Cheese is one of the most diverse, famous, and beloved foods worldwide. Among its many attributes, this product carries a community of microorganisms—known as the microbiome—specific to each type.

In Mexico, a wide variety of cheeses contribute to the country’s culinary richness. However, our scientific understanding of these cheeses remains limited.

“European cheeses, like those from Italy, France, and Spain, have been extensively studied, but we know little about Latin American ones,” says Maricarmen Quirasco, a research professor in the Department of Food and Biotechnology at the Faculty of Chemistry of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), in an interview with TecScience.

For Quirasco, understanding the microbiome of two Mexican artisanal cheeses—cotija cheese from the original region and Ocosingo ball cheese—has been a primary focus of her research.

Since around the year 2000, the researcher and her team have employed microbiology, biochemistry, molecular biology, and bioinformatics to uncover the microorganisms inhabiting both cheeses to understand their role in maturation, flavor, texture, and aroma, as well as determining what makes them safe for human consumption.

“For me, making this contribution to the scientific knowledge of Mexican artisanal products is very important,” expresses the researcher.

The Microbiome of Original Region Cotija Cheese

Original region cotija cheese—which has this lengthy name to distinguish it from the industrialized version sold in supermarkets—is an artisanal cheese that’s been crafted for centuries in the Sierra de Jalmich region, between Michoacán and Jalisco, and is the cheese on which Quirasco’s team has primarily focused.

It is made from whole, unpasteurized cow’s milk, left to mature for at least three months to obtain the final product.

It has a hard texture, ranging from yellow to orange in color, with a salty taste and pungent odor, as well as a texture that crumbles when sliced. “Sensorially, it is very distinctive and appealing,” says the expert.

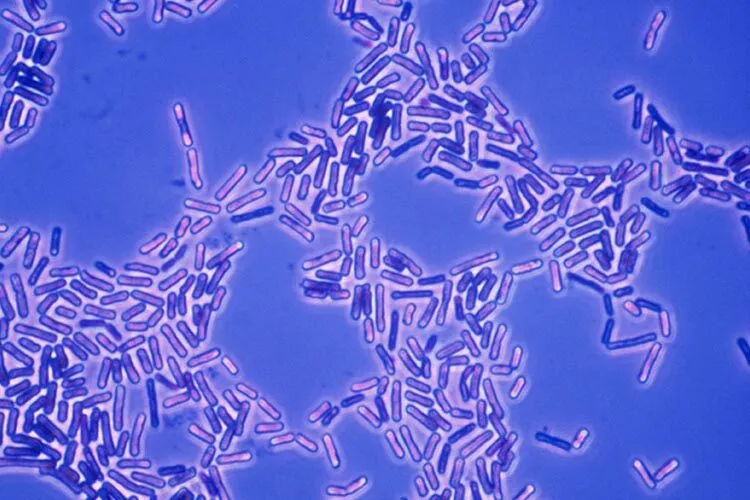

Through genomic analysis, they have defined its microbiome, primarily composed of bacteria from three genera—Lactobacillus, Leuconostoc, and Weissella—as well as yeasts—single-celled, microscopic fungi used in bread and other foods.

They have also characterized the dynamics established among the various species of bacteria and yeasts comprising this microbiome, finding that some are more prevalent at the beginning of maturation while others dominate toward the end.

“Some of these bacteria produce enzymes or compounds that seem to be relevant in producing the compounds behind its aroma and flavor,” explains Quirasco.

Compounds known to be involved in these characteristics include aldehydes, alcohols, carboxylic acids, and esters. In the case of artisanal cotija cheese, they appear to be produced by species of the genera Lactobacillus, Bacillus, and Staphylococcus.

The Bacteria that Make it a Safe Cheese

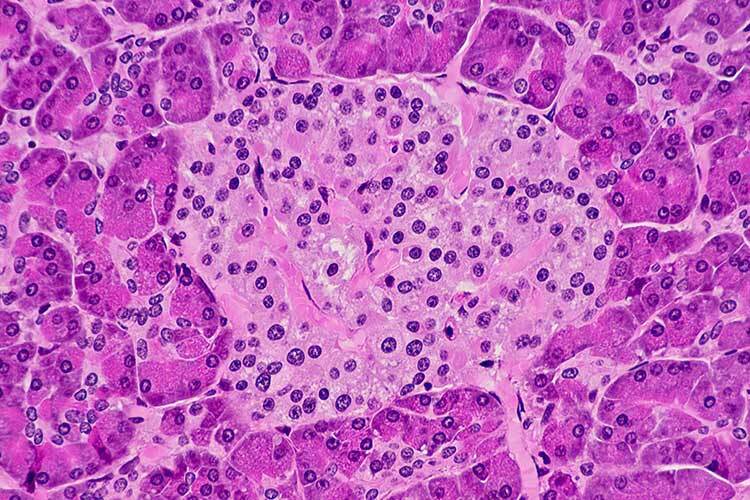

The group has also focused on understanding how these microbiome population dynamics result in the cheese being safe for consumption despite being made with unpasteurized milk.

Among their many findings are two bacteria from the genus Enterococcus that have antibiotic properties against pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella enterica; the former can produce toxins harmful to our digestive system, and the latter causes salmonellosis.

During cheese maturation, different species of lactic acid bacteria aid in generating acidity and moisture loss in the cheese, leading to the death of pathogenic bacteria.

“Some strains of the Enterococcus genus also function as probiotics that establish themselves in our gut and contribute to our digestive health,” Quirasco explains.

The presence of its various species of non-pathogenic bacteria in our digestive tract can stimulate it and keep it alert to combat microorganisms that can harm us.

According to the researcher, all these findings demonstrate that it is safe to produce mature cheeses with unpasteurized milk as long as hygienic processes are followed throughout all stages of production, maturation, and subsequent commercialization.

Uplifting Mexican Artisanal Cheeses

Understanding this microbiome has not only helped the researcher gain a profound understanding of it, but also paved the way for its commercialization.

In 2010, the Mexican government reviewed norm 243, which regulates the sale of dairy products and their derivatives, resulting, among other things, in the inclusion of matured cheeses, provided their safety is demonstrated.

Quirasco’s laboratory, together with scientists and experts from the World Health Organization (WHO), the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), UNAM, the University of Guadalajara, and the Center for Research and Assistance in Technology and Design of the State of Jalisco (CIATEJ), contributed scientific and epidemiological evidence to support the decision.

For Quirasco, her work not only represents her great passion for studying food science but also her desire to support Mexican artisanal food producers with scientific information that underpins the safety and richness of their products.

“Knowing that they are safe, that they possess sensory and chemical characteristics important to the consumer, will bring economic benefits to them and their region,” she says.