as Iterate: The Secret to Innovation in Schools and Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can’t Transform Education, in which he examines how technology by itself is not enough in education and how academic institutions adapt.

The Homework Machine: Listening to Those Who Live Education Every Day

Reich noted that when a new technology arrives in classrooms, the most common mistake is to seek out the opinions or perspectives of experts or administrators. Instead, he argued for listening to the voices closest to real learning: teachers, school staff, and above all, students.

That idea became the foundation of his research project called The Homework Machine, in which his team has interviewed more than 120 people across different schools in the United States.

“Our job was just to listen, to ask the question, ‘what is the experience like of having these new generative AI tools arrive in your schools’?” he explained.

The project’s findings have also been shared on the TeachLab Podcast, a platform where Reich presents the cases and firsthand accounts his team has been documenting.

Cheating and uncertainty: major challenges of AI in education

After the Covid-19 pandemic, as schools returned to in-person learning, they faced multiple challenges, including high levels of absenteeism, overburdened systems, and low teacher morale. As they were grappling with these issues, another major challenge emerged: the arrival of generative AI in late 2022.

ChatGPT began to be widely used to complete school assignments, while teachers lacked clear guidance on how to regulate its use in the classroom.

The use of ChatGPT or Microsoft Copilot for homework led many teachers to view their students with suspicion, as if they were cheating.

The speaker shared testimonies such as that of a teacher from San Francisco, who voiced her frustration: “I really love my students, and I really want to believe that they’re good and ethical people who care about their learning and their process. And then I hear myself being like, I’m pretty sure everybody is cheating.”

In another audio clip, a student in New York estimated that only four out of 20 classmates completed their assignments without using AI. “There are students who use it for everything, others who use it for about half of the work, and only a few who do the work legitimately, and even they use AI in some way,” he said.

Reich pointed out that this situation cannot be resolved on an individual basis, because it is not feasible for every teacher to have their own policy. Instead, he argued, collective solutions and shared responses are needed.

“I wish I could tell you that we have lots of good ideas and lots of good evidence. But we do not know what to do,” the speaker said with concern. “Ministries don’t know, and states don’t either. And the people who are most vocal about saying that they know what these things should be are the people I am most skeptical of.”

The four areas for working with and without AI

Faced with so much uncertainty, Reich called for an attitude rooted in humility—acknowledging that, for now, all that exists are hypotheses.

He suggested that schools adopt a model of “local science,” in which they gather evidence and make decisions based on those results. He also emphasized the importance of being transparent with parents, students, and colleagues.

“We’re going to do some experimentation with AI, but we don’t know if it’s the right idea or if this policy is going to work. Maybe we’ll change it in the next marking period or the next semester,” he said.

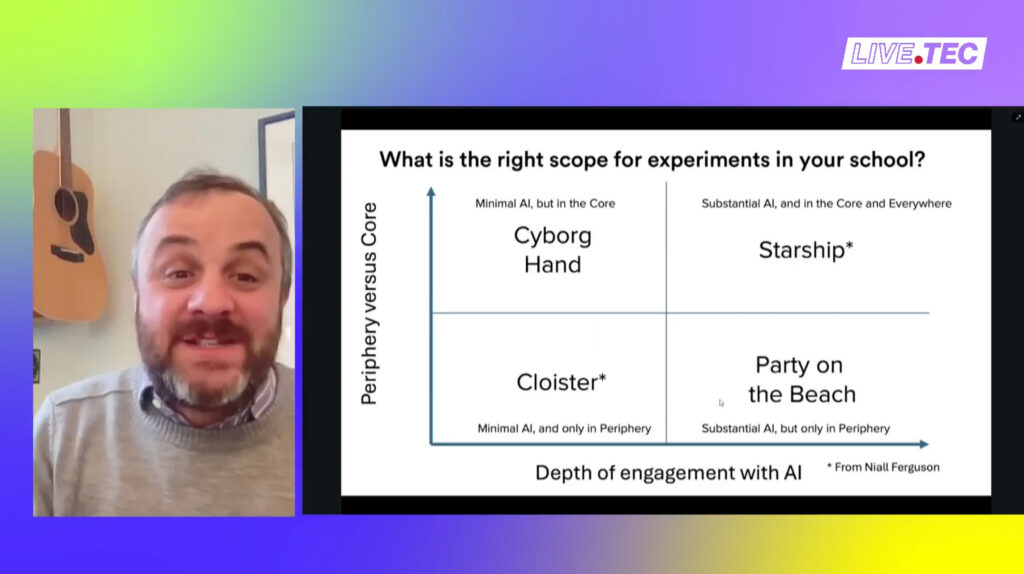

Reich presented a framework made up of four quadrants. On the vertical axis is the type of content, ranging from what is essential or “untouchable” in learning to secondary or complementary activities. On the horizontal axis is the level of AI presence in schoolwork, spanning from spaces where it is not used at all to others where it is used consistently.

The result is four scenarios that he presented as:

- Cloister: Spaces with no use of AI, designed to protect deep thinking and cognitive work without the support of machines.

- Starship: Settings where AI is used constantly and intensively to explore its full potential.

- Party on the Beach: Free use of AI is allowed, but only for secondary content or in peripheral areas of the curriculum.

- Cyborg Hand: Spaces that use AI selectively, only at key moments in learning where the teacher believes it adds pedagogical value.

“You can look at these four quadrants and ask: where do we want to place our bets?” Reich explained.

Reich closed by urging educational institutions to keep experimenting, noting that the arrival of AI in education implies a prolonged period of uncertainty. In other words, it will not be resolved in just a few months but will require long-term processes of validation.

“We have to keep asking ourselves whether we are seeing evidence of better work or deeper thinking in students, or whether AI is taking away from the most important things we are trying to teach them.”

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx