Researchers at Tec de Monterrey have developed the Heliodome, a solar simulator that reproduces sunlight conditions from anywhere in the world inside a laboratory.

The device is capable of precisely simulating solar radiation, temperature, and the sun’s position in the sky.

This allows scientists to test the efficiency and durability of solar technologies such as photovoltaic panels, green roofs, and materials like waterproof coatings and thermal insulators.

How the Heliodome Works

José Rodrigo Salmón Folgueras, a research professor at Tec de Monterrey’s School of Engineering and Science (EIC) and one of the project leaders, explains that the team achieved these simulations by adjusting variables such as irradiation, light direction, tilt angle, and temperature.

“You can move the light source as if it were the sun, change the angle based on the time of day or season, and adjust the intensity. And even if it’s raining outside, the conditions inside the lab stay exactly the same,” he notes.

The Challenge of Testing Solar Technologies Outdoors

Before the Heliodome, testing relied entirely on the weather, which caused delays and added uncertainty to the results. Experiments were typically conducted outdoors and had to be scheduled based on forecasts predicting ideal weather conditions.

For instance, if researchers wanted to analyze how a technology performed in winter, they had to wait for that season to arrive. Even on clear, windless days with consistent solar radiation, a sudden change in the weather could ruin hours’ worth of collected data.

This need for constant, controlled conditions to ensure reliable testing—both for their own innovations and for consulting projects with companies—led the team to seek out a solution, explains José Luis López Salinas, a researcher at the EIC and advisor on the project.

“We needed a controllable light source that could mimic the sun, and nothing like that was readily accessible to us,” López Salinas says.

Developing an Accessible Alternative

The team conducted a global study to identify patents and commercial alternatives. However, they found that existing devices were either too expensive or too large—designed for industrial-scale use—or had limitations when it came to replicating key elements like temperature or the spectrum of solar radiation throughout different times of the year. In short, they lacked the versatility their experiments required.

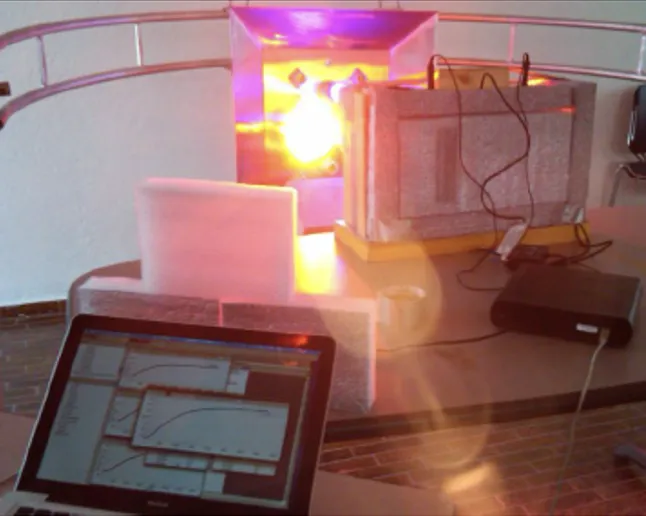

Over the course of more than a year, the researchers developed their own solution: a low-cost device equipped with a variety of light bulbs, including incandescent, halogen, fluorescent, infrared, and ultraviolet.

The result was a matrix of around 30 lamp combinations that can realistically simulate solar radiation based on the time of day or season in any given city.

Validation with Real-World Data and Computer Simulation

To ensure the simulator reflected real-world conditions, the team validated the system using both international databases and field measurements. To do this, they relied on international platforms such as the Photovoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS).

They also used sensors to collect field data—temperature, humidity, solar irradiation, and spectrum—and adjusted the system’s parameters to match real-world scenarios, such as a sunny summer afternoon in Mexico City.

“We conducted a statistical experiment to fine-tune and calibrate the Heliodome, using experimental data, international databases, and computer simulations,” explains Salmón Folgueras, who adds that this is a project that has been evolving since 2011.

Structure and Types of Simulated Radiation

Today, the device consists of a metal arch-shaped structure that allows spherical movement, with a movable lamp or light source that can be manually adjusted to mimic the sun’s movement at various angles. Its configurations also make it possible to control variables such as solar irradiation, its direction, and the temperature an exposed object receives.

The various combinations of bulbs also enabled the replication of three types of radiation associated with sunlight:

- Visible light: reproduces the sun’s actual visual conditions.

- Infrared radiation: linked to the thermal behaviour of materials and responsible for increasing the temperature of exposed objects.

- Ultraviolet (UV) radiation: enables the simulation of material degradation or photochemical reactions.

Beyond serving as an experimental tool, the device is seen by the researchers as a technological system that can be replicated and scaled. Following the development of the first prototype, they published a scientific article detailing its design and functionality and also took steps to protect their innovation.

“The Heliodome is already patented, specifically for the way it mimics the sun’s movement, controls irradiation, and allows for the modulation of temperature and radiation—those are all part of the system,” emphasizes Salmón Folgueras.

Applications in Solar Technologies and Other Systems

Rubén Eduardo Sánchez García, a researcher at the EIC and a member of the development team, explains that beyond validating the device’s functionality by comparing it with field data, the Heliodome has been used to evaluate photovoltaic panels, solar thermal collectors, and materials such as waterproof coatings, thermal insulators, and green roofs. It’s also been applied to other technologies the team is developing, including a prototype for a portable solar stove.

“With the stove, we spent about a week running tests in series, every single day. We had the same conditions each time—the same angle, the same temperature, the same irradiation—and then we compared the results. You just can’t do that outdoors; it’s impossible outside,” says Sánchez García.

The device has also been used to test photobioreactor systems for monitoring the growth of plants and microalgae for biomass and biofuel production, as well as in bioclimatic architecture, energy audits, and greenhouse applications.

Industry Interest and Corporate Collaboration

Salmón Folgueras adds that the wide range of applications offered by the device has attracted interest from several players in the industry. This has led the team to collaborate with companies such as Cemex, Johnson Controls, Rotoplas, Acmel Labo, and Schneider Electric, among others, to validate various solar products and technologies. “We’ve even been asked if it can be licensed or sold,” he notes.

The development team also includes researchers Orlando Castilleja Escobedo, a specialist in computational fluid dynamics, and Bárbara Arévalo Torres, who focuses on the system’s experimental and instrumentation components.

The current version of the Heliodome is still a prototype and must be operated manually. That limitation has led the team to set new goals aimed at scaling the technology toward automation—so that by simply entering a city and time into a computer, the system would configure itself to simulate those conditions without any human intervention.

“We also want to add sensors that provide real-time feedback and confirm whether the programmed conditions are actually being met. Eventually, we could even integrate artificial intelligence to optimize the entire process,” says Sánchez García.

Looking ahead, the researchers hope the Heliodome will become an accessible and accurate alternative for testing all kinds of solar technologies, both in research labs and industrial settings.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx