The pandemic has revealed the inequity in vaccine distribution. Every year, there are 5 billion doses of all kinds produced in the world, which are still not enough to immunize the whole population. To bridge the gap, Tec graduate Pável Marichal Gallardo is using his company ContiVir to push innovative technologies that can help manufacture vaccines and gene therapies in a way that is decentralized, continuous, efficient, and cheaper.

Lower cost vaccines

According to Our World in Data, 20 months into the Covid-19 pandemic, only 5.9% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose of the vaccine.

Although the World Health Organization (WHO) hopes to accelerate immunization so that 40% of the world’s population will have received a complete scheme by the end of the year, the challenges of production, distribution, and logistics are a bottleneck that make reaching that goal difficult.

The Tec graduate explains that there are a handful of factories in the world which produce vaccines and gene therapies and distribute them worldwide through very complicated logistics.

With the health crisis, the picture became more complicated because already scarce supplies were redirected to almost completely manufacturing vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. This has led to global shortages and the emergence of new mutations.

“The solution is to simplify, miniaturize, and decentralize those factories to quickly and efficiently increase production abilities in the global South,” Marichal Gallardo says in an interview with Tec Review.

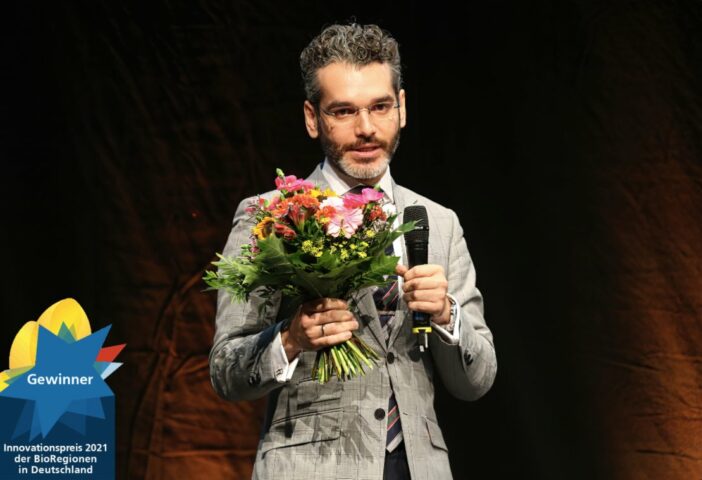

He and his partners Felipe Tapia, whom he met while doing his PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics of Complex Technical Systems in Magdeburg, Germany, and Tec graduate Julián López Meza, responsible for the business, push for a more equitable supply model.

The team wants to replace large bioreactors and slow purification equipment that use protein methods and technologies designed in the 70s and 80s with two technologies they developed during their PhD studies.

Recent innovations from the lab

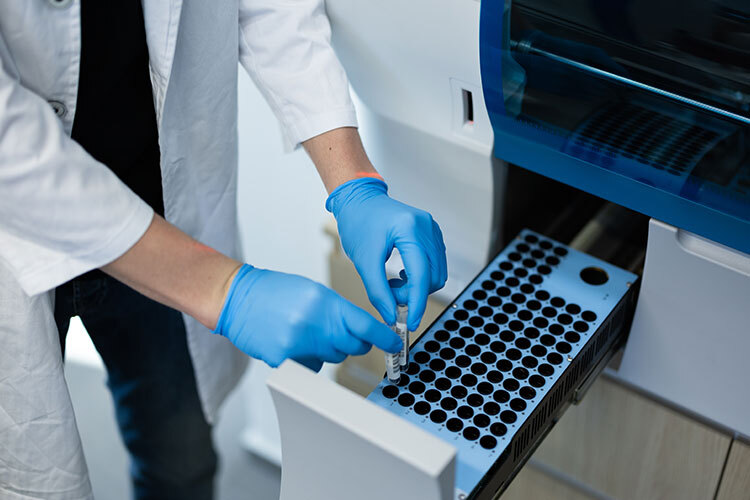

One technology, created by Felipe Tapia, is a tubular reactor 1.5 millimeters in diameter that replaces large batch bioreactors and accelerates the manufacturing process.

The other is Marichal Gallardo’s CaptuVir device for purifying viral particles.

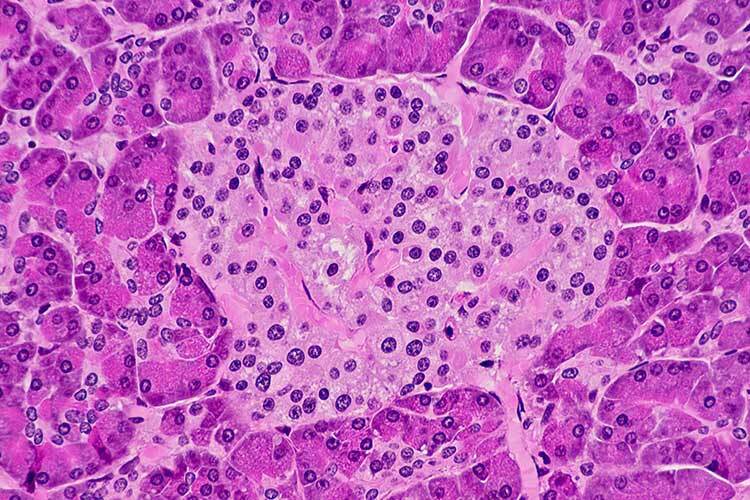

This biotechnologist explains that mammalian cells, yeasts, and bacteria are usually used to grow the desired genetic material, such as a protein (which the organism would not naturally produce), complete viruses, or a fragment of a virus (for a vaccine).

Once they have multiplied, the particles are isolated, concentrated, and delivered at a high level of purity so that the recipient organism generates an immune response in the case of vaccines (e.g. by producing antibodies) or so that it begins to express certain proteins (also for vaccines or for gene therapies).

With the technology, Pável Marichal Gallardo proposes using disposable devices based on membranes with a universal recipe he created to achieve high efficiency and speed in the purification of particles. This translates into more treatments without the need to expand capacity and manufacturing processes and can adapt to different viruses without the need for time-consuming and costly readjustments.

The ContiVir members were awarded the 2021 BioRegion Innovation Award in Germany for their purification technology.

The dream of Pável Marichal and the team is to contribute to the installation of these technologies in university hospitals and certified clinics so that therapies and vaccines are produced on site for each patient.

Production of particles for Covid-19

When the pandemic began, they collaborated with different research groups to produce and purify viral particles for Covid-19.

Their technology applies to mRNA molecules but is much better integrated into inactivated vaccines such as Sinovac and CanSino or those using viral vectors such as AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson.

They worked on a virus-like candidate in a project led by Professor Judith Gottwein of the Department of Infectious Diseases at the University of Copenhagen Hospital in Amager and Hvidovre.

Laboratories where SARS-CoV-2 multiplies need level 3 safety. Since ContiVir has level 2 safety, they chose to produce virus-like particles that do not pose any risk.

They multiplied cells with the genetic information so that they could produce the capsid, i.e. the outer part of the virus.

“We obtained a hollow sphere that looks like the virus on the outside and has all the antigenic properties that produce immunity but is hollow on the inside so that it can’t multiply,” Marichal says.

In another project, they helped colleagues from the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences’ Department of Immunology and Microbiology at the University of Copenhagen to purify the inactive SARS-CoV-2 virus.

They returned the pure, concentrated virus with analytics so that pre-clinical trials on animals could begin in Denmark. The collaboration is ongoing.

Yellow fever vaccine tests

Another proven ContiVir success story is the mass production of viral particles for the yellow fever vaccine.

Although it was developed in 1930 by Max Theiler, for which he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1951, its production is extremely inefficient because the method requires a lot of space, equipment, and supplies.

30,000 people still die every year from this viral disease transmitted through mosquito bites from Aedes aegypti, Haemagogus, and Sabethes mosquitoes in tropical areas of Africa and Latin America.

“The vaccine is still produced in embryonic chicken eggs. The problem is that one egg gives you between 100 and 300 doses. It’s even worse for influenza because it’s one dose per egg. It’s a very slow and very manual process,” explains the Tec graduate.

With the technology created by this Mexican, they were able to purify around 100,000 doses in a few hours with a small device.

The era of personalized medicine

Gene therapies often use Adeno-associated virus, which is harmless to humans, as a transport method to insert genetically modified material and for patients to begin expressing the appropriate proteins and correcting defects.

Cancer is one of the representative cases for this therapy because sometimes a patient’s immune system does not recognize cancer cells.

“Cells are extracted from the patient, their cells are modified in the laboratory with a virus, the correct genetic material is inserted so that they can recognize and attack the cancer cells, they multiply in the laboratory, and then they’re given to the patient.”

This treatment causes fewer side effects because it works with the patient’s cells. The problem is that they are not available to most people. Treatments today cost up to 2.1 million dollars.

If their technology passes pilot tests, they could help create miniature factories distributed around the world.

The next stage: incorporating the company

The biotechnologist says that the efficiency of the particle purification technology has already been tested and they are now finalizing the development of the product, but they have not scaled it commercially yet.

“We need to learn what users require and what the market needs. We need to refine how quickly the customer needs the product or whether it requires direct on-site or remote technical assistance,” says the Tec graduate.

The European Union and the German government gave them 1.6 million euros to take the academic project to its commercial stage.

The project is part of the Max Planck Institute, which is providing them with laboratory space, legal and business advice, and patent advice during this transition period.

That funding will end in May 2022. They will then incorporate themselves as a private company and look for more financing from venture capitalists or other investors.

Meanwhile, this time has served them to refine technologies and look for investors and future customers, with the advantage of knowing that they have had satisfied users.