By Francisco Javier Serrano Bosquet, Lina María Carreño Correa and Emanuele Giorgi

Every day, new technological and scientific discoveries, products, and services integrate into our daily lives, promising a fairer, freer, and safer future if we make social, political, and economic adjustments. The Enlightenment or modern dream could—seemingly—come true.

Nicolas de Condorcet—a French politician, philosopher, and scientist of the 18th century—summarized the Enlightenment’s motto in these terms: “Our hope for the future of the human species can be reduced to these three questions: the destruction of inequality between nations, the progress of equality within a single nation, and, finally, the perfection of humankind” (Condorcet 1794/1980).

In other words, eliminating inequality, advancing equality, and improving the human condition.

In this sense, the “hard sciences” and the technological development they have facilitated seem to have done their part. However, the promises of modernity and the so-called ‘hypermodernity’ or ‘liquid modernity’ have not been fulfilled. On the contrary.

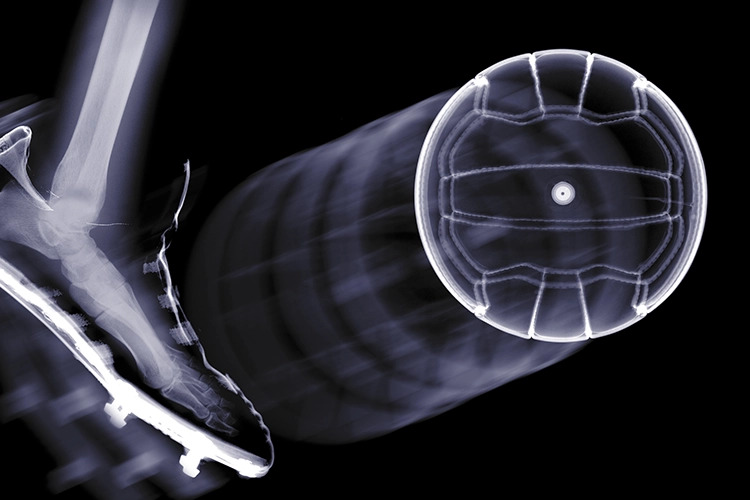

Technological Nightmare

Technology has created new inequalities and vulnerabilities. Just as between World War I and World War II, the dream of reason has become a nightmare for a large part of the population. Despite advances, the number of vulnerable individuals and communities remains very high today and has even increased in recent years in various regions of the world (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, 2022).

For example, in 2021, 50 million people lived in conditions of modern slavery, an increase of 10 million more than in 2017. This means nearly one in every 150 people in the world is in that situation (ILO; IOM; Walk Free 2022).

Additionally, we are facing a food security crisis (World Bank 2023) and increasing difficulty accessing potable water. Even in cities that seemed to have boarded the ‘train of progress,’ solutions to basic needs for their populations are elusive.

Vulnerability: The Challenge

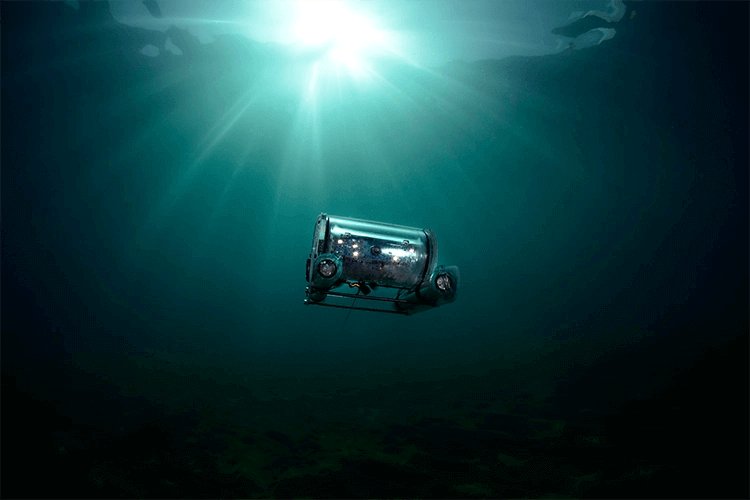

The causes of this failure are multiple. One of them is the emergence of new factors, contexts, modes, and degrees of vulnerability. In this context, technology appears as one of the main strategies for action, provided it is approached from a decidedly interdisciplinary perspective and is aware of the difficulties, risks, and complexities inherent in any process of transfer and adoption.

At the beginning of 2023, we began the action-research project “Design for the Vulnerable – Technological Challenge,” focused on improving conditions in four communities in the Mexican state of Chihuahua: Paso del Norte and Nuevas Delicias, along with two villages in the Tarahumara Sierra.

We studied the context and potential applications of technology in six main areas (mobility, gender, climate change, resource optimization, health, and local business) that had emerged in previous projects as the main relevant issues in these particular contexts. We also conducted a systematic review of the primary scientific literature to understand the role of technology in vulnerable communities.

This study allowed us to identify annual publication trends on technology and social vulnerability, the thematic areas or scientific disciplines from which these topics are analyzed, the main issues addressed, the organizations or institutions funding such research, and the types of vulnerabilities referenced, as well as the technologies being developed or implemented.

We also highlighted the degree of uncertainty surrounding these projects, as well as the need for genuine modesty and humility in designing and carrying out technology transfer and adoption processes.

Technological development can be one of the main drivers of change, but it can also be a primary creator of greater and deeper socio-environmental gaps. Hence, there is a need to be aware of the multiple impacts—both direct and indirect, desired or undesirable—that technological development can have on society.

For the team at the School of Architecture at Tec, it was important to deeply reflect before implementing any urban-architectural intervention.

Adding Social Innovation

The results from our bibliographic research are helping us better understand our study phenomenon, appreciate international trends, explore different alternatives and risks, and improve the design of our methodologies. We encourage all research groups to undertake similar activities.

We believe that these results can guide future research and development projects by using appropriate technologies to reverse observed conditions of vulnerability.

It is crucial that those defining, managing, and guiding such projects understand the importance of involving various social actors and the accompanying axiological diversity.

“Axiological diversity” is a philosophical concept referring to the coexistence of multiple value systems, principles, and beliefs within a society or community. In philosophy, “axiology” is the study of values, including what people consider good, just, ethical, or valuable.

The role of academics and researchers is crucial, but social innovations required to address many conditions of vulnerability need contributions from representatives of the industrial, governmental, and civil society sectors.

One of the main recommendations from the reviewed literature is to develop technologies and protocols that facilitate communication and decision-making in a fair, democratic, and inclusive manner. Social innovation, a plurality of voices, participatory symmetry, and, of course, technical knowledge are fundamental to the success of our transformative actions.

References

- Banco Mundial (2023), Food Security. Update. Washington,

- Condorcet (1794/1980), Bosquejo de un cuadro histórico de los progresos del espíritu humano. Madrid: Editora Nacional.

- Lente, H. van (1993), Promising Technology. The Dynamics of Expectations in Technological Developments, Twente. Universidad de Twente.

- IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, DC Roberts, M. Tignor, ES Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Prensa de la Universidad de Cambridge. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Reino Unido y Nueva York, NY, EE. UU., 3056 págs.

- OIT, IOM & Walkfree (2022). Global Estimates on Modern Slavery: Forced Labor and Forced Marriage. Genova: Walkfree

.

Note: The “Design for the Vulnerable – Technological Challenge” project is funded by the 2022 Challenge-Based Research Funding Program [grant number E021-EAAD-GI01-B-T1-E], Tecnológico de Monterrey, Monterrey, NL, Mexico.

Editor’s Note: In the referenced research, the Scoping Review methodology was used to identify and review relevant articles from 2013 to 2023 in databases such as Web of Science and Scopus, focusing on keywords related to design, indicators, and technological challenges.

Authors

Francisco Javier Serrano Bosquet. Bachelor’s and Ph.D. in Philosophy from the Complutense University of Madrid. Currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Humanistic Studies, School of Humanities and Education, Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Lina María Carreño Correa. Bachelor’s in Industrial Microbiology and Master’s in Environmental Management from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Bogotá, Colombia), Ph.D. in Environment and Development from Universidad Autónoma de Baja California (Ensenada, Baja California, Mexico). Currently a Postdoctoral Researcher at the School of Architecture, Art and Design, Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Emanuele Giorgi. Building and Architecture Engineer and Ph.D. in Civil Engineering and Architecture Education from the University of Pavia (Pavia, Lombardia, Italy). Currently Director of Research and Full Professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design, Tecnológico de Monterrey.