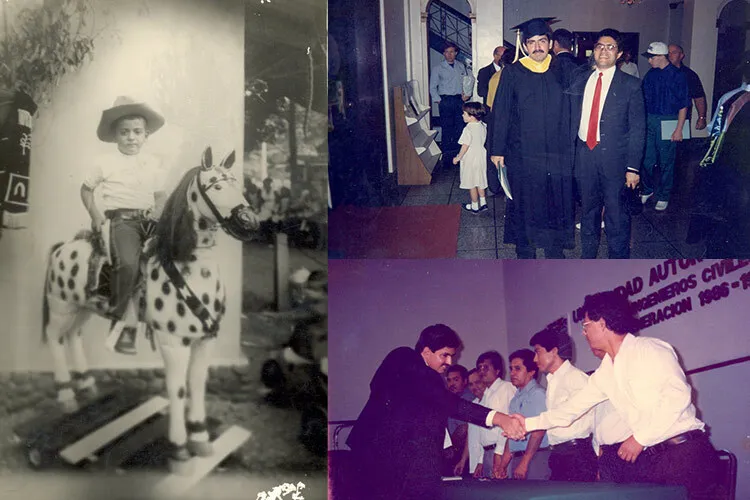

As a child, Carlos Coello used to read superhero comics, a hobby that evolved into science fiction and later computer science.

Curiously, these same topics that were fictional thirty or forty years ago (such as artificial intelligence, quantum computation, or genetic algorithms) today form part of this research professor’s work. As recently as May 2023, Coello was accepted into the National College (Colegio Nacional), the top of the tree for the country’s foremost scientists, artists, and humanists.

Born in Tonalá, Chiapas, Carlos said that much of what he has achieved in his career happened by chance and unexpectedly, although this may just be evidence of his modesty.

A member of the Tec’s Faculty of Excellence (an enterprise that unites dozens of the world’s finest teachers and researchers to share their knowledge of different areas) and a researcher in the Cinestav Computer Department at the National Polytechnic Institute (Instituto Politécnico Nacional), Coello is one of the most cited authors in engineering, has written more than 190 articles for indexed magazines, four books, and sixty chapters included in compilations.

Furthermore, he has received the most important awards given to scientists in Mexico, such as the National Award for Sciences and Arts (2012) in Physio-mathematical and Natural Sciences and the National Award for Research (2007) from the Mexican Academy of Sciences, to name but two.

Even though a list of the recognitions he has received would take up all the space available for this article and despite his undeniably being an eminence in his field of expertise, Coello has not lost his sense of humor, his simplicity, or his belief in himself. He had no qualms about opening up and telling me about his early years, about how difficult it was for him to leave his family to study abroad, and how it became even more difficult when he found out his mother had cancer and he couldn’t be by her side.

His face took on a serious pall when the camera shutter clicked but he took advantage of any lulls in the interview to smile and chat some more, as he did while telling me part of his life story.

Hobbies and Carreers

What did you want to be when you grew up?

A wrestler, but one of those who wears masks! I was obsessed with wrestling. My dad bought me some masks and we would throw a mattress down on the floor and play wrestling. Like all my friends, my favorite was El Santo (the Saint), but I never got to see him in the ring.

Once, I was ringside in the front row and a wrestler fell on top of me. As a child, everything got me excited, but one day, I realized that empty drums were placed under the ring to make the action sound louder and my enthusiasm and the magic just faded away. I was a huge fan until I turned twelve.

What replaced your passion for wrestling?

I was a fan of several things, one of which was superheroes. My mum didn’t like my dad buying me comics, but he would tell her, “He’s reading comics for the time being, but one day he’ll read other things.” And that’s exactly what happened. One day, I got bored with comics, and I started reading about science. Microbe Hunters was a great influence during my teenage years. I also read Carl Sagan, and I grew very fond of reading biographies of famous people in science and the world of computers.

I began to take an interest in movies and science fiction; for example, Isaac Asimov talked about computers and the three laws of robotics. I always thought he was a fantastic writer.

There were some wonderful books called the “Premios U”(although I have no idea how they appeared in Tuxtla Gutiérrez), which were stories written by science fiction fans. These books had a major influence on me, and my dream was to become a scientist. I wasn’t sure exactly what kind of scientist, but I knew it was something I had to do.

At first, you chose civil engineering…

I didn’t know what to study and didn’t exactly have many options in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, so I went for civil engineering, which was what I disliked the least.

