Paola Ricaurte has spent her life circling the globe, absorbing customs from one country and another, from here and there, learning and enriching herself through a blend of cultures. “What’s beautiful about having had experiences in so many places is that you start to take something from each one until you become a mix of many things,” she says with a wide smile, after walking through her life story—a journey filled with countries, experiences, her two children, and favorite foods.

Her parents were Ecuadorian, but she was born in Bogotá, Colombia. Later, she attended high school in Barcelona, and then moved to Russia—a country that left a deep impression on her thanks to “its music, ballet, composers, and literature.” That’s where she studied journalism, though she never worked in that field.

“I’ve always loved math and technology. And early on, I got involved in activist movements that were tied to both.”

Today, Ricaurte is a professor and researcher in the Department of Media and Digital Culture at the School of Humanities and Education at Tecnológico de Monterrey. She also coordinates the Feminist AI Research Network (FAIR), which seeks to create and sustain a feminist research agenda designed by and for women.

She has built most of her academic and activist career in Mexico, where she now lives and became a naturalized citizen. “And now I can’t live without chile,” she jokes. Throughout the interview, her sense of humor is constant, as are her big smiles—and her fiery passion for human rights in the digital space.

Ricaurte is the author of the Decolonial AI Manifesto and co-founder of Tierra Común, an academic initiative for the decolonization of data. She’s widely recognized as one of Latin America’s leading voices pushing back against hegemonic technological systems that entrench global inequalities.

A Personal Encounter with Algorithmic Bias

How are the biases in AI—those stereotypes you’re fighting against—actually built?

The AI we use today—especially the commercial kind—is driven by market logic and profit. It’s extractivist, patriarchal, racist, and colonial. The vast amount of data it relies on is mostly scraped from the internet, which tends to reflect dominant, hegemonic knowledge systems. So what you find online isn’t really a true mirror of who we are as a global society.

When models are trained on that kind of data, they produce outputs that exclude us—women, our languages, and aspects of life that matter deeply to us. They tend to represent a narrow group of people considered the default: white men with a certain socioeconomic status and education. The results are riddled with all kinds of bias.

Experiencing this firsthand was a turning point in Ricaurte’s career. In 2018, while she was at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, she had already developed a critical perspective on the need to decolonize and depatriarchalize tech. But until then, she hadn’t personally felt the real-life consequences of the inequality embedded in those systems. That experience pushed her to investigate, alongside others from the Global South, where these systems come from, whose interests they serve, and how they appropriate knowledge. She began to specialize in analyzing how social constructs like racism and sexism are reproduced through technology—and how to resist them through knowledge.

How do these intersecting biases impact real people’s lives?

The consequences can be serious. When AI is used in public services that don’t reflect the realities of anyone outside the white-male-default, it can limit access to healthcare, credit, or education. But in other contexts, the harm runs even deeper.

For example, when police forces use AI tools to predict who might commit a crime, it often ends up criminalizing young people. Or when teen pregnancy prevention systems are used to police women’s bodies. Sadly, cases like these have already occurred in countries like Argentina and Brazil.

Of Love, Borders, and the Struggle for Just AI

After bouncing from country to country, how did you end up in Mexico?

Like a lot of people—because of love. I met a Mexican in Russia, and that’s what brought me here. I found a job at Tec, and then I stayed. I married a Cuban, but my two children were born in the US. So between the four of us, we have I-don’t-know-how-many passports and nationalities. We’re a multicultural family. My kids, for example, even though they grew up in Mexico, are familiar with Ecuadorian and Cuban terms and navigate different cultures pretty easily.

Diversity is one of our greatest strengths as human beings—the many ways of being, of thinking, of existing in the world, the variety of languages…

How do we push back against the biases built into hegemonic AI—biases so out of step with the multicultural identity you’re proud of?

The problem is that AI bias stems from multiple layers: from the data itself, from the models, from how they’re deployed. That makes it incredibly hard to trace and fix. That’s why we, as a society, must demand transparency—especially when these systems are used by governments. We need technological governance. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of tech systems is essential when they impact our lives directly.

As Ricaurte sees it, technologies can reproduce systemic inequalities—not just within countries but also between them: “between the nations building AI and those that aren’t.” When she joined GPAI in 2020, Mexico was the only Global South country at the table. Later, Brazil and Argentina joined.

“When you realize how underrepresented we are in these international conversations, it becomes clear why the agenda is always shaped by the interests of the countries that are building and controlling the technologies. And, generally speaking, it’s the United States calling the shots.”

The US is the dominant force in tech—but what about other regions? Where does Latin America stand in the geopolitics of AI?

Latin American AI policies vary widely by country, but they lack a shared, regional, sovereign vision.

Having more control over our data and tech could help fuel regional development. These are not issues a single country can fix alone. And we also need to consider that the region’s survival is deeply tied to the exploitation of natural resources linked to tech development. One of my existential worries is that we’re not having serious conversations about this—about lithium, about water, and the sustainability of life in the near future.

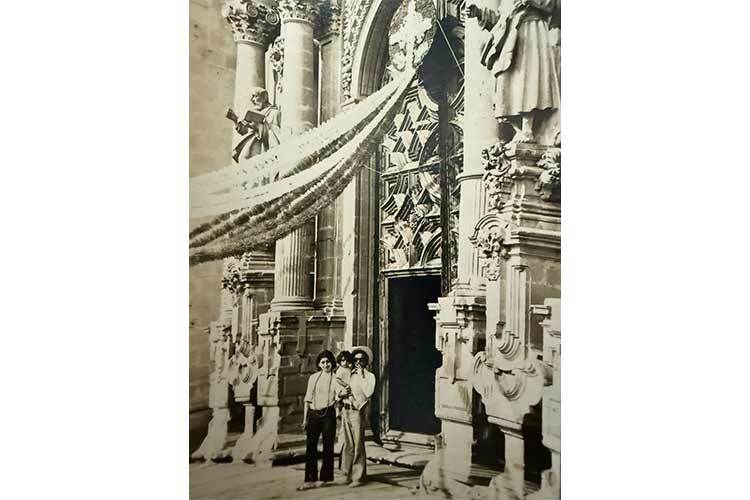

(Photo: Courtesy)

A Latin American Vision for Fair AI

Ever since she was a teenager, Paola has carried a rebellious streak. “I was involved in collectives defending digital rights, privacy, and fighting state surveillance. I came from the free software movement, the open culture movement, the open knowledge movement. And then the feminist wave hit me too,” she says, pointing to her laptop covered in stickers: clenched fists, “Women’s Rights are Human Rights”, “Hack Your Struggle”, “Datagender”, “There’s No Tech Without People”…

Are there real alternatives to AI systems that just replicate the world’s inequalities?

I have a lot of hope in Latin America. There are grassroots groups and initiatives here that are not just theorizing but actually building technologies that aren’t rooted in colonial, patriarchal, or capitalist logics. These are technologies designed to solve real problems for real people in our region.

One project in Mexico worked with the Yaqui tribe to develop a tool that helps monitor their territory—especially water resources—so they can make better decisions around community water governance. Their water situation is critical.

These are technologies built for us, in our languages, addressing our needs.

Paola Ricaurte speaks Spanish and English, and she also understands Portuguese, Italian, and French—skills that have helped her explore the world. Her personality radiates optimism, and talking with her leaves you with a renewed sense of hope in the world, in humanity.

One of her favorite parts of traveling, she says, is trying traditional breakfasts. “I wake up super early, so breakfast is my favorite meal. I love Mexican chilaquiles, I’m obsessed with arepas and Colombian soups, I love that in Brazil they give you a ton of cheese bread, and in Costa Rica, beans with rice, plantains, eggs, and cheese,” she says, laughing nonstop.

Paola Ricaurte speaks Spanish and English, and also understands Portuguese, Italian, and French—skills that have allowed her to explore the world. One of her favorite parts of traveling is trying traditional breakfasts. (Photos: Courtesy)

What do you imagine the future of AI looks like?

A future that includes us. But to get there, we have to do the work—think as a society about what kinds of technologies we want and deserve. We also need political will to support tech development that’s better aligned with our contexts, our populations, and our languages.

One of my dreams is to help Indigenous communities develop their own datasets, licenses, and technologies so they can achieve sovereignty, preserve their cultures and languages, and protect their ancestral knowledge.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx