“You are what you eat” has become the central concept of a research study involving microbiota and genetics to help with the preservation of endangered animal species.

The diet of both humans and animals influences the hundreds of millions of bacteria that live in the intestine, respiratory tract, mouth, and even the surface of the skin.

Their importance extends beyond digestive matters, as they also help regulate other critical areas, such as physical and mental health and the immune system.

In the northeast of Mexico, the Desert Museum (MUDE or Museo del Desierto in Spanish), which was founded in 1999 in the city of Saltillo, Coahuila, not only preserves the past through its dinosaur fossils but also attempts to safeguard the future by serving as a refuge for endangered animals such as prairie dogs and black bears.

Researchers from Tecnológico de Monterrey and MUDE scientists have collaborated on research that focuses on the microbiota of endangered animal species and its impact on their health to contribute to their conservation in captivity and eventual release into the wild.

Analysis of the microbiota of endangered species could help us to understand how they have evolved to survive in challenging scenarios, which might guide us on how to preserve these animals.

Microbiota to prevent the extinction of endangered animal species

If the microbiota were a forest, the researchers’ task would be comparable to evaluating soil conditions, the number of trees, the health of rivers, lakes, and foliage that constitute the complete ecosystem, and then designing measures to encourage and preserve a state of balance.

By 2010, the Mexican prairie dog (Cynomys mexicanus), was classified as an endangered species by the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT), just eight years after doing so for the Black Bear (Ursus americanus) in 2002.

Rocío Chávez Santoscoy, a research professor at Tec de Monterrey’s School of Engineering and Sciences and the founder of the Genomics Core Lab, explains that their project involves analyzing the microbiota of these endangered animal species, understanding their health status, and intervening to improve their chances of survival.

Chávez’s team also includes doctor Silvia Hinojosa, a bioinformatics specialist, and biotechnology engineer Jesús Hernández, who is in charge of molecular biology and sequencing.

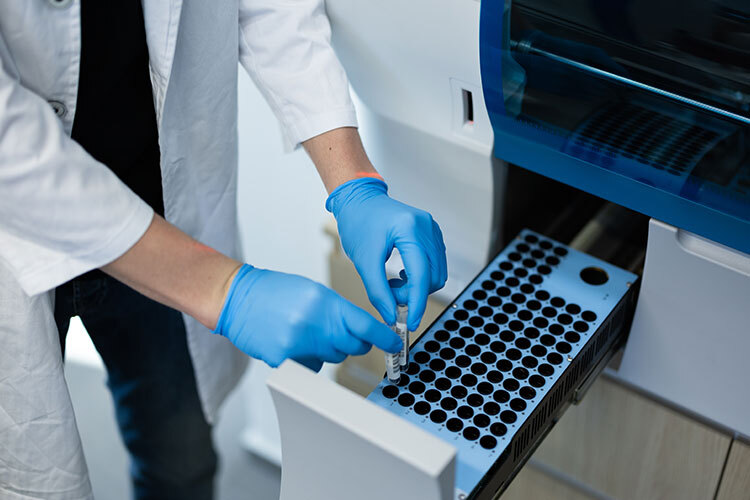

The group uses a microbiota analysis procedure that involves collecting fecal samples from bears and prairie dogs at MUDE, which are then examined in the laboratory using a DNA sequencing technique known as metagenomics.

“Through our partnership with the Desert Museum, our initial genomics project involved sequencing a gene called 16S, which allows us to identify all microorganisms present in a fecal sample,” Hinojosa explains.

This method not only identifies microorganisms found in the microbiota of a species but also detects pathogens such as viruses or parasites that may be causing damage to the animal’s health.

“We’re monitoring all parameters to ensure their health. Releasing a physically ill animal would be ineffective; you’d be essentially sending it out to die,” Hinojosa adds.

Furthermore, the researchers are investigating the application of Artificial Intelligence technology to evaluate data and build tools to forecast unfavorable circumstances such as climate change.

Wellness in animals

When it comes to bears, their arrival at the MUDE often happens due to accidents or situations that prevent them from being released immediately into the wild. As a result, they require extra care and monitoring of their health.

“The Desert Museum serves as a rehabilitation center. It depends on the age of the bear pups if they may be released again. When they are young, they imprint on humans, which is when an animal learns habits and how to seek food from humans rather than nature. As a result, if they are freed, they may assume that everyone is kind and end up being attacked or mistreated,” Hinojosa explains.

By collecting fecal samples, researchers get information that also provides guidance to the people looking after the animals at MUDE, who can then design or modify meals for species in captivity, customizing them to their requirements.

During this investigation, the researchers have discovered bacteria associated with bear health conditions like encephalitis, which may not always be visible in typical laboratory tests.

After the Tec’s examination and the care provided by MUDE experts, animals considered fit for release are set free in forests such as Sierra de Arteaga in Coahuila or in other states.

Those considered unfit for release, on the other hand, are placed within the museum’s designated areas, where they can live as peacefully as possible with a diet that closely resembles that of the wild.

The initiative has also assisted in the identification of certain bacteria associated with animal wellness that are seen in prairie dogs who live in groups. This discovery may have a favorable effect on their mood.

“We can’t say an animal is happy or content because that would be humanizing it, but we can say something is connecting them and benefits their health. We’re looking into it,” Hinojosa says.

Beyond discovering elements of animal health that are not easily observable by biochemical analysis, the initiative also aims to detect potentially harmful conditions early.

“A microbiota study allows us to predict the animal’s future health status to some extent before symptoms such as hair loss or weight loss appear, which make it more difficult to reverse their condition,” Rocío adds.

Genomic projects at Tec de Monterrey

The MUDE project is one of the first carried out by the Genomics Core Lab, a specialized research facility at Tec de Monterrey. These labs include Genomics, Preclinical Research, Data Science, and Additive Manufacturing, among others.

The research has also opened the door for additional genomic studies on reptiles, such as snakes and frogs, which have extraordinary adaptability to their environments, while also studying manta rays and other endangered marine animals, such as the mahi-mahi.

In addition, the genome analysis research focusing on giant manta rays specifically targets specimens from the Caribbean and the Gulf of California, both of which are threatened due to inadequate fishing laws.

These fields of study include collaboration between the Tec and other institutions such as the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), the Interdisciplinary Center for Marine Sciences (CICIMAR) of the National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), and the Autonomous University of Nuevo León (UANL).

“We also get samples from countries like Ecuador and Uruguay. Our goal is to strengthen genomics in Mexico by using high-quality technologies like the sequencing we do in the lab, with a focus not only on health or clinical applications but also heavily on conservation,” Hernández explained.