What if one day you ran out of tamales? Or tortillas for breakfast? While it might sound far-fetched, corn —the essential ingredient in these and countless other traditional foods— faces a silent enemy: pests. Among them is the maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais), a tiny insect capable of causing severe damage to stored grain.

But what if that enemy could be turned into an ally? Researchers from the Food Security group at the School of Engineering and Sciences (EIC) at Tec de Monterrey are exploring exactly that possibility: using the maize weevil as a source of protein that could reshape how we feed both people and pets, while helping protect the environment.

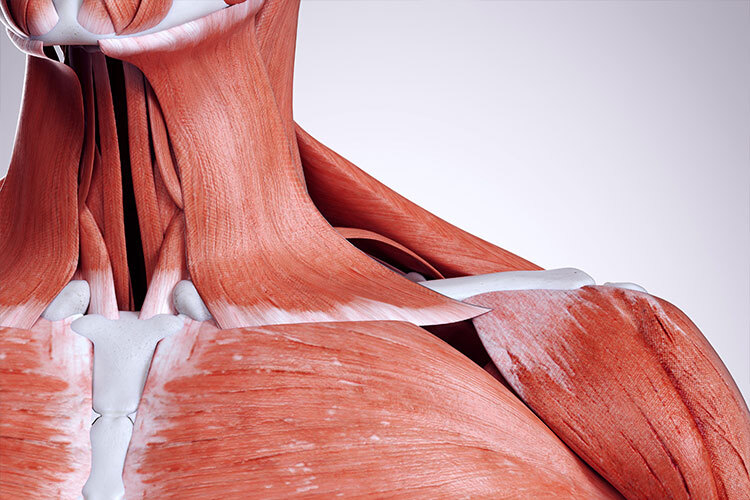

This tiny insect, about the size of a sesame seed, is estimated to cause weight losses of up to 76% and damage 100% of stored corn kernels.

“This project reminds us that we can find opportunities and solutions in unexpected places. In this case, we’re turning a pest into a nutrient that benefits the environment and the health of people and animals,” says Soledad Mora Vásquez, a Food Security researcher at the EIC, who leads the study alongside Silverio García Lara, also part of the team.

In their tests, the researchers found that the maize weevil is high in protein and can be cultivated easily thanks to its strong reproductive capacity. They processed it into a fine flour to make it more culturally and sensorially acceptable, offering a potential way to enrich foods such as tortillas, nutrition bars, baked goods, and even pet kibble.

Weevil: from Pest to Superfood

At the Postharvest Biotechnology Laboratory on the Monterrey campus, researchers raised maize weevils under controlled conditions, feeding them exclusively with corn. After a couple of months, they collected the insects, disinfected them, dried them, and ground them into flour. The result, they report, was a dark-colored flour with no unpleasant odor and a neutral taste.

Tests revealed that this flour contains nearly 50% protein. A large portion of that is made up of amino acids that the human body can easily digest. Its profile is similar to that of other edible insects, such as crickets or mealworms, and can be paired with legumes to further enhance its nutritional value.

Microbiological analyses also confirmed it is safe: no bacteria such as Salmonella, staphylococci, or E. coli were detected.

What’s striking is how efficiently the weevil pulls off this transformation. Feeding on corn—particularly the endosperm, the part rich in starch and protein—converts carbohydrates into protein with remarkable efficiency.

“It’s a super-efficient metabolic machine,” says researcher García Lara. “Where others see a pest, we see an affordable, high-quality source of protein.”

It’s also one of the most difficult pests to control in tropical regions due to its high reproductive capacity. In just 30 days, it can go from larva to adult, and a single female can lay up to 575 eggs inside corn kernels.

Would You Eat It?

The main hurdle isn’t technical—it’s cultural. Unlike grasshoppers or worms, the maize weevil is associated with filth and spoilage. “There’s a very strong cultural barrier,” explains researcher Soledad Mora. “People see it as something dirty, not as food.”

To overcome that resistance, the team suggests developing appealing products—such as snacks or gourmet dishes—that take advantage of its nutritional value.

Regulation is another challenge. At present, only the accidental presence of insects in food is allowed (and yes, even if we don’t see them, insects may already be there). To use the maize weevil as an ingredient, researchers must prove it’s safe, identify any potential side effects, and secure approval from health authorities.

A Bet on the Future

Beyond the lab, this approach could be especially beneficial for rural communities with limited access to animal protein. It also offers an eco-friendly alternative to pesticide use: instead of eradicating them, maize weevils could be collected through traps or controlled breeding, reducing both losses and contamination.

“This is about changing the paradigm,” says Silverio García. “Taking something we saw as waste and turning it into food. It’s the kind of innovation we need to face the future of food—especially over the next 10 to 15 years, when producing animal-based protein will become increasingly difficult.”

Interested in republishing this story? Reach out to our content editor at marianaleonm@tec.mx