For many of us, labels on ultra-processed foods often feature ingredients with unpronounceable names and mysterious origins.

Each country establishes food legislation to prevent these ingredients from hiding health risks. This process takes time and results in different decisions. A recent example is that California in the United States banned four commonly used food additives, three of which are still consumed in Mexico.

What Are Food Additives?

Food additives don’t provide nutrients but are added to food for technological purposes, such as maintaining freshness, preserving it, adding color, sweetening, or making it more appealing to taste and sight.

The substances that have until January 1, 2027, to be removed from California are potassium bromate, used by the bread industry; propylparaben, a preservative; red dye number 3, commonly found in candies; and brominated vegetable oil, which persists in some sodas. The reason is that recent animal studies have linked these substances to reproductive system issues, cancer, and neurobehavioral disorders, such as hyperactivity. Mexico doesn’t allow potassium bromate but is open to other compounds.

In this regard, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) concluded, after a series of toxicological studies, that brominated vegetable oil in food is unsafe and announced a review of the other substances.

Scientific Evidence to Create Laws

It’s not the first time the relevance of an additive has been examined. In fact, it’s one of the tasks of the FDA and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Ideally, agencies should review the most current scientific evidence and, when necessary, modify their recommendations to ensure food safety.

Sara Guajardo, a food technology specialist and national director of the Food Engineering program at the School of Engineering and Sciences, mentions that Mexico has a list of permitted additives with their conditions of use.

When there’s suspicion that some may be dangerous, the Ministry of Health (Ssa, in Spanish), through the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risks (Cofepris, in Spanish), explores various studies and international recommendations, such as those from the Codex Alimentarius, a compendium generated by a committee of experts from various countries designed to protect consumer health and international food trade equity.

Yolanda Chirino, coordinator of the doctoral program in Biomedical Sciences at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, explains that the evidence used for such purposes is published in rigorous scientific journals.

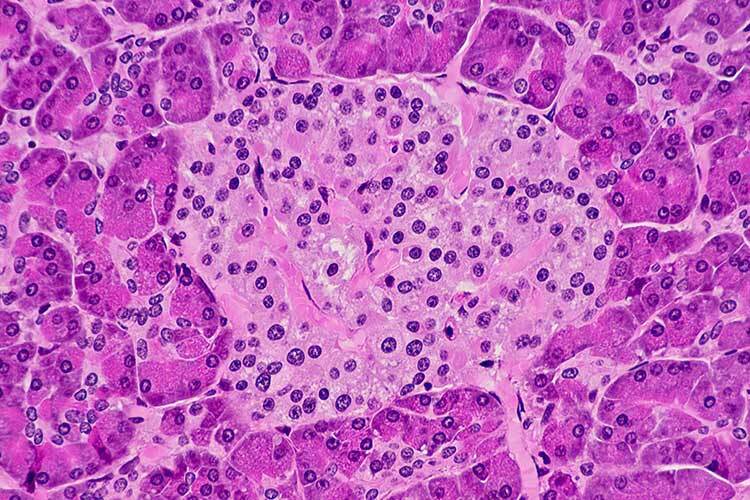

She details that most studies are at the in vitro and in vivo levels; the former is conducted with cell cultures to observe the chemical and biological properties of the chemicals, while the latter uses animals, particularly rodents, to administer the additive and evaluate its effects or toxicity.

The scientist notes that these results cannot be extrapolated to human cases. Still, robust evidence with in vivo models is a tool to predict effects on people under certain circumstances.

Determining if a substance poses a health threat through experiments with humans is complicated, partly because many studies that could show causality are not ethical, or when they are, they take many years of strict monitoring of groups of individuals. ‘Without so much evidence in humans, we make decisions a bit more slowly based on what we know from animals,’ she says.

For example, this year, the World Health Organization (WHO) concluded, after a systematic review of 283 studies, some observational in people, that the consumption of artificial sugars is long-term related to higher weight and obesity risk, which could harm people; it also increases the risk of premature births.

The case of the white dye Chirino is also a professor at the Faculty of Higher Studies (FES) Iztacala of UNAM and head of the Carcinogenesis and Toxicology Laboratory in the Biomedicine unit. She studied titanium dioxide, an additive approved by Mexican standards for use in food to improve its appearance. It is added in amounts less than 1% of the weight of the food.

In the last decade, she says, research shows that this additive may not be safe for humans. EFSA is considered so because evidence in experimental models suggests that in low doses administered over sustained periods, it is potentially toxic, especially in the gastrointestinal system.

Some European countries prohibit it, but there is no recommendation in Mexico, and its labeling is not mandatory. That must change, but it is not enough to imitate the legislation of other countries; a modification is required according to the national context.

Chirino explains that identifying how much risk exists in a region requires local scientific analysis. The first step, she says, is to quantify the additives in foods for sale in Mexico that may include them.

A guide for industry practices is the Acceptable Daily Intake, known by its acronym ADI. This parameter indicates the maximum amount of a substance a person can consume throughout their life without causing appreciable harm to their health. As a precaution, this measure usually has a wide margin between the considered safe dose and the authorized one.

The problem with doses is that sometimes additives are widely used. Titanium dioxide, for example, is in toothpaste, some multivitamins, and sometimes ibuprofen; it has also been identified in the quintessential Mexican food: tortillas. Therefore, Chirino conducted a pilot study to assess the presence of this additive in tortillas in the State of Mexico and detected it in some regions. Similar evaluations have been done in Europe and the United States to estimate human food exposure, and they found that this additive is very present in candies, a reason to pay attention to its intake in childhood.

However, understanding the risk of a chemical substance depends not only on the degree of exposure but also on understanding its interaction with other diseases.

This was demonstrated for tumors in a study published by Chirino in 2016. She and her collaborators observed that in mice with colon cancer, the additive exacerbated the number of tumors, while healthy mice did not develop them. ‘That’s why the emphasis is that if our health is poor and we give it some stimuli, it can potentiate the disease.’

Other research shows that mice with a high-fat diet develop liver damage, but those who eat the additive have more damage.

Following Laws and Breaking Paradigms

Guajardo, who has taught Food Legislation, comments that it is not enough to have rules; they must be respected. Regarding the correct use of additives, an example would be that if the safety of a substance was tested at room temperature, it should not be applied to products that will be baked at 180 degrees because the evidence no longer guarantees that it is harmless.

She also points out that the work of food engineers is to look for alternatives for additives that are not considered safe. Something possible through processes, natural ingredients, or packaging that provide the functionality of the additive. The problem, she says, is that sometimes the technology is not applied because the product’s final cost does not cover this adjustment.

In addition, the scientist clarifies that creating new ingredient options takes time, resources, and money. Developing a product or discovering the use of a natural element involves studying molecules, proving their effectiveness, conducting toxicity tests, and safety reviews.

On her part, Chirino believes that science and technology can replace ingredients. Still, in cases like titanium dioxide, removing them from the market is difficult because it is a cheap and versatile additive that generates significant global profits.”