By Luz María Alonso-Valerdi and David I. Ibarra-Zarate

Are you happy or angry? The answer may seem obvious to most children when they hear someone’s tone of voice. But for those on the autism spectrum, recognizing emotions through voice alone can be a real challenge. This difficulty can affect their daily lives — from interactions at school to relationships with family and friends.

What if the voices children with autism hear were simpler? Our study, “Improved emotion differentiation under reduced acoustic variability of speech in autism,” found that lowering the acoustic complexity of speech can help children with autism identify emotions more accurately.

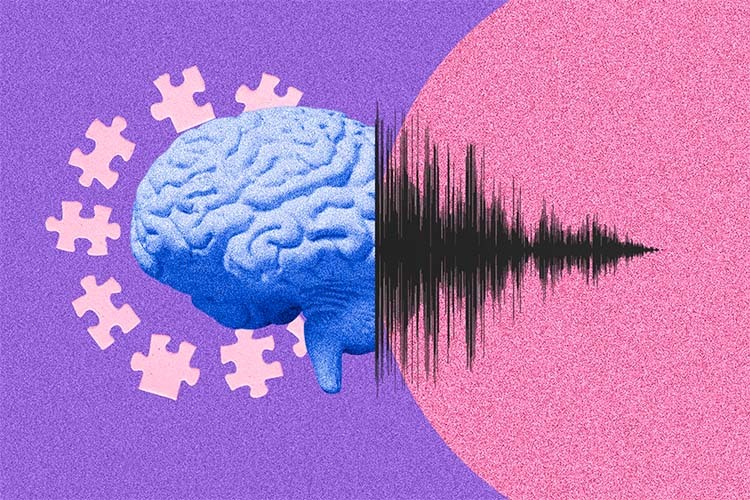

Neuroacoustics and Autism

This neuroacoustics project involved 80 Mexican children between 6 and 13 years old: 40 with autism and 40 with typical development. They listened to words spoken in six different emotions — (1) happiness, (2) sadness, (3) fear, (4) anger, (5) disgust, and (6) neutral.

While listening, the children played a visual game on a computer designed to prompt natural and spontaneous emotional responses.

The key variable was the type of voice they heard: first, natural human voices with all their pitch, tone, and rhythm variations; then, digitally modified voices with reduced variability in those features.

As the children listened and played, researchers recorded their brain activity using electroencephalography (EEG), a technique that tracks how the brain processes emotional information.

The results showed that children with autism had more trouble distinguishing emotions when listening to natural voices. But when the voices were simplified, their emotion recognition improved significantly.

EEG data also revealed that autistic children process emotional cues differently from neurotypical peers — and that more stable auditory environments enhance their perception.

In short, reducing acoustic variability creates a more predictable sensory environment that helps autistic children better recognize emotions in speech.

Simpler Voices, Clearer Emotions

The findings have direct implications across several fields. If adjusting sound complexity makes communication easier, this could translate into tangible benefits for:

- Education: Developing school materials with clearer voices to support inclusive learning.

- Therapy: Creating auditory training programs that strengthen emotional recognition.

- Technology: Designing voice assistants and apps tailored to the needs of people on the autism spectrum.

.

The study also highlights the importance of considering cultural and linguistic context when researching autism, since vocal emotional expression varies across societies.

Ultimately, a clearer, steadier voice could become a key that helps people with autism better understand others’ emotions. By learning how they perceive the world, we can design environments that foster accessibility, empathy, and inclusion

.

Reference

Duville, M.M., Alonso-Valerdi, L.M. & Ibarra-Zarate, D.I. Improved emotion differentiation under reduced acoustic variability of speech in autism. BMC Med 22, 121 (2024).

Authors

Luz María Alonso Valerdi. She earned her bachelor’s degree from the Faculty of Electronic Sciences at the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP), a master’s in Bioelectronics from the Center for Research and Advanced Studies (CINVESTAV), and a Ph.D. in Computer Science and Electronic Engineering from the University of Essex, UK. She is a research professor in Neuroengineering at the School of Engineering and Sciences, Tecnológico de Monterrey, and a contributor to TecScience.

David Ibarra-Zárate. He holds a degree in Communications and Electronics Engineering from the Escuela Superior de Ingeniería Mecánica y Eléctrica (Culhuacán Unit) at the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, and master’s and doctoral degrees in Acoustics from the Polytechnic University of Madrid and the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC). He is a research professor at the School of Engineering and Sciences, Tecnológico de Monterrey. He has worked on archaeoacoustics projects at the archaeological sites of Peralta, Guanajuato, and Edzná, Campeche.