The accumulation of thousands of tons of sargassum along the coasts of the Mexican Caribbean is an environmental challenge that poses serious threats to ocean ecosystems and marine species. It also impacts local economies, tourism, and even public health. In response, researchers at Tec de Monterrey are developing projects to turn this abundant macroalga into a valuable resource for various industries.

Georgia María González, a professor of Bioengineering at the School of Engineering and Sciences at Tec de Monterrey, and a researcher at the Institute of Advanced Materials and Sustainable Manufacturing, along with Leonardo Farfán, a research professor in the Department of Mechanics and Advanced Materials at the Puebla campus, have been working on a project to evaluate how oils extracted from sargassum can enhance the properties of synthetic lubricants and potentially replace them.

This project was funded through the Challenge-Based Research Funding Program 2022 and focuses on leveraging the abundance of sargassum to produce an oil that can serve as an additive in synthetic lubricants, which are commonly used in car engines and industrial machinery.

“Lubricants are essential because they reduce friction between metal components in any machine, ensuring energy efficiency in their operation. The core idea behind this project was to use macro- and microalgae to develop additives that help transition from 100% petroleum-based lubricants to incorporating bio-oils,” explains González.

Through this project, which also involved researchers from the Instituto Politécnico Nacional (IPN), it was demonstrated that adding just 10% sargassum oil into a synthetic lubricant (PAO6) could enhance viscosity levels while also reducing engine wear. This finding highlights the significant potential for greater efficiency and durability in engines and machinery.

Sargassum Oil as an Additive in Synthetic Lubricants

When González talks about a transition, she refers to the ultimate goal of reaching 100% bio-oil usage. However, she acknowledges that “as of today, car engines and factory machinery are not yet ready for that change. So what do we propose? Gradually incorporating these oils as additives.”

For this project, the researchers tested a formula composed of 10% algae oil and 90% conventional lubricant. They selected PAO6 because it is the standard lubricant used in laboratory tests and is commonly found in vehicle and factory machinery.

The tests conducted with this formulation showed that its viscosity decreased—at temperatures of 40°C and 100°C—by up to 15%. This reduction means less resistance in machine operation, leading to lower energy consumption. A useful comparison is water versus honey: honey has a higher viscosity, making it thicker, harder to flow, and requiring more effort to handle.

On the other hand, the viscosity index increased by 26%, helping the lubricant remain more stable across a wide range of temperatures. This indicator relates to how viscosity decreases with heat, allowing mechanical parts to move with less effort.

Additional tests measured the wear footprint and friction coefficient, revealing that the sargassum-based additive improved metal part protection in engines by up to 10% compared to pure PAO6.

In other words, the 90-10 lubricant formula could help prevent engine, gear, and mechanical part deterioration while potentially extending the lifespan of machinery and vehicles.

Collection and Processing of Sargassum

Since 2011, the Mexican Caribbean has been invaded each year by sargassum, a macroalga from the Sargassum genus. In 2023, media reports indicated that the Mexican Navy collected over 20,000 tons of it. Scientists are also evaluating its impact in different areas, such as damage to marine flora and fauna due to light obstruction and changes in water chemistry. Additionally, as it decomposes, sargassum releases substances like heavy metals and gases such as hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, and ammonia—compounds that can pose health risks with continuous exposure.

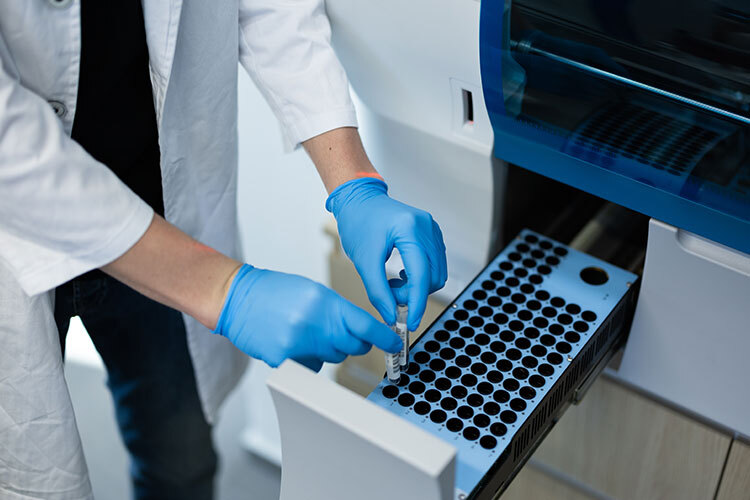

As part of the project, researchers partnered with members of the hospitality industry, who had been affected by the excessive presence of sargassum and had invested in teams of biologists to tackle the issue. It was agreed that hotels would collect the sargassum and send it to Monterrey via air courier within 12 hours to preserve its freshness.

Once received in the lab, the researchers washed the algae, dried it in ovens, ground it into a fine material, and used chemical solvents to extract the oil. González acknowledges that these solvents are not environmentally friendly. However, they were necessary for this stage of the research to obtain the oil and analyze its potential in synthetic lubricants. In future phases, the team aims to standardize the process and explore more sustainable extraction methods.

After extracting the sargassum oil, the team sent it to the Department of Mechanics and Advanced Materials at the Puebla campus, where it was blended in different proportions with conventional lubricant for tribological testing—evaluating friction, lubrication, and wear.

“This type of study is entirely new. The extraction of oils is still in its early stages and not yet fully standardized. There are very few scientific articles discussing the use of macro- and microalgae oils in biolubricant applications,” explains González.

Microalgae Oil Also Under Evaluation

González explains that alongside the study on sargassum oil, the team also developed a biolubricant formula using microalgae cultivated in the lab. This compound followed a similar approach, blending 10% algae oil with a commercial automotive lubricant.

After a selection process, the researchers chose the Scenedesmus species, a microalga—essentially a photosynthetic single-celled organism—that they successfully grew even in wastewater from pig farming. This species was selected due to its high oil content. The process was carried out at a pilot scale using six 100-liter reactors.

Since the cultivation medium was liquid, the team used a centrifugation process to separate the microalgae. Once they obtained the biomass, they used the same solvents previously applied to sargassum to extract the oil.

The resulting blend produced a more fluid oil with greater lubricity, but only at temperatures below 137°C to preserve its properties. “That’s an important factor,” González points out. “For example, car engines don’t typically reach that temperature, but heavy-duty machinery often exceeds it, requiring a different type of lubricant—one that’s more viscous and grease-like.”

Algae vs. Land-Based Plants

The development of plant-based lubricants is not a new concept, says González. It began gaining traction in the 1980s and 1990s. However, most of these bio-oils have been derived from land-based plants, which is costly and creates competition for agricultural land—forcing a choice between using it for food production or lubricant manufacturing.

In this regard, micro- and macroalgae offer a significant advantage over other bio-oil sources like palm or sunflower. They can be cultivated in wastewater or saline environments, eliminating the need for freshwater resources. In the case of sargassum, there’s no need to invest in its growth—only in its collection from the ocean.

González explains that the study evaluating the benefits of algae oils as additives has now been completed. However, she points out that the next phase should focus on assessing their toxicity in ecosystems and their degradation time in the environment, which should ideally be shorter than that of conventional lubricants.

“With these 10% algae-based additives, we are proposing a transition to more sustainable products. We’re betting more on sargassum because we’re not investing anything in cultivating it. The only costs would be collection, oil extraction, and formulation,” says González.

Were you interested in this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more about marianaleonm@tec.mx