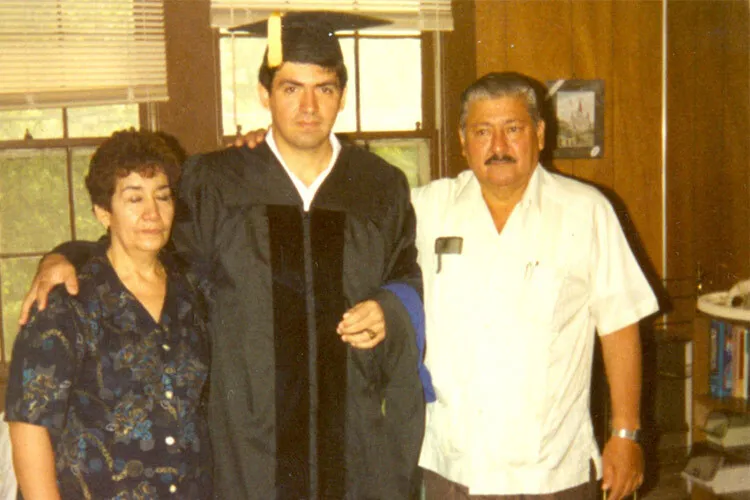

When I started studying, my dad bought me my first computer. I fell in love with computation in 1985. I realized that was what I wanted to study but I wasn’t allowed to drop out. I should tell you that my dad was a teacher at the Autonomous University of Chiapas. He had graduated high school and become a physical education teacher. It wasn’t until later that he was able to study civil engineering, and he worked as a teacher until he retired.

How did you end up in computation?

I graduated from university in 1990 and started writing my thesis… In the meantime, I got a job in a construction company. One day, I came across an advertisement for scholarships and went to Mexico City to apply for one. I had written up my résumé on a single sheet of paper and when I handed it in, the guy receiving the documents said, “I’m not sure how you’re going to get on because you’re up against this lot,” and pointed to a stack of folders bulging with thick files.

But I knew that somehow, I was going to get a scholarship. I even resigned from the construction company before I got the results. But I got nervous as time passed without any news.

Carlos Coello Coello leaned forward in his chair. He started gesticulating with his arms as if he were among a group of friends. It was the first time I had heard him laugh out loud as he went on to tell me that at one point, he thought he wasn’t going to get the scholarship.

And what happened?

But yes, yes they gave it to me and I went to Tulane University in New Orleans, where I did my master’s degree and a doctorate in Computational Sciences.

It was an abrupt change in every way, especially as far as teaching was concerned; I had to pick up a lot as I went along, but then I adapted and it became easier and easier.

The Magic of Evolutionary Computing

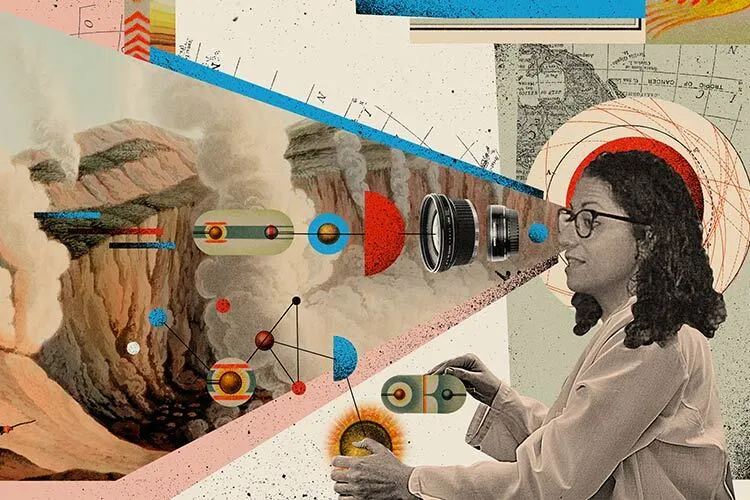

Now, you’re a pioneer in multi-objective evolutionary computation. How would you explain what it is you do?

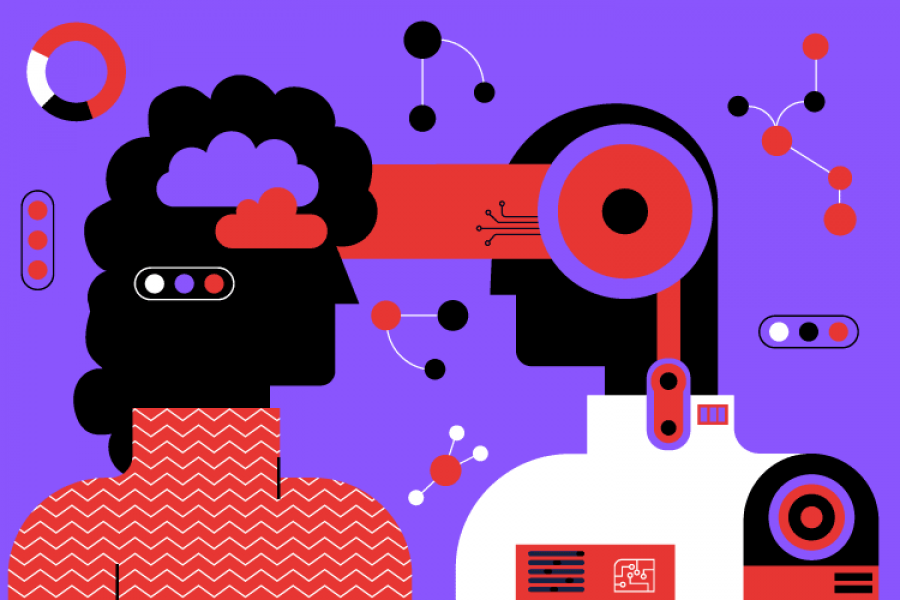

We use a set of artificial intelligence techniques to simulate natural evolution; in other words, survival of the fittest with the goal of solving complex problems, usually optimization and classification. I work in optimization.

It has many applications, from designing airplane wings and aerodynamic car profiles to the optimization of train schedules and package delivery routes.

Carlos’s work has been used in supersonic jet design and even an autonomous aircraft to take photographs of the surface of Mars.

You work with stochastic algorithms. That sounds really weird!

Evolutionary algorithms are stochastic; in other words, their operation is based on the use of random numbers. It sounds a bit strange, especially in computation, because we’re used to seeing an algorithm produce the same result if the same data is used in the equation.

These algorithms don’t work like that because we’re simulating biological processes; like in nature, where there is a certain degree of uncertainty and outcomes are not always precise.

You created the first genetic algorithm around the year 2000. What is that, and how was it developed?

It was an idea I’d been chewing over that I got from an article I read back in the eighties, which propounded that, theoretically, a genetic algorithm couldn’t possibly work in a small population.

In other words, they believed that the final solutions at any given time would be the same. To avoid this, the population size is increased; therefore, in theory, it wasn’t possible to have both: a small population and different outcomes. We managed to do it.

It was very innovative at the time. I collaborated with a brilliant student called Gregorio Toscano and the algorithm worked. It was very fast for its time.

Challenging Expectations

Your work has won you many recognitions and an invitation to become a member of the Colegio Nacional. What was that event like?

It was surreal. Let me tell you why. After I gave my acceptance speech, a journalist came up to me and said he was amazed that someone with a profile like mine had been invited to become a member of the National College… and he was right: he wasn’t exaggerating.

The Colegio Nacional has brought together Mexico’s foremost scientists, intellectuals, and artists. Members have included Diego Rivera, Nobel Prize winners like Octavio Paz, and great writers like Carlos Fuentes.

When I went to my first members’ lunch, I was asked if was from the Polytechnic Institute, the Tec, or the UNAM… Many had no idea there was an Autonomous University of Chiapas. I was from a small university and the university where I completed my studies in the U.S. was hardly one of the most renowned.

Coello laughed again, louder than before, and cleared his throat.

Did that make you feel uncomfortable?

No, I was honored. You look back on your life and think, “How very odd! How could something like this happen to me?”

If you had asked me as a young man, I would have said it could never happen, but as I grew up, I felt I could achieve more, through hard work, obviously, and also the stars aligning.

All said and done, I feel very fortunate.

What else makes you feel fortunate?

Well, I’m the father of two: the younger of the two has just turned twenty-two and the older one is twenty-six. And I’m very happily married. My first son gave me the wonderful surprise of receiving the University Medal of Merit and I am very proud of him.

My mother has retired and lives in Tuxtla Gutiérrez. She always tells me that if he were alive, my dad would be proud too. I talk to my mother at least once a week. I travel a lot and am sometimes on the other side of the world, but I always try to call her. She was always very supportive and moved mountains to make sure I had everything I needed.

How would you like to be remembered when you’re gone?

I went into a three-day depression on my fortieth birthday, but I got over it quickly. But when I turned fifty, I started thinking about my legacy. People say that when you turn sixty, you start thinking, “Just as well I’m still alive”.

I think that, all things considered, we’re lucky if we have at least one or two transcendental achievements. I also believe that sometimes you are not remembered for what you enjoyed most in life. It could happen; at the end of the day, people may remember me for some of the relevant things I did they are currently unaware of.