In Paso del Norte, a town in the Mexican state Chihuahua, a highway separates the community from the center of the capital. For its inhabitants, the only way to cross over to go to work, the doctor or to buy groceries is to cross a pedestrian bridge in poor conditions and with steep stairs.

“This access is very problematic, especially for older people or people with disabilities,” says Emanuele Giorgi, research professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design (EAAD) at Tec de Monterrey in an interview with TecScience.

To contribute to reducing the vulnerabilities faced by the people of this village− and three other communities in Chihuahua− a group of architects and urban designers from the EAAD brought them solutions based on technology, awareness and multidisciplinarity.

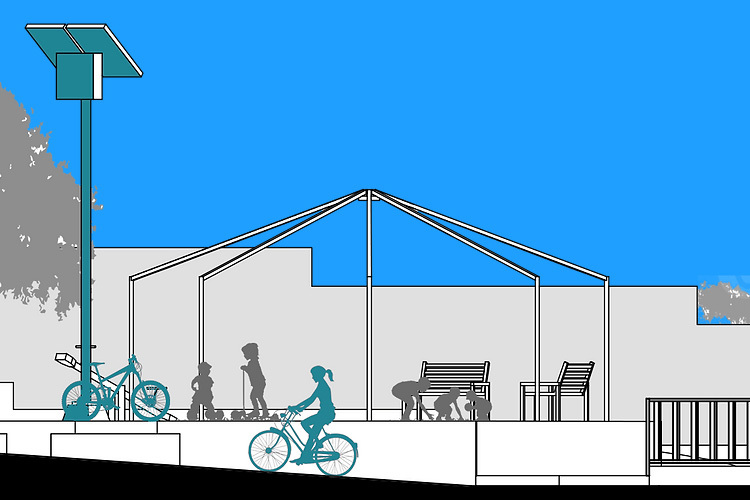

One of these projects, called Mobility HUB, brought electric bicycles and a solar panel to recharge them sustainably, with the intention of contributing to the mobility of its residents.

In addition, they gave them a training course to teach them how to transform a regular bicycle into an electric one with a motor.

“They gave me this bike a month ago, [and now] I use it to go to work,” says a woman who lives in Paso del Norte. “Here in the Paso del Norte we struggled with transportation, but thanks to it I can come and go easily.”

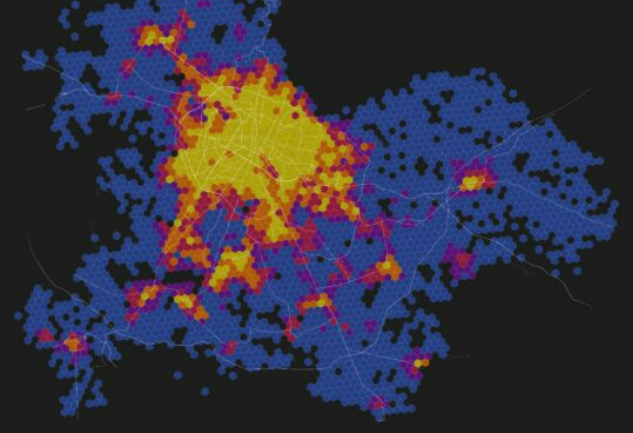

The reason why the inhabitants from rural populations in Chihuahua struggle with transportation is due to its territorial extension. With 247,455 square kilometers it is the largest state in the country.

However, 79% of its inhabitants are concentrated in urban areas, located in the municipalities of Chihuahua, Ciudad Juárez, Cuauhtémoc, Delicias and Parral.

The 21% of the population that lives in rural areas (disseminated in 63 municipalities) has to travel enormous distances to carry out their daily activities, facing extreme weather conditions, an imposing terrain and, in most cases, a great lack of infrastructure.

This is where architecture -which we generally associate with the construction of large buildings and luxurious finishes- comes in as a vehicle to empower vulnerable communities that face a lack of mobility and access to services, in addition to problems with insecurity and the absence of urban planning, among others.

Architecture to Reduce Vulnerabilities

Four years ago, the group of experts from EAAD , led by Giorgi, began reflecting on how design and architecture can help reduce vulnerabilities, resulting in the creation of the project Design for Vulnerables.

Little by little, they have managed to collaborate with the Paso del Norte, Nueva Delicias, La Regina and Basaseachi communities of Chihuahua to introduce technology-based solutions.

In their experience, they have found that it is essential that these types of projects be multidisciplinary. Also, it is important that the proposals contain raising awareness in the communities about how they perceive these vulnerabilities, how they affect them and the steps they can take to improve their situation.

The most important –and challenging– part has been finding a way for the projects to really provide a solution: “Many times, when the government, businessmen or philanthropists bring new resources or solutions, they do so through assistentialism, they give them something and they leave,” explains Giorgi.

This strategy often fails, since the communities do not learn how to use these technologies, they do not appropriate the new tools, they do not actively participate in the urban planning to introduce them and a collaborative relationship is not established with those who introduce them.

To avoid falling into this pattern, the EAAD group assisted to the communities and undertook a years-long process where they conducted interviews, excursions, walks, participatory mapping and collective reflections to detect social, environmental and economic risks.

Afterwards, they developed a vulnerability index to be able to propose strategies that contribute to solving the specific problems that affect each community.

Mobility HUB and Tech HUB

In Paso del Norte, the Mobility HUB project was well received by the community. One of the locals is even contemplating starting a business around them.

“I use the bike almost daily, it has helped me a lot to get where I want to go faster and to make the road less heavy,” says another of the beneficiaries. “I think it’s an option to form a business to transform old bicycles [into ones with motors] for the improvement of the neighborhood.”

In Tech HUB, they brought projectors, tablets, 3D viewers and speakers to schools and the community square to have interactive classes.

One of them was about first aid and sexual education, taught by the School of Medicine and Health Sciences.

“The idea is that these technologies can help didactic work and learning for the benefit of the community,” says Giorgi.

Agri HUB

In Nuevas Delicias, one of the greatest vulnerabilities the community faces is water scarcity. This is partly due to the fact that too much is consumed in agriculture and walnut tree cultivation.

“This tree consumes 1,000 liters of water per day, for each plant,” says Giorgi.

By working with the community’s primary, secondary and tele-high school, the Club del Abuelo (Grandfather’s Club) and the Agricultural and Livestock Union, they reflected on new ways of doing agriculture.

Together, they installed composts and smart greenhouses that measure temperature and humidity -accompanied by solar panels as energy sources- making them autonomous and sustainable.

The researchers also placed water harvesting systems in each greenhouse. “We gave training courses on how to use these composts and greenhouses and the idea is that in the coming years they develop community orchards,” says the expert.

Farmers were given drones and were taught how to use them, so they can monitor their crops and water leaks, without having to make long journeys.

Recently, the president of the Agricultural and Livestock Union had fallen from the horse on which he was doing the tour to review everything was working correctly and stayed there for a full day, since there was no cellphone signal.

“The drone will save them time, money and protect them from these risks,” he says.

Water HUB

In La Regina, one of the biggest problems is the contamination of water with arsenic and fluoride, which has triggered health problems, such as a higher incidence of cancer.

Until now, the solution imposed by the government had been the use of reverse osmosis plants: “100 liters of polluted water are taken, filtered through special membranes and returned clean,” says Giorgi.

However, these only clean up to 30 liters of the original 100, concentrating contaminants more in the remaining 70. This water is most often dumped back into the aqueduct, perpetuating pollution.

Currently, the United Nations prohibits their use, but in La Regina they are still used.

As part of the solution, the researchers partnered with a local company that works with activated carbon-based filters – which are not expensive and only require maintenance of around twenty dollars per year– capable of removing arsenic and fluoride.

“We installed them in four schools in the municipality with a faucet to the outside, so that anyone can go and fill their water containers,” says Giorgi.

Environment HUB and Tourism HUB

Finally, in the Sierra de Baseaseachi, mining has destroyed the territory and contaminated the land with heavy metals.

To help, the EAAD group started an environmental awareness and sustainable production project with the use of 3D viewers.

They also installed biodigesters to replace the wood stoves they use to heat school classrooms. “These take advantage of the organic waste from the dining hall to produce biogas,” says Giorgi.

In addition, they purchased air quality meters and gave them to the children of the local telesecundaria along with a notebook so that they can annotate the values they observe and participate in the environmental monitoring of their locality.

“The community has been very involved in these activities and they have been empowered by this information,” he says.

The Tourism HUB seeks to attract tourists who go to see the Piedra Bolada waterfall, one of the most beautiful and extensive ones in Latin America.

The idea is to collaborate with local hotel owners to create activities that attract people to not only visit the waterfall and go back, but also spend the night and watch the stars.

“We gave them a telescope, a cell phone adapter and a camera to start attracting responsible tourists,” says Giorgi. This could be an additional source of income that reduces the need for mining.

It is Essential to Create Close Connections With the Community

Together, the projects seek to reduce the vulnerabilities of these communities and, in addition, create knowledge through research that can be applied in the future in other places.

“We want to understand how architectural design, urban planning and service design have to evolve to facilitate the introduction of technological resources in vulnerable communities,” says the researcher.

In the groups’ experience, the most complex thing is getting the communities to want to participate, since they often distrust the intentions of those who arrive.

To achieve this, they established contact with people who already had some connection with the communities and little by little they built a close relationship with them, affirming their commitment to helping them at all times.

“Creating these ties was a long and demanding process, but now there is a very deep relationship of support and collaboration,” says Giorgi.

Did you find this story? Do you want to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more marianaleonm@tec.mx.