By Ana Sofía Leyva Márquez | CIENCIA AMATEUR

Reviewing author Jorge Eugenio Valdez García

Every year, millions of people lose their vision to diseases that could have been detected early. This is especially troubling given that the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1 billion cases of blindness are preventable [1].

One of the leading causes of vision loss is diabetic retinopathy, a condition directly associated with impaired visual acuity. A study found that most patients who arrive with severe vision impairment already present advanced-stage proliferative retinopathy—often associated with poor glucose control and more than a decade of living with diabetes [2].

The disease also affects vision by contributing to dry eye and reduced corneal sensitivity [3].

This is the backdrop against which the IDX-DR AI algorithm emerged—the first autonomous system approved by the FDA to detect diabetic retinopathy without a physician present. It analyzes retinal images taken in primary care and, within seconds, determines whether the patient requires a referral to an ophthalmologist [4].

It’s a clear example of how smart technology can support medical professionals by acting, making decisions, and preventing issues.

What is diabetic retinopathy?

Diabetic retinopathy is the most common cause of preventable blindness in adults. It is a diabetes-related complication in which the blood vessels in the retina become progressively damaged. The main challenge is its silent nature: by the time symptoms appear, the damage is often irreversible—making early diagnosis essential.

According to the WHO, nearly 1 billion people worldwide were living with preventable visual impairment in 2019. In most cases, the problem isn’t a lack of treatment but rather a diagnosis.

In rural or low-resource regions—where eye-care specialists are scarce—detecting these diseases before it’s too late is especially difficult.

In Mexico, a 2021 study by Maeda-Gutiérrez et al. found that 27.5% of people with type 2 diabetes had diabetic retinopathy—an alarming figure in a country with one of the highest diabetes rates in Latin America [1,5].

AI steps in

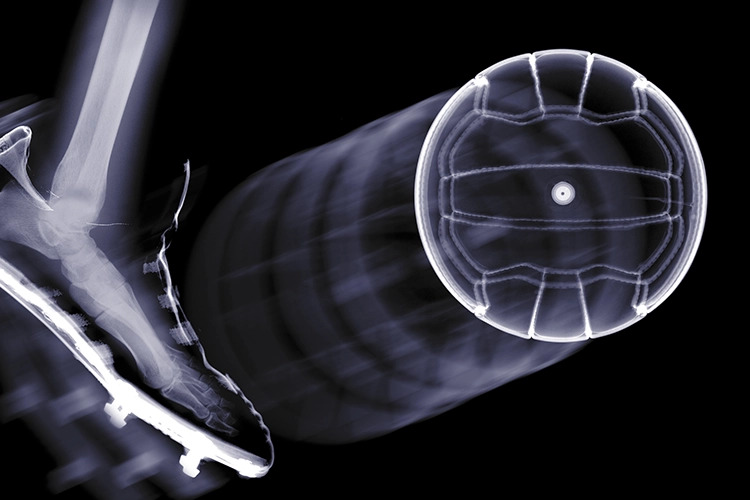

Developed by Digital Diagnostics in 2018, IDX-DR is an autonomous system that combines a computer, a special camera, and diagnostic software. It analyzes retinal images and determines whether diabetic retinopathy is present. In other words, it functions as a “miniature ophthalmologist,” delivering a referral decision in seconds. Its accuracy comes from machine learning: it was trained on thousands of labeled medical images, enabling it to recognize disease indicators with precision.

It’s also easy to use: the system gives only two outcomes—“refer to a specialist” or “continue monitoring”—which allows trained non-specialist staff to operate it without an ophthalmologist present [4].

Smart technology as an assistant

Artificial intelligence isn’t meant to replace physicians, but to make their work more efficient by providing fast, accurate, and accessible data. IDX-DR serves as a filter, identifying retinal damage before symptoms appear and determining who needs urgent attention. This enables timely treatment while reducing specialists’ workloads, since trained personnel can perform the initial screening.

And this is only the beginning. Algorithms are already capable of detecting glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration. They can also tailor treatments by analyzing large medical datasets to predict which therapies will work best for each patient, minimizing trial and error [4,8].

In surgery, AI enhances precision and speeds up procedures such as cataract removal, reducing complications and improving visual outcomes. It is also used in virtual-reality systems to train physicians without risk to real patients.

AI is also expanding tele-ophthalmology: using portable phone-connected cameras that capture retinal images to remotely analyze them for signs of diabetic retinopathy and other diseases, thereby bringing eye care to rural and underserved areas [4,6,7].

Will AI help us see better?

What sounds like science fiction is already on the horizon: technologies that will let people take a photo with their phone, upload it to an app, and receive an eye-health assessment. This could enable rapid, at-home diagnosis of conditions such as diabetic retinopathy, as well as remote follow-up—saving time for both patients and healthcare systems [9].

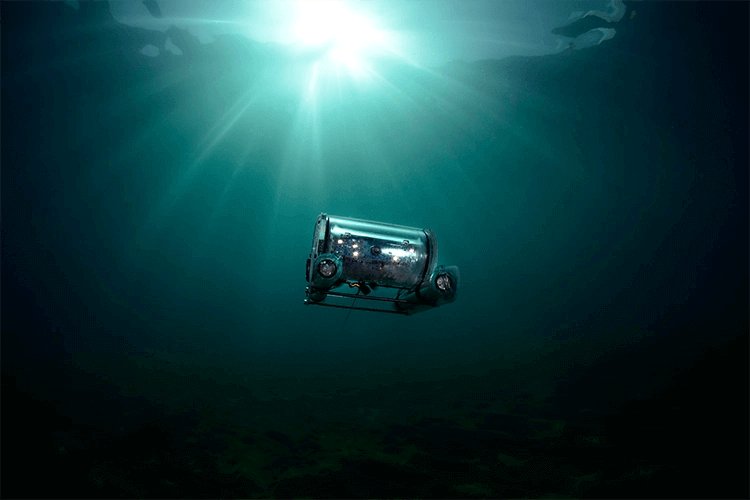

Another emerging innovation is smart contact lenses (SCLs), capable of continuous, non-invasive, real-time ocular monitoring. These devices analyze tear fluid to track intraocular pressure, glucose levels, or early signs of glaucoma and diabetic retinopathy—and in some prototypes, even deliver medication wirelessly.

Though still under development, they may soon help diagnose and prevent complications through constant monitoring [10].

Across the board, these AI tools could empower patients to take a more active role in their diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring—promoting autonomy and self-care for eye health.

Artificial intelligence is reshaping the future of ophthalmology. With tools like IDX-DR, we no longer have to wait for symptoms to act. Early detection—and even prevention of blindness—is now possible from a general clinic, a rural community, or even someone’s home.

AI isn’t here to replace specialists, but to give them more time and better tools to protect everyone’s vision. The future looks promising—and thanks to AI, it may also look clearer.

References

- Noncommunicable Diseases, Rehabilitation and Disability (NCD). World report on vision. Published 8 de octubre de 2019.

- Valdez-Garcia, J. (2005). Riesgo de pérdida visual en pacientes con retinopatía diabética.

- Carlos Guerrero Acosta, J., E Ruiz Lozano, R., M Gonzalez Madrigal, P., & Valdez Garcia, J. (2024). From Retina to Cornea: Quantifying the Impact of Diabetic Retinopathy on Dry Eye Disease and Corneal Sensitivity. IOVS Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 65, 2949.

- Abràmoff, M.D., Lavin, P.T., Birch, M. et al. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. npj Digital Med 1, 39 (2018).

- Maeda-Gutiérrez V, Galván-Tejada CE, Cruz M, Galván-Tejada JI, Gamboa-Rosales H, García-Hernández A, Luna-García H, Gonzalez-Curiel I, Martínez-Acuña M. Risk-Profile and Feature Selection Comparison in Diabetic Retinopathy. J Pers Med. 2021 Dec 8;11(12):1327.

- López Cabrera, M., & Valdéz García, J. E. (2019). Virtual reality in residents’ training. AES Annals Of Eye Science, 4.

- Olawade, D. B., Weerasinghe, K., Mathugamage, M. D. D. E., Odetayo, A., Aderinto, N., Teke, J., & Boussios, S. (2025). Enhancing Ophthalmic Diagnosis and Treatment with Artificial Intelligence. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 61(3), 433.

- Grzybowski, A., Peeters, F., Barão, R. C., Brona, P., Rommes, S., Krzywicki, T., Stalmans, I., & Jacob, J. (2025). Evaluating the efficacy of AI systems in diabetic retinopathy detection: A comparative analysis of Mona DR and IDx-DR. Acta ophthalmologica, 103(4), 388–395.

- Swaminathan, U., & Daigavane, S. (2024). Unveiling the Potential: A Comprehensive Review of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Ophthalmology and Future Prospects. Cureus, 16(6), e61826.

- Kazanskiy, N. L., Khonina, S. N., & Butt, M. A. (2023). Smart Contact Lenses-A Step towards Non-Invasive Continuous Eye Health Monitoring. Biosensors, 13(10), 933.

Author

Ana Sofía Leyva Márquez is a sixth-year medical student at Tecnológico de Monterrey. Originally from Chihuahua, she has developed an interest in ophthalmology research and the application of artificial intelligence in the field of healthcare. She currently collaborates on clinical and science communication projects focused on technological innovation in medicine.

Reviewer

This article was supervised by Jorge Eugenio Valdez García, an ophthalmologist specializing in the cornea and anterior segment. In addition to contributing as an author of science communication articles for TecScience, he serves as a research professor at Tecnológico de Monterrey and leads educational and medical innovation projects.