Southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina), whose natural habitat is Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, have traveled as far as Baja California in Mexico, the farthest north they have been seen in the Americas. This was totally unheard of until very recently, and Mexican scientists played a part in the discovery.

It was also discovered that the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico receive different ocean currents from Antarctica, where the highest warming rates on the planet have been recorded due to climate change. The melting ice is releasing millions of microorganisms into the sea and we don’t know what the effects will be.

Mexico is geographically and conceptually very far from Antarctica (more than 13,000 kilometers away), but many things are happening there that concern us.

The Mexican Agency for Antarctic Studies (AMEA) was created to consolidate our country’s presence on the continent. We tell you why Mexicans need to be there.

Antarctica can belong to the whole world

The only way to enter the Antarctic governance ecosystem is by doing science there. This is the only continent of peace that belongs to all countries that want to be a part of it, as long as they adhere to the Antarctic Treaty, an initiative from 12 countries that has 54 signatories today.

Mexico is not yet a member, but the AMEA (created in 2018) is pushing for the country to formally join so that interested scientists can study on the continent.

It brings together almost 200 Mexicans (living in the country and abroad) who are specialists in microbiology, geology, geography, astrophysics, social sciences, physics, and diplomacy. There are even business owners and volunteers interested in doing data science based on what’s being studied there.

AMEA’s director, Pablo Torres Lepe, who is also a full professor at Tec de Monterrey’s School of Engineering and Sciences, says that “the first Mexican conference on Antarctic science will be held at the end of October, and he hopes that consensus will be reached to make diplomatic, scientific, and economic advancement toward consolidating Mexico’s presence.”

Negotiations have already taken place between the Mexican Agency for International Development Cooperation (Amexcid) and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (SRE). One step forward has been the Mexican Academy of Sciences (AMC) becoming an official member of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) last year.

Torres Lepe estimates that by the year 2048, Mexico will have solid representation in the Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty in Argentina.

Upon signing the treaty, the country would recognize Antarctica as a world heritage site, have a say in its governance and legislation, and would be able to establish a base on the continent where Mexican researchers can go, as well as being obliged to pay a membership fee to SCAR and develop a national Antarctic science program.

Why Antarctica?

Many natural phenomena link us to that continent, even if we do not see them directly. One example is the migration of species, as is the case for southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina), which are normally found in Antarctica, but have traveled as far as Baja California, Mexico.

This finding was made through genetic studies of an individual on the Mexican Baja peninsula and was achieved thanks to the contribution of Mexican researchers.

If we want to understand the origin of the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico, how bladderwrack is formed, or climatic phenomena such as El Niño, we need to study Antarctica.

Finding out how climate change occurs there is vital since the Poles are where the highest warming rates on the planet are being recorded. Hand in hand with the melting ice, millions of encased viruses and bacteria are now being released into the sea and the atmosphere with effects we do not yet know.

The Jurassic Park of microbiologists

Antarctica is like a Jurassic Park for microbiologists because the viruses and bacteria that inhabit it have remained encased in time, subsisting for thousands of years in extreme conditions.

They are known as extremophiles because they can withstand very low temperatures, freeze-thaw cycles, few nutrients, low conductivity (when the water has very few salts), and little access to sunlight throughout the year.

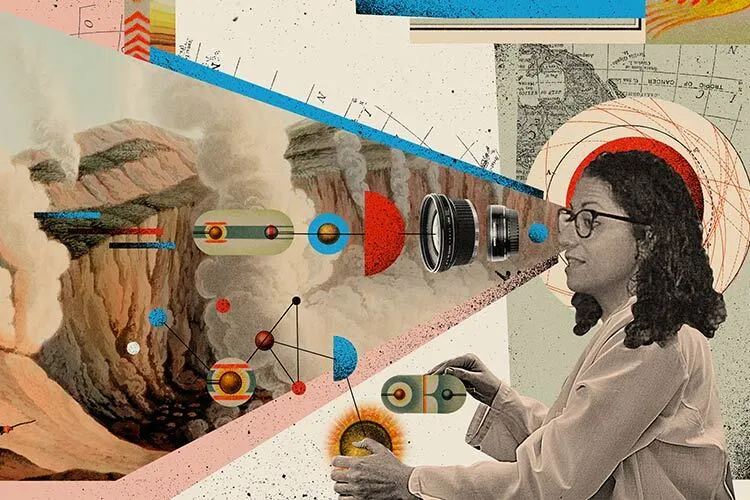

Patricia Valdespino, a project scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, California, has had the opportunity to visit the continent on three occasions to take samples of extremophilic microbial mats with groups of researchers from Uruguay, Argentina, and Chile.

“We are fascinated with them because their genomes and proteins have special adaptations to help them deal with the adverse environment. They have to figure out how to survive metabolically, which isn’t seen in microorganisms from the tropics,” she explains.

The Mexican researcher took samples in meltwater streams and extracted their complete DNA to understand their microbial diversity and metabolic potential.

“A mat has at least 500,000 species, and each one has a genome composed of 1,000 genes. This means there are 500 million genes of interest in a single sample. As a result, we have vast and complex shared libraries between countries.”

Understanding microbes

The Argentinian group Valdespino collaborated with is researching microbes that can degrade oil in the event of spills at sea, and the Uruguayans are studying antibiotic resistance genes (which will be the next health crisis) to produce new generation drugs.

The microbiologist has been studying the strategies of microorganisms to tackle environmental changes since it is unknown what effects they will have once released into the environment. However, they will surely be very important because they are the great transformers of the planet.

Microbes are responsible for red tides, primary productivity of the oceans, and methane emissions, and they can also contribute to humanity’s new biomaterials and new bioproducts for a sustainable future.