While it’s often said that someone can be “fat but fit,” new research from Mexico suggests that this might be the exception rather than the rule.

The review published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, titled Clinical Heterogeneity and Transitions of Obesity, compiles data from more than 20,000 Mexicans living with obesity and shows that it is very rare for a patient not to have any associated health conditions—especially when considering physical symptoms, mobility limitations, and mental health factors.

“This paper has two main takeaways: it’s rare to find someone with obesity who doesn’t have any disease, and the more conditions you look for, the rarer that becomes. Plus, it’s strongly associated with age,” explains Adrián Soto Mota, an internal medicine specialist, professor at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences, based at the Mexico City campus, and a member of TecSalud system.

In April, Soto was selected by the American Society for Nutrition (ASN) Foundation to receive the Peter J. Reeds Early Career Investigator Award, which recognizes outstanding research in macronutrient metabolism.

The study analyzed data collected over 15 years from the National Health and Nutrition Survey, (ENSANUT) focusing on adults between the ages of 20 and 100. The most common condition among those with obesity was dyslipidemia—any abnormal level of lipids in the blood, such as cholesterol or triglycerides, which can lead to cardiovascular and neurological issues.

Being Number One in Childhood Obesity

Soto Mota, the lead researcher, points out that Mexico’s primary issue lies in its high childhood obesity rates. According to the country’s own Ministry of Health (Ssa), Mexico currently ranks first in the world for childhood obesity.

In the past, obesity-related conditions became evident around the age of 60,” he says. “But if a child has obesity starting at age 10, it’s very likely that related diseases will begin to appear as early as age 30.

“There are people who seem healthy simply because they haven’t been to the doctor, or because nothing hurts yet. If the only two conditions you’re screening for are diabetes and hypertension, then sure, sometimes they don’t have those—but they likely have something else,” Soto Mota adds.

Obesity Is Not One-Size-Fits-All

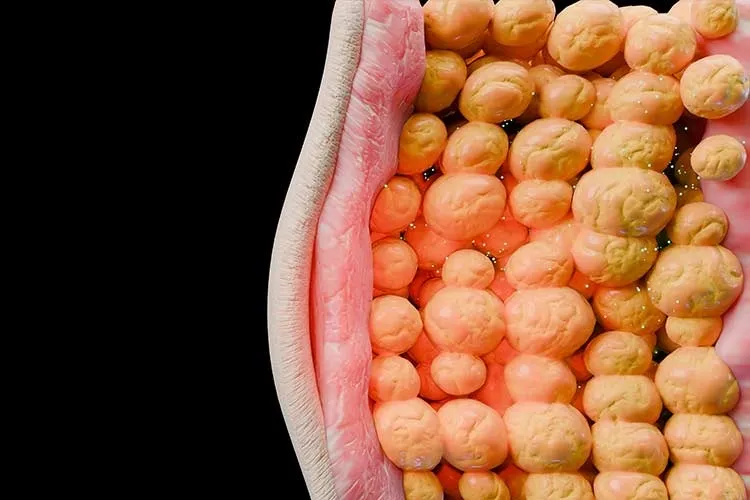

“These days, there’s a consensus on dividing obesity into two types: clinical obesity, which already presents with disease, and preclinical obesity, also known as metabolically healthy obesity, where nothing seems wrong—yet,” says the specialist.

That’s why this study uses the Edmonton Obesity Staging System, a scale developed to acknowledge that not all people with obesity are in the same state of health. The system accounts for medical, psychological, and mobility factors.

The study also used Body Mass Index (BMI), though Soto Mota notes that it has its flaws. One person might have a high BMI simply due to being broad or muscular, while another might have a lower BMI but weakened bones from osteoporosis.

Soto Mota argues that every person, regardless of weight, deserves to be treated with dignity and respect. That said, he often compares weight management to saving for retirement.

“One thing I often tell my patients is: you’re 30, you have obesity, but no current conditions—that’s great. But your bones at 60 will definitely thank you for not carrying that extra weight all those years,” he says.

So for young people living with obesity and no apparent disease, the recommendation is to try to lose weight—because statistically, sooner or later, one or more related conditions will likely emerge.

However, experts like Carolina Solís-Herrera have emphasized that tackling obesity on an individual level is not just about “willpower.” It requires a comprehensive approach that includes pillars such as nutritional education, medical support, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and physical activity—all of which often depend on public policy decisions to be truly accessible.

The Bigger Picture for Public Health

Another key point of the article, published in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, is Mexico’s shifting demographic profile. In past decades, children made up the largest share of the population. Today, that group has been replaced by young adults.

“And in this context, we hadn’t really analyzed how other obesity-related conditions change over time,” Soto Mota says.

The professor urges authorities to pay attention to the findings from this national health survey—because more and more people will need medical care at younger ages.

“What used to be needed at age 60 will now be needed earlier, and by a larger number of people. We have a lot of young adults who grew up with obesity. We’re going to start seeing chronic disease at younger ages,” he warns.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx