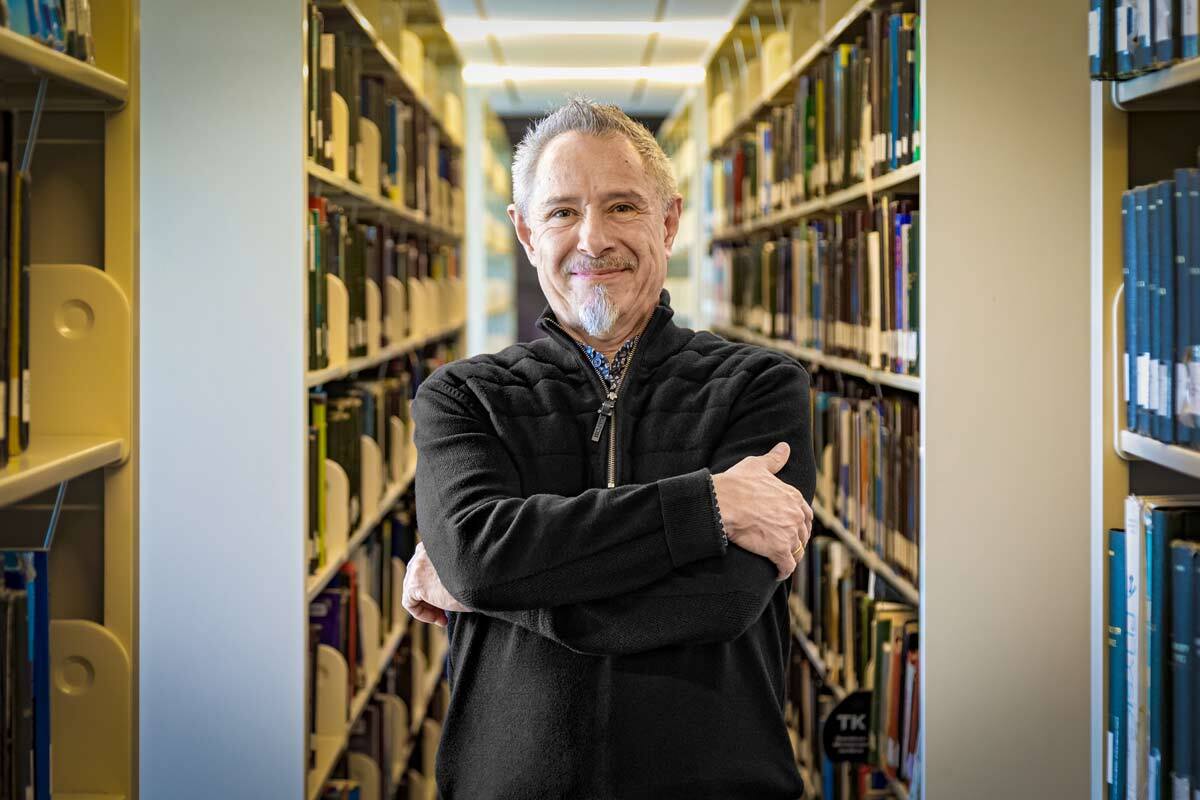

Edmundo Molina says that if something defined his path, it was mathematics. That discipline opened doors for him until it turned him into one of the leading experts in decision science: a field that combines cognitive, economic, and mathematical sciences to study how individuals and organizations choose what to do when facing different scenarios.

In addition to chairing the Society for Decision Making Under Deep Uncertainty (DMDU), made up of hundreds of scientists who apply mathematical models to issues such as natural resources, epidemiology, economic development, and security, he leads the Decision Science Research Center at the School of Government and Public Transformation at Tecnológico de Monterrey.

After studying civil engineering, working as an information systems consultant, and spending time at the Bank of Mexico, he received a scholarship to pursue a master’s degree in mathematical modeling applied to public policy in the Netherlands. But the real turning point came at the RAND School of Public Policy, where he worked with Steven Popper and Rob Lampert, pioneers in simulating large-scale social systems.

“Creating evidence where it seems like none exists?” I ask at the beginning. “Exactly. Complexity or uncertainty shouldn’t prevent us from generating evidence that helps us figure out what to do, even with all the volatility that exists,” he replies enthusiastically.

How do you study decision-making through mathematics?

At the Center we specialize in high-uncertainty contexts. We run neurocognitive experiments in which we present people with problems with different levels of ambiguity and study how they process information, what they pay attention to when making a decision, and how their performance varies.

We want to understand how a simulation model can improve that process to generate policy recommendations that are sustainable and adaptable when the context changes or new information appears.

What conclusions have you drawn?

The more ambiguity there is, the worse our decisions tend to be. Uncertainty confuses and paralyzes us. In contrast, when we have complete information, our performance improves. Additionally, we have observed that when people use decision-support tools, they make better choices.

How do your models help with climate decision-making?

We develop mathematical modules and a global platform to understand how countries can decarbonize while considering their economic development. We design a climate plan and then subject it to hundreds of thousands, or even millions, of possible scenarios. That database is analyzed through machine-learning algorithms.

With that evidence, we can determine whether it is beneficial for Mexico to decarbonize under certain circumstances, as it will generate jobs and social well-being, or which strategy works best in each context. We’ve worked in Argentina, Costa Rica, Chile, Mexico, the United States, Croatia, Georgia, and Uganda. We’ve seen a massive range of circumstances that determine what benefits each country. Now we’re trying to identify which climate decisions work across contexts.

And have you found any universally good measure?

Yes: reducing meat consumption. It has a powerful impact on forest conservation, improves health by lowering the risk of chronic diseases, increases productivity and economic growth… and it has no cost; it even generates savings.

What do you do when you’re not creating mathematical models?

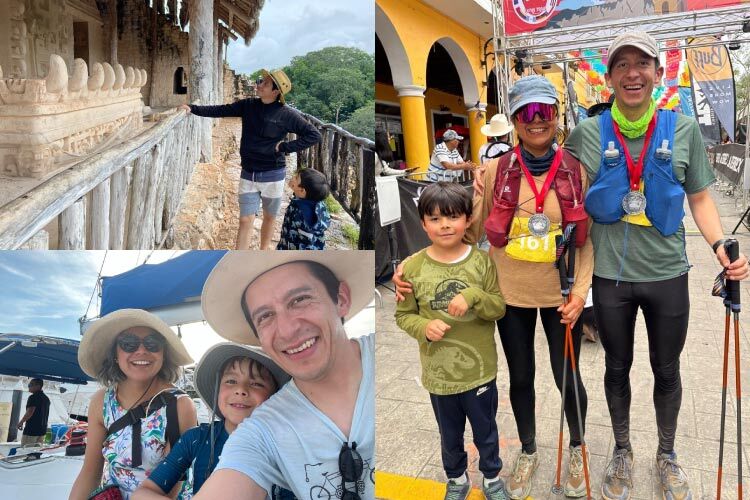

I enjoy running, especially ultratrails. Every year, I run a mountain race in Tlatlauquitepec, Puebla, my father’s hometown. I also enjoy theater, classical or jazz concerts, and cooking with my family. In September, we make chiles en nogada; at Christmas, turkey and cannolis—we spend all day making that dessert. And traveling, I love taking road trips across Mexico, which is fascinating for its diversity.

Is there something you’d like to do that your career has held back?

My wife and I are building a small hotel in my father’s town. At some point, I’d like to dedicate myself to that: moving from a fast-paced life to a calmer one, in the mountains, surrounded by greenery and rivers. It would be a completely different challenge and a way to make people happy. That attracts me a lot—sharing what you have.

Who do you share your time with?

With my seven-year-old son, who takes up all the time I have left. And with my wife, who is also a scientist: she uses mathematical models to study how climate change affects ecosystems and how we can adapt to conserve plant species, animals, or crops.

Is she an engineer too?

No, she’s a biologist. And the question makes me laugh because there were so few women in my department; I took French to meet more people… and that’s where I met her.

How did your interest in applying computational analysis to climate problems begin?

My undergraduate thesis was a financial assessment of harnessing ocean currents. I’ve been passionate about renewable energy ever since. Back then, it was almost a dream to imagine a carbon-neutral world. In my PhD I specialized in climate assessment and questions such as what the equivalent carbon price should be across regions or what it means to accelerate echnological transition in terms of time and economic impact.

In a Nature article you say that accelerating climate action requires using decision-support tools in innovative ways. How do you see future scenarios?

We have the technologies and mechanisms to solve many climate-change problems. Today it’s no longer a matter of technical capacity but of social decision: whether we want to do it. That doesn’t mean we won’t pay the costs of warming, which are already here and will persist for five more decades. What concerns me most is the widespread feeling of uncertainty.

Traveling has allowed me to see something: when there’s a lot of uncertainty, it’s tempting to let someone else solve our problems. That brings comfort, but it’s misleading: offloading responsibility means giving up freedom. That temptation can spark paternalistic impulses—sacrificing a bit of freedom in exchange for more certainty or material security. But on the other side is freedom without equity. Our generation is living that debate intensely.

Given so much uncertainty—pandemic, climate effects, technological transformations—what can Decision Science contribute?

It can provide rigorous evidence so people can make better decisions. Making decisions in a highly ambiguous environment, without information, is terrible. Between withholding information or sharing it—as happened during the pandemic—for me it should always be shared: transparency creates agency.

At times when it’s tempting to let others solve our problems, we can fall into the trap and lose freedom. And that agency is exactly what we most need to navigate increasingly uncertain and ambiguous contexts.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx