Did you know that your sweat can generate electricity, besides providing information about your health? This research is being carried out at the National Laboratory for Microfluidics and Nanofluidics at the Center for Research and Technological Development in Electrochemistry, (known in Spanish as CIDETEQ), which has been running since 2016 in the city of Querétaro, Mexico.

Luis Gerardo Arriaga Hurtado, leader of this national laboratory, explains that the goal of this research center is “the conversion of energy, storage, the use of hydrogen, liquid fuels (ethanol, glucose), CO2, and utilizing other non-conventional fluids such as sweat, blood, or urine, which have analytes that can be oxidized and may work as fuels”.

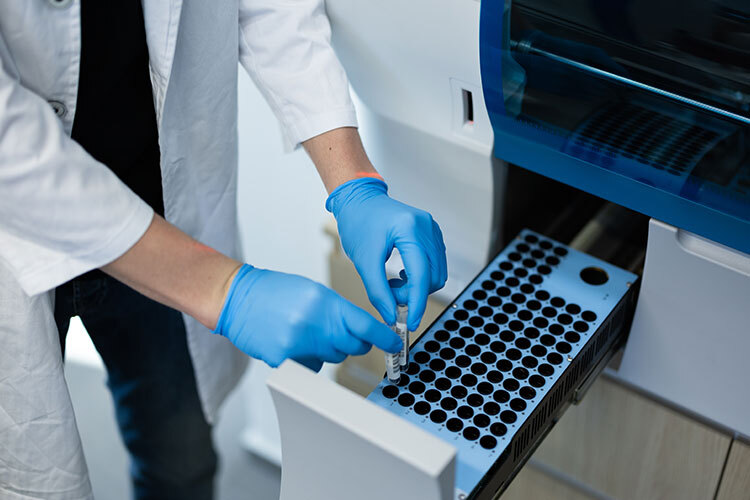

Sweat, blood, and urine? Yes, you read that right. The laboratory, which is funded by the National Council of Humanities, Science, and Technology (known in Spanish as CONAHCYT), has developed a patch a few centimeters wide that’s placed on the upper back of someone who’s doing exercise to generate electricity from sweat.

“When someone’s sweating, we put a patch on them that generates energy from that sweat; we can also obtain information on their glucose levels from that fluid,” explains Arriaga.

The National Laboratory for Microfluidics and Nanofluidics, which has been running since 2016, specializes in researching the behavior, manipulations, and control of fluids confined in structures on dimensions at the micro and nano scales. What’s more, it’s working on the development of devices such as the aforementioned patch and other types of biosensors.

What Other Projects Is This CIDETEQ Lab Working On?

Regarding other projects developed at this CIDETEQ lab, Arriaga said during a seminar hosted by Tec de Monterrey’s Institute of Advanced Materials for Sustainable Manufacturing: “We’ve developed electrodes to measure chlorine, which tell us about levels of dehydration, potassium, uric acid, and glucose.”

Another of their developments focuses on electrocatalysts known as microfluidic fuel cells, which enables them to create energy conversion and storage systems.

“These have two electrical conducting plates between which flows an oxidant with electrolyte and a fuel that enables us to produce energy, water, and reduce CO2,” adds the specialist.

Over the past eight years, they have created seven generations of cells with dimensions from hundreds of microns across to the most recent version, in which the liquid flows through cavities in the 70 to 90 nanometer range.

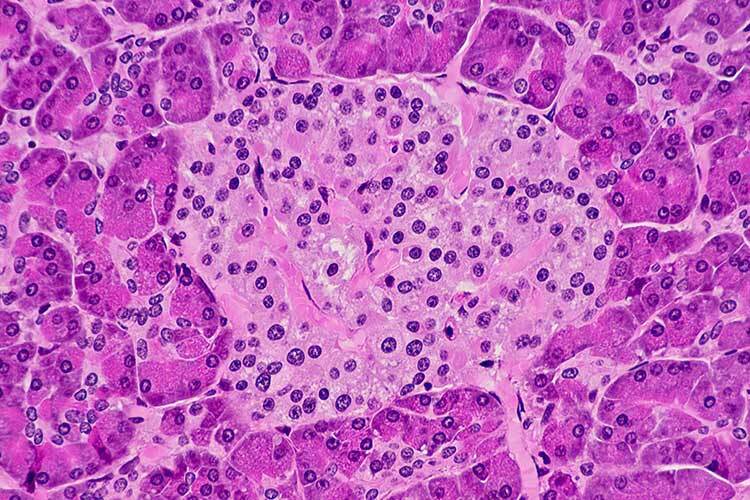

What’s more, the lab has collaborated on a project to develop miniature sensors capable of early detection of breast cancer cell formation. According to Arriaga, this emulates the functions of an organ on a chip that can eliminate or break down these cells.

In the future, the lab will be working on an autonomous system to generate energy in microfluidic systems: “The idea is for the pressure of this liquid to generate a piezoelectric effect,” remarks Arriaga.

Scientists from different disciplines are required to research and develop these devices, such as mathematical physicists, biotechnologists, programmers, nanotechnologists, and biomedical specialists.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Please write to our content editor to find out more at marianaleonm@tec.mx.