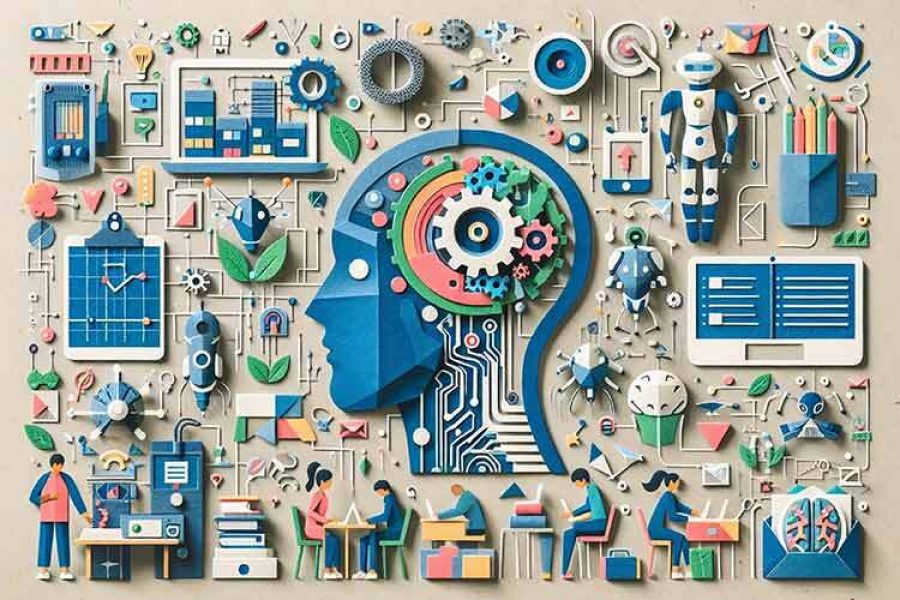

“Research is more than just publishing papers or producing articles—it’s about generating knowledge that reaches society,” said Jorge Valdez, Director of Strategic Relations at TecSalud and scientific editor at TecScience. “And at the same time, it should serve as a driving force to produce more research and to train researchers who will repeat this role.”

Valdez emphasized the importance of launching research projects during undergraduate studies, rather than waiting until graduate school for students to become familiar with the process.

This topic was the focus of a panel discussion featuring Jorge Valdez—who is also a physician and Tec graduate specialized in ophthalmology—and Nohemí Lugo, a professor in the Communication undergraduate program and the Digital Humanities master’s program, as well as a researcher in Education at the School of Humanities and Education at Tec. They were joined by two science students with hands-on research experience and backgrounds in science communication.

Challenge-Based Learning in Research

Regarding challenge-based learning models applied to research, Valdez explained that this approach brings education closer to real-world applications by presenting problems that require knowledge to solve or improve conditions—and learning through that process.

For her part, Lugo noted that research in the humanities and social sciences is oriented toward social, cultural, or political phenomena and aims to understand the lived realities of different social groups.

“It’s a form of research deeply tied to generating social change, creating public policy, educational innovation—sometimes even peacebuilding processes, gender equity, or improving quality of life for people with disabilities,” Lugo explained.

Approaching Research with Passion and Curiosity

While Lugo agreed that research challenges can be intellectually stimulating, she also warned that they can pose emotional hurdles and expose biases about scientific work.

“For instance, at first students tend to think of it as something boring… usually in earlier academic stages, we haven’t taught research through passion and curiosity,” Lugo observed. “I’ve spent years trying to figure out how to bring research closer to students in a more motivational way, regardless of the challenge—because sometimes those challenges feel like they’re imposed.”

One strategy that’s worked well for her is connecting projects to real-world problems that matter to students, whether stemming from their own communities or personal feelings of concern, indignation, or curiosity about the world around them.

“What I’ve discovered, after teaching qualitative methods to four different majors and then teaching communication research methods, is that performing research and becoming a scientist helps break the idea that it’s boring, that ‘I can’t do it,’ and instead links it to social change,” the professor explained.

Making an Impact from the Lab

Emilio Venegas, a sixth-semester Biosciences student, began conducting research back in high school with a thesis on biological systems in rats. Thanks to that early experience, he joined a research project at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences at just 21, studying cell cultures to better understand breast cancer.

“If I can get deeper into this biological field where impact is being made—even from a lab, without working with patient samples—we can still uncover the mechanisms behind diseases and treatments, as well as how they affect different molecules or tumor characteristics. I honestly found that fascinating and learned so much along the way,” he said.

Meanwhile, Luisa Liceaga, an eighth-semester Food Engineering student, recently completed a research stay at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, focusing on environmentally friendly techniques to analyze the stability of edible oils.

“I had the chance to run some experiments on my own, and that gave me the confidence to propose a hypothesis and an experimental plan—and then actually carry it out,” Liceaga said. “In my case, it really helped confirm that what I thought I liked is truly what I want to do. They even offered me the opportunity to pursue graduate studies in the same lab.”

The Importance of Science Communication

Alongside their early lab experiences, both Emilio and Luisa emphasized how vital it is to write, communicate, and share research findings—even if it doesn’t always come naturally to them or to many scientists.

“In the end, science communication is what fuels the entire scientific community. It’s what might inspire someone else to continue your research, to take a method or a piece of what you did, improve on it, and apply it to their own field,” Emilio explained.

For Luisa, who’s contributed sections to research papers in various projects, it felt like a valuable opportunity to clearly convey what had been discovered.

“That moment when you put the puzzle pieces together and try to express them in a way that others in your field can understand—I find that really rewarding,” Luisa added. “Sharing with others who are also making efforts in the same research area feels incredibly fulfilling.”

Professor Lugo mentioned that, in her experience, students can already produce high-quality research papers as early as their third semester—even within five-week challenge periods.

“I’ve learned that the top priority has to be on sharing and communicating,” said Lugo, who also highlighted the role of professors in encouraging outreach.

Valdez, meanwhile, stressed the value of writing in different formats, pointing out that writing helps researchers organize their ideas, give them coherence, and develop a rhythm.

“Hemingway wrote and wrote out of habit, he used to say, because it had to be done—not waiting for the muse to show up. He said it was something to do every day. And it’s the same for scientists: we have to sit down and write the paper,” Valdez remarked.

For him, writing a paper is also crucial as a collective process—especially when involving people from different disciplines and levels of experience.

“Nowadays, most of us operate more like small communities of hands-on learning. That lone scientist you see in movies—I’ve never seen that in real life, though it’s often romanticized… And today, students earn their place through their involvement, enthusiasm, and contributions,” Valdez reflected.

In the end, both academics agreed on the importance of “writing for the general public”—that is, promoting science communication using appropriate methods so that people without a scientific background can understand and engage with the content.

Did you find this story interesting? Would you like to publish it? Contact our content editor to learn more at marianaleonm@tec.mx