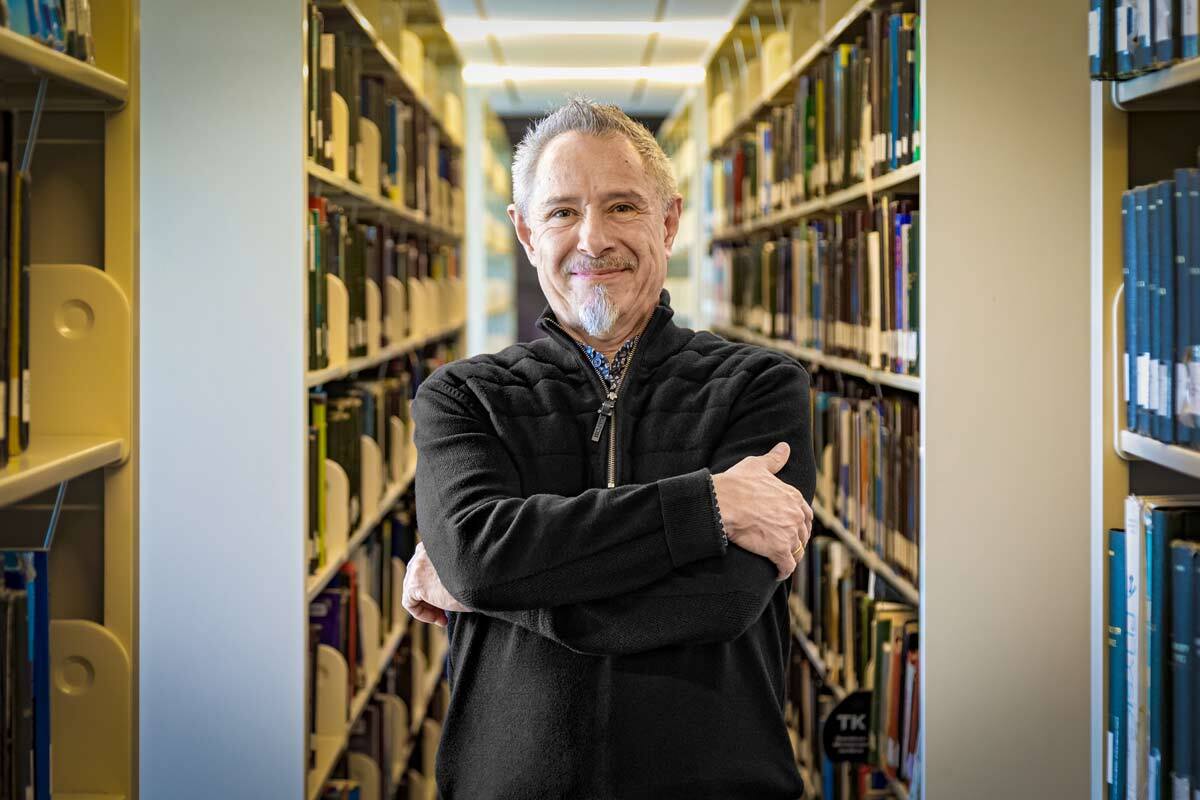

Learning takes time, patience, and countless mistakes—an essential process that is being undermined by the indiscriminate use of artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT, warned Professor Dominique Boullier.

Boullier is professor emeritus of sociology at Sciences Po Paris, where he has witnessed firsthand how generative artificial intelligence (AI) is driving profound and potentially irreversible changes across education systems worldwide.

During his keynote lecture, “Digital dehumanities in the making,” delivered at the IFE Conference 2026, organized by the Institute for the Future of Education (IFE) at Tec de Monterrey, Boullier argued that education systems are accelerating their adoption of generative AI at a pace that ultimately harms learning itself.

“I really miss the times when we had control”, Boullier said at the start of his presentation. “Now we don’t have control over anything. That’s really the core of the problem we face with AI systems.”

Generative AI in Education is Not Like a Calculator

One of Boullier’s first experiences with educational technology was in 1997. As a professor at the University of Technology of Compiègne in France, he helped create one of the country’s first digital degrees. Back then, Boullier recalled, educators were in charge of organizing technological systems.

Not only did they require companies like IBM to accept their requirements for these systems to be truly useful to them, but their team even went so far as to reject software updates. Their argument was that teachers couldn’t adapt to constant changes in their classrooms.

This was the era when institutions controlled production. Now we are far from this reality, Boullier explained. AI platforms are not only entering the market disruptively, but they also leave users with the task of dealing with the consequences.

One of the main consequences is at the hands of what he calls “rogue AI,” companies that don’t take responsibility for the harm they can cause and often act without guaranteeing a quality product.

For this reason, Boullier doesn’t agree with the argument that AI is just another tool, like a calculator. “You didn’t have to check a calculator’s results,” he said, citing the “hallucinations” that many users have come to expect from the platforms.

Large Language Models (LLMs), the expert argued, “are a dead end.” These systems generate responses that not only can be incorrect, but also lack a point of view and have no reference to the real world.

“The opinion of someone on the street, an influencer, a professor, and everyone else is horizontally reduced to the same value,” the sociologist argued.

Boullier also rejected the idea that the more we use AI, the more control we can gain. In his perspective, this loss of control has four central axes: we don’t control the rules, the sources, the quality of data it uses, or the reasoning of the systems.

AI doesn’t use common human reasoning. Simply put, Boullier added, it performs statistical predictions of the next words. Nor does it know how to distinguish between quality sources or data and others that haven’t been verified by experts. The information it uses “is only valid through volume. It’s brute force, which is the most basic level of technology.”

Toward Educational Survival

A particularly concerning phenomenon is what the expert called “model collapse”: when AI learns from its own productions and generates increasingly derived responses from its own logic. “AI is becoming autophagic. It’s eating itself,” he declared.

Boullier doesn’t expect the technology to be completely rejected, but he does hope that education systems find ways to regain control and responsibility. He proposes three key strategies:

- Explicitly reassess specific educational problems before adopting any technological solution.

- Establish and enforce explicit conventions in each institution, involving all actors in a discussion about values and principles.

- Create verified knowledge bases within institutions, rather than blindly relying on external systems.

More than anything, Boullier hopes that universities will slow down the pace of adoption at this critical moment and not be driven by the fear of falling behind.

To close, he gave one last warning: if they don’t regain control, education systems risk forming generations that have unlearned the fundamental cognitive capacities that define critical thinking and deep learning.

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx