Imagine a Super Bowl without a bowl of guacamole and totopos at the center of the table. While that seems impossible today, this essential side dish in the football ritual wasn’t the norm in the United States before 1994. The reason: a quarantine banned Mexican avocados from entering the country.

Everything changed when two EXATEC led studies that scientifically dismantled that blockade and transformed the avocado industry forever.

The quarantine that stopped Mexican avocados

The problem began in 1914, when the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) imposed a quarantine after detecting the avocado seed weevil in Mexican fruit, a pest that affected some avocado varieties.

From then on, Mexico repeatedly requested that the USDA reassess the risk. However, for decades, all petitions were rejected.

NAFTA reopens the debate

In 1992, as Mexico, the United States, and Canada were closing negotiations on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Mexican government seized the opportunity to reopen the issue. But this time with a specific request: to evaluate the risk of Michoacán Hass avocados, a variety with thick, rough skin, very different from the thin-skinned criollo variety, which is vulnerable to pests.

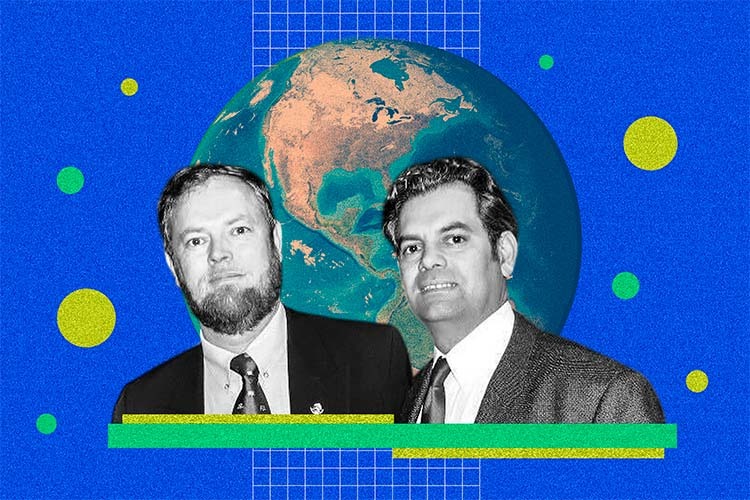

Walther Enkerlin, agricultural engineer, explains that in publications reporting the interception of avocados with pests such as fruit flies, «they were Caribbean or Central American varieties, but not the Hass variety. That’s where there was no scientific evidence [for the quarantine]».

The first study: evidence of Hass resistance

When APHIS agreed to reopen the evaluation, Enkerlin was working at the MoscaMed program, which made him the natural candidate to lead the study on whether Hass avocados could be considered pest carriers.

His team exposed fruit and trees to three species of fruit flies—Anastrepha ludens, A. serpentina, and A. striata—under forced conditions, confining them in cages both in the field and laboratory. After several days of observation, the pattern was clear: harvested fruit became more susceptible as they ripen. Starting at 20% dry matter, A. ludens could successfully oviposit; the other species showed lower efficacy.

In contrast, forced infestations on avocados still attached to the tree did not allow larval development. The team summarized the findings as follows:

- Fruit on the tree: zero infestations.

- Harvested fruit with >20% dry matter: infestation possible, especially by A. ludens.

- Harvested fruit before 22% dry matter: virtually no risk.

With this evidence, Enkerlin defended the study at a public hearing in Washington before scientists and allies of the California Avocado Commission (CAC). But the protocol had already been validated by three USDA researchers—Bob Mangan, Allan Green, and Ed Miller—. «When the APHIS director asked them if they had any comment about the work, all three stayed silent. They agreed with the results», Enkerlin recalls.

In February 1997, thanks to this data, guacamole made with Mexican avocados entered American homes for the first time —legally— for the Super Bowl.

The second study: International validation

The fight continued. The initial opening was limited: 13 states and only four months a year. Additionally, the California Avocado Commission (CAC) kept questioning the evidence.

“The first article [by Enkerlin] was published in Folia Mexicana Entomológica, a very honorable journal”, recalls Martín Aluja, also an agricultural engineer from Tec and then a researcher at the National Institute of Ecology (INECOL). “But technicians from the United States argued that it lacked international prestige”.

To strengthen the scientific foundation, the National Service for Agrifood Health, Safety and Quality (SENASICA) commissioned Aluja to conduct a second study that would replicate and expand on the previous work. His design was more rigorous:

- They evaluated more trees and more fruit.

- Forced infestations were conducted during both dry and wet seasons.

- A CAC inspector was present at all times.

“They told me: ‘You’re crazy, Martín. They’re the ones who don’t want Mexican avocados.’ And I replied: ‘That’s precisely why I want them to certify that this research is 100% honest and transparent’”.

Even with that rigor, they faced difficulties. “A producer applied an agrochemical prohibited by the protocol”, Aluja remembers. The incident forced them to report the error and repeat the study a month later, when fruits are most vulnerable. To make conditions worse, one of the sampled trees had roots weakened by a fungus. “And worms appeared in those fruits”.

The finding, which seemed disastrous, turned out to be decisive. “Fortunately, those larvae reached the pupal stage, but no adults emerged from those pupae. Imagine how fantastic: under extreme conditions and with a weakened plant, the fly reached the larval stage but couldn’t become an adult. That was much more powerful scientific evidence”.

The study, published in the Journal of Economic Entomology, finally obtained the international recognition that was needed.

The complete opening of the market

With both studies endorsed by APHIS and the CAC, the USDA definitively opened the U.S. market to Mexican Hass avocados in 2007.

Within a few years, Mexico became its main supplier. Today, exports exceed 3.5 billion dollars annually, according to the Association of Avocado Producers, Packers and Exporters of Mexico.

New risks: deforestation, climate, and lack of genetic diversity

This accelerated growth has also created new problems: deforestation, climate vulnerability, and pressure from organized crime.

From the beginning, Aluja warned of something critical: “Take care of the water and look alive, because the Hass avocado you have in Michoacán is basically a clone of one tree. In other words, you have no genetic diversity in your crops”.

Without that diversity, he explains, trees cannot adapt to new environmental conditions. If temperatures rise and pests expand their geographic range, crops could face massive losses.

”It’s a time bomb”, the researcher states. Furthermore, he feels sorry that the industry hasn’t invested in research, despite the enormous benefits obtained. “You solve a monumental problem for them, they have an epic gain, because it’s unimaginable and, from both the United States and Mexican sides, they lacked the vision to generate a huge fund for research of this nature on other crops”, he explains.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx