Fungi are among the most versatile organisms on Earth. Some serve as food for other species, those that make us hallucinate, and those that generate enzymes that could help us clean contaminated water, among many others.

“In biotechnology, the idea is to take the tools that nature already has and direct them toward very specific things, like combating water pollution,” says Nancy Ornelas, research professor at the School of Engineering and Sciences at Tec de Monterrey and member of the Water Center, in an interview with TecScience.

In Mexico, water pollution is one of the country’s biggest environmental problems. According to a study by the National Water Commission (CONAGUA), 59.1% of Mexico’s surface water is contaminated.

The problem grows due to the lack of capacity of treatment plants, which currently only clean 43% of municipal wastewater.

For Ornelas, part of the solution is to combine the use of biotechnology, nanotechnology, and nature-based solutions to complement the work done in these plants to ensure that water in Mexico is of better quality.

Fungi to Treat Polluted Water

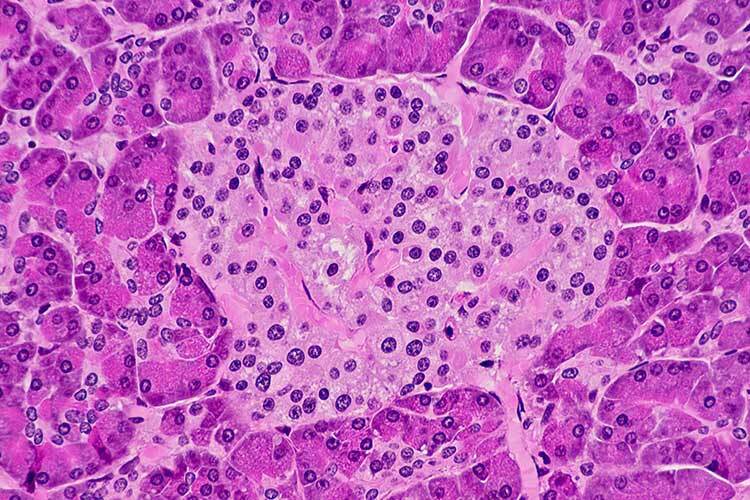

In 2015, she and her group went out to the forested areas of Monterrey in search of a fungus that is distributed in the world’s tropics, grows on dead trunks, and feeds on them. Due to its red and orange hues, it was named Pycnoporus sanguineus –sanguineus from the word sangre, which means blood–.

“The fungus releases substances that are very effective in the degradation of organic matter, such as wood, to break it down and be able to feed on it,” explains Ornelas.

These substances are enzymes—organic molecules that catalyze chemical reactions—particularly those secreted by Pycnoporus s. are called laccases and can degrade lignin. This compound makes up the bark of tree trunks.

Based on scientific literature, Ornelas and her team had the idea of testing the enzymes to see if they degraded other organic compounds in polluted water.

After finding the fungus and moving a sample to her lab, her team spent the next few years characterizing, isolating, and purifying the enzymes, using small bioreactors and feeding the fungus tomato juice.

Once they managed to isolate and purify them, they tested them in tap water, river, lake water, and wastewater effluent from treatment plants.

“These enzymes turned out to be very good at breaking down emerging contaminants, which are problematic nowadays,” she says.

Emerging contaminants are those whose presence in water is known, but until recently, we discovered that they present a risk to human and environmental health. Few Mexican plants have filters to treat them specifically.

A Local, Efficient (and Affordable) Way

In one of their studies, Ornelas and his team collected samples from agricultural and domestic water wells in the La Paz Valley, Nuevo León. They demonstrated that a cocktail of laccase enzymes removed 50% of the Diclofenac and more than 70% of other organic compounds in the water.

This was replicated with samples from various bodies of water with different degrees of contamination. “The best thing about these enzymes is that you just have to put them in the water; if it is very polluted, you just add a larger amount,” explains the researcher.

To strengthen their line of research, they have also used different nanotechnology methods to immobilize the enzyme in tiny devices that allow them to be reused for up to ten continuous cycles of contaminated water treatment.

According to the expert, although her research is basic science and has not been scaled to an industrial level, this is a local, efficient, affordable, and environmentally friendly way to modernize treatment plants and prevent their effluents from contaminating rivers, lakes, seas, and groundwater.

“The amount of enzymes we produce is enormous, equivalent to what it would cost me 58,000 or 11,000 USD if I bought them at Sigma Aldrich,” says Ornelas. Sigma Aldrich is an American chemical company with synthetic enzymes similar to those purified by her group.

Their operation costs are meager since preserving the fungus is relatively simple, feeding it is cheap, and purifying the enzymes is also cheap. “What we use the most is electricity because of the bioreactors, but if we also used solar panels, it would be an even more sustainable option.”

Currently, her group is studying the possibility of using these same enzymes to degrade microplastics, a growing pollution threat worldwide.

For her, the hope is that nature-based solutions will become increasingly used globally. “The whole issue of water treatment is moving towards biotechnological treatments due to their simplicity and sustainability,” concludes Ornelas.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx