Around the same time that Grissel Trujillo was diagnosed with kidney cancer, she was awarded the L’Oréal-UNESCO Women in Science Fellowship for her work in bio-printing skeletal muscle.

Rather than discouraging her, the condition inspired her to persist, focusing her efforts on studies targeted at advancing science and, eventually, making organ bioprinting a daily reality.

Adversity was nothing new for Grissel Trujillo, one of Tec de Monterrey’s renowned researchers and co-founder of Forma Foods, a Tec company committed to creating printed meat alternatives for human consumption.

Grissel comes to the Alvarez-Trujillo Lab on the Monterrey campus with her husband and fellow researcher Mario Alvarez. I frequently see them happy, and today is no distinct, except that instead of lab coats, they are dressed neatly, as if to an award ceremony.

Mario waits outside for her, and she meets some of the students working in the lab (because even though it’s the second-to-last week of the year and the university is closed, science never stops) before taking a seat in the center of the laboratory.

The paths of research

Many initiatives have been completed in this facility, including chaotic printing. Can you clarify this particular matter to me? What does it consist of? What uses may it have?

Chaotic printing is a technique that we created at Tecnológico de Monterrey in collaboration with other students who had good ideas for its application.

To illustrate it, I often use the following analogy: imagine gently putting cream into a cup of coffee. On the coffee’s surface, you can observe how flows create structures. We employ chaotic flows, which, despite their name, are mathematically predictable and can quickly construct cellular patterns in tiny forms, much like a pastry chef creating a mille-feuille layer by layer.

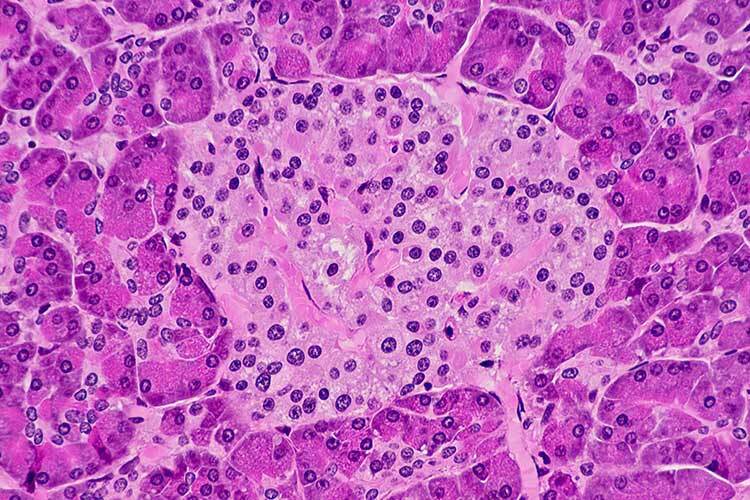

Our primary motivation has been to create functioning organs. We investigated strategies for printing biological tissues layer by layer without hurting the cells. If the cells are satisfied, they begin to communicate and build microtissues that are remarkably similar to real ones.

This method can also be employed in tissue regeneration treatment to test novel medications while reducing the number of animals used in research.

How did you transition from this to printing meat with Forma Foods?

Creating meat for human consumption was not our primary motivation. We wanted to create platforms for manufacturing tissues for medicinal applications. However, we naturally explored this use because our meat contains musculoskeletal tissue.

We had two patent applications, a dozen chaotic printing papers in trusted scientific publications, and a link with Dr. María Rubio from UNAM, a specialist on cultured meat. We founded Forma Foods in conjunction with Tec, led by Li Lu Lam, and with Carlos Ceballos and Joana Bolívar as mentors after being introduced to Saya Bio, the first investor.

We are now working on creating our ribeye, comparable to the meat we consume but generated in the lab.

Grissel studied Pharmaceutical-Biological Chemistry at Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León and received her master’s and PhD in Science from Tec de Monterrey. She conducted her postdoctoral study at MIT’s Khademhosseini lab, one of the leading laboratories in the nano area. She has published more than 70 papers in international journals, including Nature Reviews Materials, Scientific Reports, Biomaterials, Bioprinting, and Advanced Materials.

The laboratory that was born from a coffee

How did you start your career as a researcher?

Before completing my master’s degree, I got the opportunity to do an internship in India. Dr. Mario Álvarez and I explored the possibility of professional internships during my master’s program. He recommended I take advantage of the opportunity to go overseas, telling me that I would still have my position when I returned.

I considered Dr. Mario an aspirational person. He was still young, but he was the head of the Biotechnology Center and a member of the National System of Researchers. I wanted to be like him, but I never imagined we’d end up married and running a lab together.

He suggested I write a chapter for a book by one of his instructors. I was honored and glad for the chance; the topic was intriguing.

How did you establish the Álvarez-Trujillo Lab?

One day, I saw him working at Starbucks and told him I wanted to offer him a coffee to thank him for the chance to work on the book. I intended to buy him coffee and deliver it to his table, but he mistook it for an invitation to a date. Later, he invited me to lunch, and we became friends, then a couple.

While we were friends, I had an accident in the lab, which resulted in third-degree burns and a hospital stay. Dr. Mario spent the entire night caring for me. At that point, I knew I wanted him to be with me for the rest of my life.

We married, and he eventually traveled to Boston as a visiting professor while I went as a postdoctoral researcher. We found a new world of tissue engineering, bioprinting, and hydrogels there. We began working together, and when we returned in 2017, it felt natural to continue working on those initiatives as the heads of a research laboratory.

Pushing limits

In 2019, you went through a challenging time…

After Mario had an MRI for a back injury, I wanted to be sure everything was okay with my spine. My back was good, but they discovered a growth in one of my kidneys that turned out to be malignant. My grandma died from kidney cancer therefore it was decided to remove the entire kidney.

Thankfully, it was identified in time, and while this treatment saved my life, losing an organ was traumatic. Cancer forced me to think things through and realize that I was ready for practically anything and could handle it.

How did your life change from then on?

Before then, I was insecure and suffered from impostor syndrome. I felt unworthy of all I had accomplished, of becoming a professor or researcher. This experience opened my eyes and taught me I could handle much more. I was also thankful to everyone who has always been close to me, including my mother and husband and the institution where I work, which provides an enriching atmosphere for my work.

The Tissue Architect

Tell us a bit about yourself as a child.

I was always very dedicated, did my schoolwork, and was an honor guard member. I had wanted to be an architect and then a psychologist since I loved listening and giving good advice. It appears disconnected from what I do now, but when you think about it, it has to do with mentorship and education.

Born in Matamoros, I attended primary school in Gómez Palacio before receiving a scholarship to study at PrepaTec in the Laguna region. There, I had excellent biology and chemistry teachers. My mother is a veterinarian, so she explained how cells function and grow. At some time, I stated, “I want to pursue a career in this.”

It seems your mom influenced you a lot…

My mother has been a wonderful role model and mentor and has taught me a lot personally and professionally.

She had a problematic relationship with my dad, and she was subjected to physical abuse. One day, my dad abandoned the three of us: my mother, brother, and me.

My mom was a superhero. She was working on her Ph.D. while we lived in Gómez Palacio, and she took us to school by bus, then went to work, picked us up, cooked, and returned to the university… She traveled eleven buses daily and planned her schedule to ensure she had enough money for school and fees.

She was always a strong lady who was not resentful; when my father reappeared, she divided her feelings for him and pushed us to respect him, encouraging our visits to him. I tell her she is a saint.

In the end, what dream do you want to see fulfilled?

I envision leading a research center in Mexico where people worldwide work, motivated to change the future.

This career is a marathon, but almost like relay races, one after another. I would love to contribute a step on that ladder, inspiring the next Nobel Prize winner who may already be forming in our research group.