Pablo Kuri Morales is a medical doctor and epidemiologist. He was a public official for more than 30 years, using his knowledge to strengthen the public health system in Mexico and to respond efficiently to different emergencies.

Kuri Morales was the general director of the National Center for Epidemiological Surveillance and Disease Control at the Ministry of Health, and the general director of Epidemiology, as well as the deputy minister of Prevention and Health Promotion of the Ministry of Health.

In 2009, he was part of a group of experts that coordinated the response to the AH1N1 influenza pandemic. He was Mexico’s representative in the G7 Global Health Security Initiative for about 15 years and has responded to threats such as anthrax, dengue fever, cholera, and other infectious diseases.

Now, Kuri Morales now works as director of the Tec de Monterrey’s oriGen project, which seeks to sequence the genome of 100,000 Mexicans in 17 cities across the country.

In an interview with TecScience, he recalls the most important moments of his career and reflects on the importance of epidemiology and how it can help us prevent future pandemics.

“There are four factors that could lower the risk of deaths nationwide if we practiced them: eating healthily, exercising, not smoking, and wearing seat belts.”

Pablo Kuri: epidemiology matters

What is epidemiology and why is it important?

They say that epidemiology is the essence of prevention. The classic definition says that it is the study of risk factors and determinants of health and disease in populations.

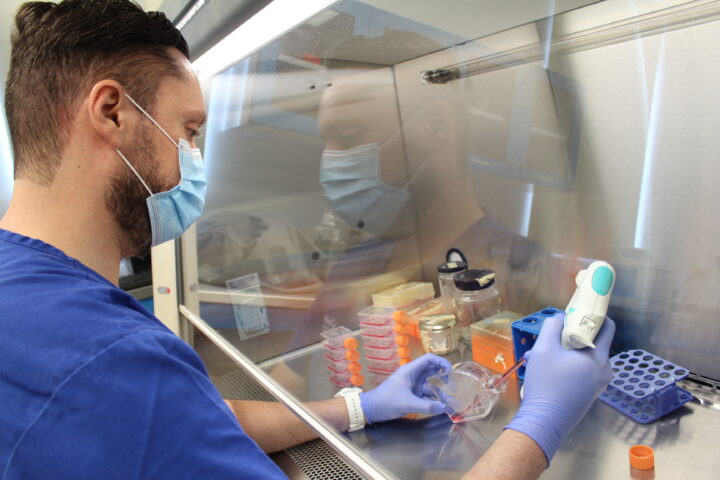

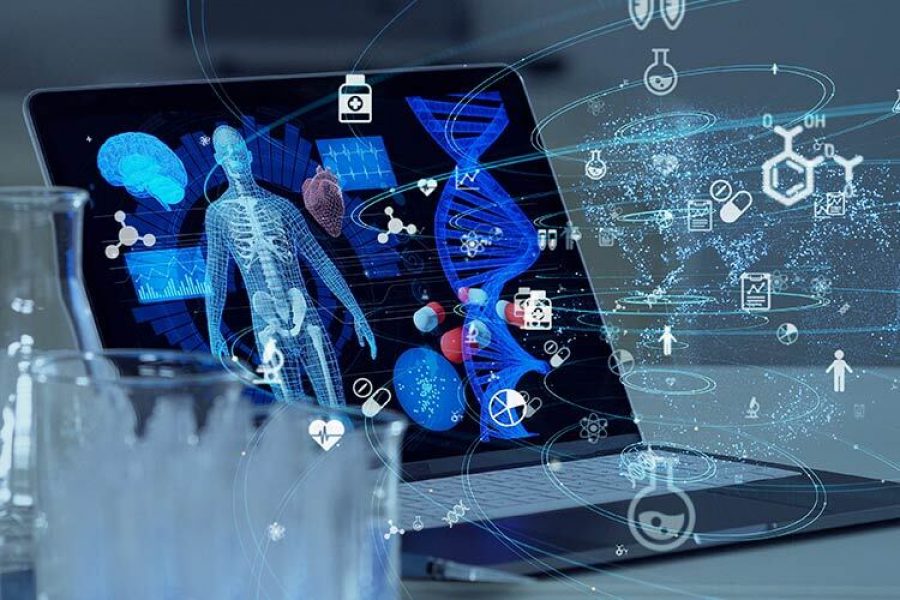

Unlike clinical medicine, where the classic tool is the stethoscope, and basic science, where it is the microscope, the tool of epidemiology is statistics and, of course, now computers and everything you use to analyze information in very large quantities, because we’re talking about populations, and being able to reach conclusions about them. Decisions made in epidemiology contribute to public health policy decisions.

For example, the decision to include or not to include a vaccine should be based on epidemiological information regarding the benefits or risks to the population. Today, global decisions regarding COVID-19 are based on epidemiological information.

What are you currently focusing on?

One of the things I’m working on is at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education, leading an extraordinary project called the oriGen project. It’s epidemiology because we are going to recruit 100,000 Mexicans to carry out population-based analyses, not one by one, but in groups, in order to later reach what is called precision medicine. It will allow us to know, for example, if we have certain genetic characteristics and therefore what medication or dosage is best suited to our genetic condition. That’s the part that takes up most of my time as an epidemiologist, and also the part I’m most passionate about.

In addition, as an epidemiologist, I’m an advisor to some companies responding to the COVID-19 pandemic, and I provide guidance based on my prior knowledge and experience as an epidemiologist and evidence-based public policy maker.

Human resources training and scientific research are things I have never and will never give up on.

What events are the highlights of your career as an epidemiologist?

For 30 years, I was a public official. In those 30 years, I witnessed things that I believe are milestones in public health. First: I was assigned the task of creating the epidemiological surveillance system for addictions in 1990 when they were not the problem they are today.

In 1995, I modernized the epidemiological surveillance system in general, and I also participated in the introduction of several vaccines to the vaccination schedule such as pneumococcus, pneumonia, and later the human papillomavirus vaccine.

As a team, we developed the epidemiological emergencies and disasters program, which I also loved because it involved a lot of fieldwork. I don’t know if they still do it, but people from the health department used to control epidemic outbreaks during natural disasters.

When the 911 attacks occurred on September 11, there were anthrax and bioterrorism warnings. I had the privilege of representing our country for 15 years in a group that was created as a United States initiative, called the G7, which gathered together the most powerful countries: Germany, the United States, Japan, France, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Italy, and they added Mexico, probably for geopolitical reasons. In 2003, one of the decisions was to prepare for an influenza pandemic, and it finally came in 2009.

I’ve led teams to prevent dengue and cholera outbreaks, such as the 2013 outbreak in the state of Hidalgo, where we focused on mitigating and stopping that outbreak.

So in the last decade, I’ve had experience with everything from chronic to infectious diseases, to being the head professor for clinical epidemiology residencies.

Covid-19 pandemic

From an epidemiological perspective, what would you have done to tackle the pandemic, or would you have acted in the same way?

I think it’s a very complicated question and this is why. To begin with, COVID-19 is a 100% new disease whose behavior was unknown at first. What I do believe is that decisions on public health must be made based on scientific evidence and if the evidence changes, then we have to change the decisions. For example, at the beginning of the pandemic, even the World Health Organization (WHO) said that the use of face masks wasn’t very useful, but later there was enough evidence to show that the use of face masks was, and still is, one of the most effective measures before vaccination to prevent the transmission of COVID-19.

What can we do to prevent a future pandemic?

The concept of health is very important for pandemics. We cannot think that animal and human health are unrelated. In fact, they’re very closely related and must be addressed in a parallel, joint, and coordinated manner. Most of the infectious diseases of humans first affected animals and then passed between species and reached us, and we have also infected some animals.

The concept of health implies that epidemiological surveillance isn’t exclusive to human populations, but also to animal populations.

Let me tell you that the probability of a new pandemic is 1, this means that there will be a new pandemic for sure. Where will it come from? We don’t know. When? We don’t know. But there’s going to be another pandemic, that’s for sure.

We are responsible

Knowing this, how can we prevent attacks on wild animals?

Look, the worst enemy of health and public policy is ignorance and stigmatization. With the so-called chicken flu, nobody wanted to eat chicken anymore, but what people don’t know is that when there’s an outbreak of influenza in chickens, the poor chickens get in very bad condition [physically], so it’s impossible to eat them. What’s more, it’s not transmitted by eating chicken meat, it’s transmitted by chicken secretions, either their saliva or urine.

Or bats, for example. They were already killing all the bats because of some cases of rabies transmitted by bats in Oaxaca. This is a mistake. What should be done is to avoid interaction between bats and children; killing a colony of bats is bad for the ecology of the region.

We must not forget that despite all that we humans have done to destroy the environment, there is still a balance between animals, plants, water, the atmosphere, the environment, and us.

Stigmatizing animals because some diseases come from them is not right, because it’s not their fault. It’s our fault for living so close to them when we should not, or for overpopulating.

What would you like to tell people based on your experience as an epidemiologist?

We’re all responsible for self-care, no matter how much epidemiology and public policy there is, we have to make personal, family, and social group decisions to avoid certain risks that are absolutely unnecessary and known, since we cannot avoid fatalities completely.

The perception of risk is very important. During COVID-19, when the vaccines came out, people even fought over them because the risk was immediate; if you didn’t get the COVID-19 vaccine, you could die the next week or the next month, so people got vaccinated because the risk was immediate. However, if you advise someone not to smoke because they might get lung cancer 20 or 30 years from now, they’ll say, “Oh well, that’s a long way off. I can keep smoking,” because the risk isn’t immediate.

Today, thanks to epidemiology, we know for sure that there are many factors that affect populations and many others that could help them. There are four factors that could lower the risk of deaths nationwide if we practiced them: eating healthily, exercising, not smoking, and wearing seat belts.