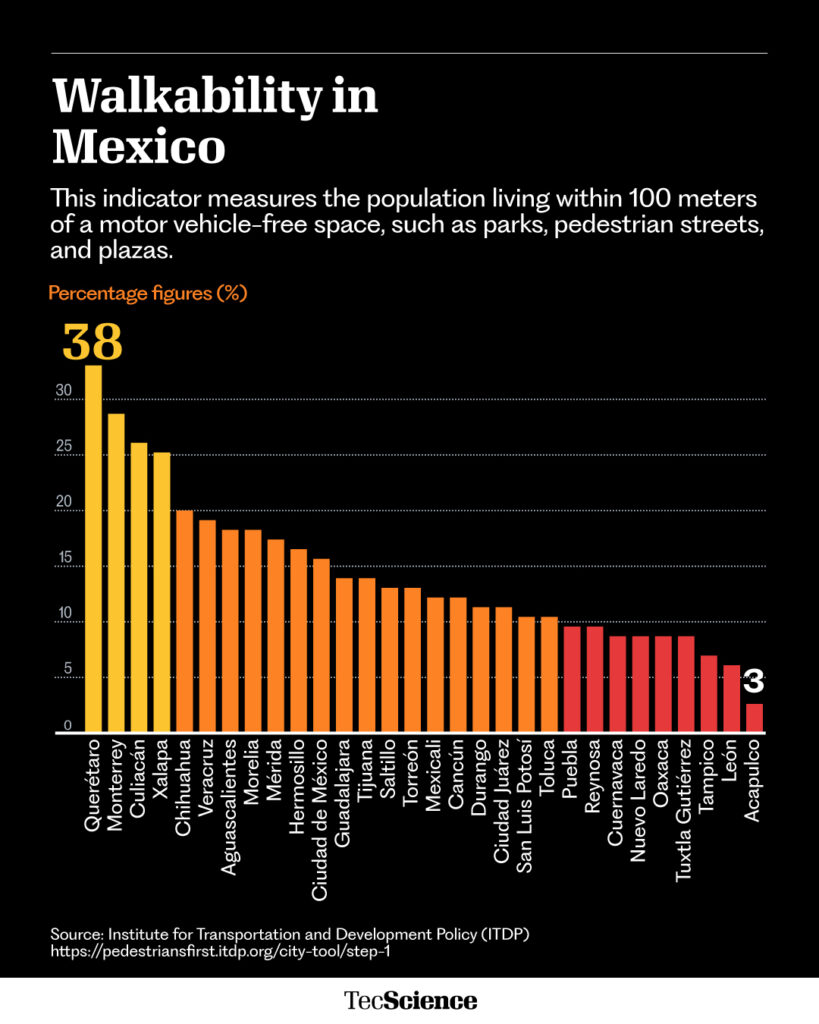

Walking is a key part of an active lifestyle that depends on favorable urban and social conditions—factors that must be shaped by thoughtful planning and public policy to ensure walkability that is dignified, safe, and equitable, says Eugen Resendiz, a researcher at the Center for the Future of Cities (CFC) at Tec de Monterrey.

It’s a fundamental form of physical activity that contributes to a healthy lifestyle and offers numerous preventive health benefits. Walking lowers the risk of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and Alzheimer’s, and it also supports better mental health.

However, in Latin America, where roughly 30% of all trips are made on foot, most of those walks are born out of necessity, not choice. “People walk because they have to, even if the environment is terrible. The idea is to improve that experience so walking can become enjoyable. It’s the most equitable, affordable, and sustainable way to get around.”

Through two separate projects, researchers at the CFC are aiming to understand what walking experiences are like in urban areas and what specific factors encourage more walking among Mexicans, not just out of necessity, but as a recreational activity in dignified settings with appropriate safety measures. Another key goal is to produce scientific evidence that can inform urban planning policies to foster better walkability.

Urban Regeneration for Walkability in Distrito Tlalpan

The first project, Walkability in Distrito Tlalpan (DiT), was funded by the Challenge-Based Research Funding Ruta Azul Program 2023. It aims to understand how urban models are transferred from one place to another—in other words, whether designs from other countries can be adapted and replicated in Mexico, and whether, due to various factors, they will ultimately succeed or fail.

The project is led by researchers Roberto Ponce from the School of Government and Public Transformation and the CFC, and Ryan Anders Whitney from the School of Architecture, Art, and Design (EAAD). It focuses primarily on the area of Distrito Tlalpan, which is also home to Tec de Monterrey’s Mexico City campus.

Their research has two components. The first is qualitative, involving interviews, focus groups with residents, business owners, and students, and meetings with the DiT team to explore knowledge of initiatives impacting walkability. Through this process, the researchers identified 18 key stakeholders across the public, private, social, and academic sectors who play a role in urban regeneration projects. Among their findings: a noticeable disconnect among the various actors, and a pressing need for mechanisms that encourage greater community participation in decision-making.

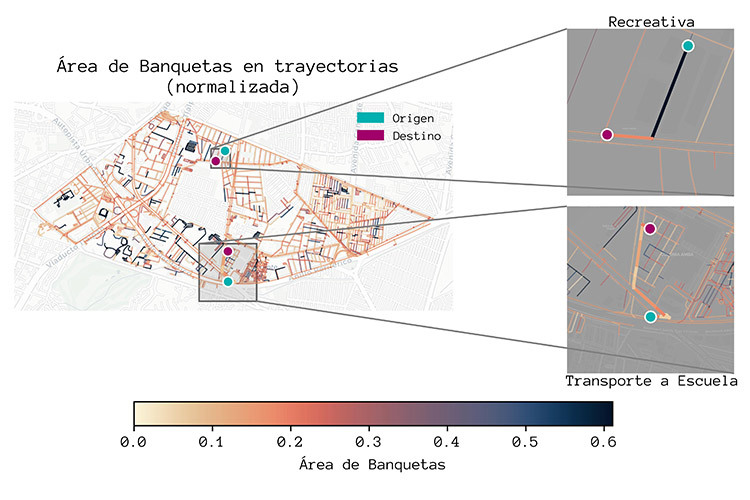

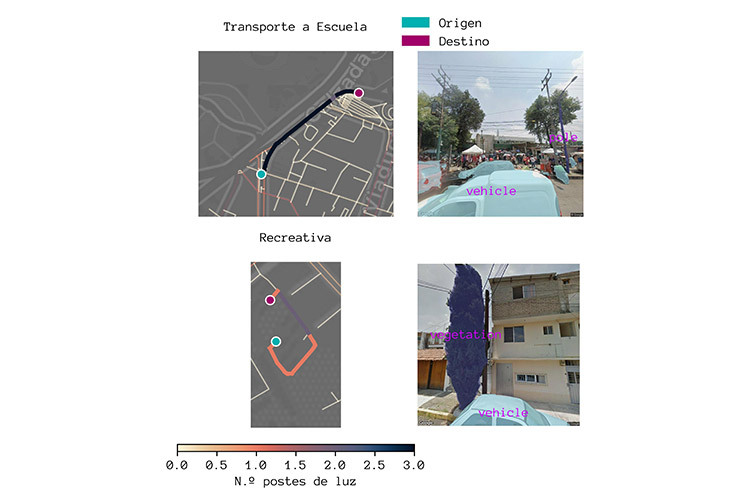

The second component, on the other hand, took a quantitative approach, using technology to identify features that impact walkability and pedestrian experience. By analyzing urban spaces with Google Street View and computer vision tools using image segmentation, the team was able to detect elements like trees and sidewalks in the built environment along walking routes. “We worked with Rounaq Basu, a professor at MIT, who developed an algorithm called Madina that helps simulate what would happen if you intervened in certain streets,” says Resendiz.

The study focused on three types of walking trips: recreational walks, walks from residential areas, and walks from transit stations to schools and businesses. For instance, in the latter category, researchers found that sidewalk areas are 10% smaller than those in recreational zones, there is 18.5% less vegetation, 53% more buildings, and a higher number of vehicles.

With the data gathered, the team aims to develop a decision-support system that can evaluate the impact of urban regeneration projects on walkability, one that could be replicated in other cities and Tec de Monterrey campuses. “Walking should be a central element of urban design. In Mexico, one of the challenges is making walking something ‘cool,’ the way it happened with cycling. It needs to become a choice, not just a necessity.”

Walking to the Metro in Monterrey and Mumbai

The second project is an international collaboration carried out through studies in Monterrey, Mexico, and Mumbai, India—both considered cities of the Global South, meaning they are located in developing countries with significant political, social, and economic inequalities. The research focused on the various factors that influence the walking experience for metro users in these urban settings.

The initiative, Walking across borders: exploring challenges to walkability in the Global South, brings together researchers including Joseph Ferreira from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Ahana Sarkar from the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IIT Bombay), as well as Ponce, Resendiz, and Nélida Escobedo from the CFC and the EAAD at Tec de Monterrey.

Funded by the Volvo Research and Educational Foundation, the project’s goal is to identify the needs and obstacles affecting the pedestrian experience through a comparative analysis of walkability in areas near metro systems in both cities. In Monterrey, for example, perception surveys were conducted with around 600 people to assess differences between their neighborhoods and the environment around metro stations.

The survey results reveal that walking experiences are shaped by a range of urban conditions, including pedestrian crossings, greenery and shade, street cleanliness, the presence of benches or street vendors, lighting, infrastructure, and available amenities. Social factors also play a critical role, such as street harassment, crime, and traffic safety. For instance, even if an area is well-equipped, if people don’t feel safe, their walking experience will be perceived as negative.

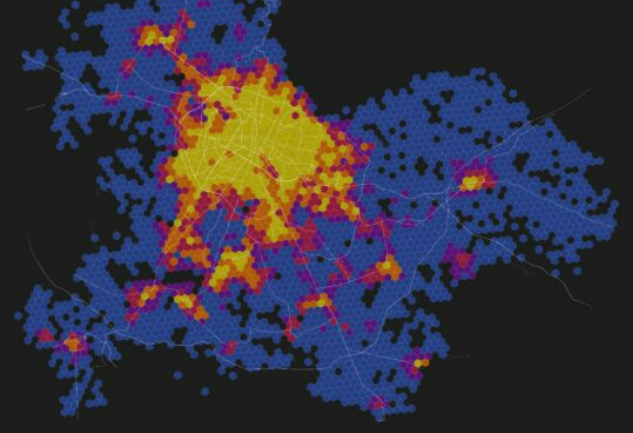

The study also includes a component that explores street-level elements using computer vision, algorithms, and Google Street View. “We’re conducting an analysis called Structural Equation Modeling to examine how each of these key factors plays a role in the walking experience,” explains Resendiz.

Improving these walking routes could not only increase the number of trips made on foot but also boost the use of public transportation, leading to more efficient car usage and helping to meet climate goals.

Resendiz adds that the study incorporates a gender-sensitive approach, allowing for comparisons between men’s and women’s perspectives. The research team is working on an additional scientific publication focused specifically on women’s perceptions of their walking experiences in these areas.

One of the team’s goals is to develop an interactive, visual platform that can serve as a tool for designing urban spaces and policies to enhance the way pedestrians interact with their surroundings.

Keys to More Walkable Cities

Ryan Anders Whitney, a research professor at the EAAD, Mexico City campus, emphasizes that transforming cities into more walkable places requires a strategic vision focused on long-term projects—initiatives that extend beyond election cycles and changes in administration. “This can’t be achieved one project at a time; what’s needed are enduring connections between political actors.”

He points out that fragmented governance is a complex challenge that’s difficult for all stakeholders involved in walkability issues to navigate. To address this, he proposes a transparent system that facilitates the coordination of urban projects with a forward-looking perspective.

Whitney also highlights equity as a key factor in improving walkability across cities. Urban areas vary widely in their suitability for walking; for instance, some neighborhoods, though heavily trafficked by pedestrians out of necessity, may be extremely unsafe. “We need to work toward a more equitable approach in how we promote walkability in different parts of the city—creating cohesive, supportive environments for safe and healthy walking.”

Interested in this story? Want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more: marianaleonm@tec.mx