By Claudia Sofía Carrera and Valeria Estudillo

Reviewed by Carlos Enrique Guerrero

The climate is changing—and so is everything around us: the crops, the landscapes, the cities… and even your body.

Extreme climate variations create environmental conditions that push our physiological limits, and our bodies are beginning to send warning signals. Deep inside us, a pair of vital organs—the kidneys—face a tremendous challenge: surviving in an increasingly unpredictable world.

We hear almost daily about melting poles and species extinction, but what rarely gets attention is how our bodies are being affected by these changes.

Climate Change and Your Kidneys

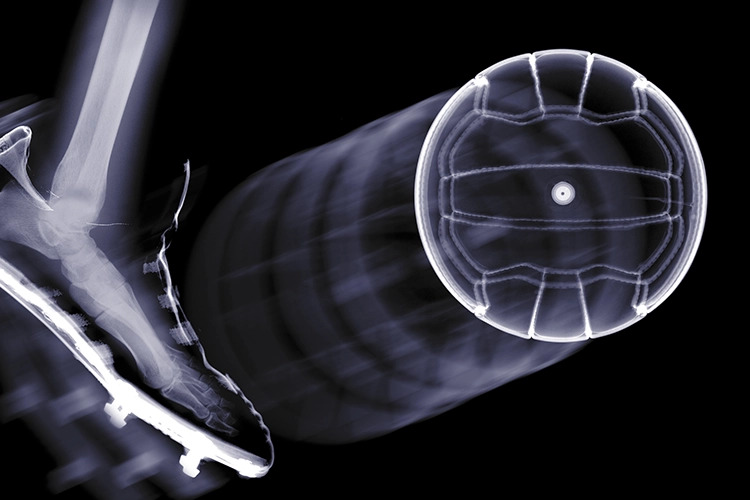

Kidneys are bean-shaped organs that perform a critical function: filtering and removing waste from the blood through urine. This process is precise and essential. Yet with ongoing environmental changes, our kidneys can become disoriented, and chronic stress may lead to permanent damage.

Temperature changes induced by climate change aren’t the only factor affecting kidney function. A cascade of related phenomena—extreme weather events, constant environmental shifts, and biodiversity loss—also impacts the body.

Emerging heat waves, droughts, and chronic dehydration are growing threats to kidney health. Our bodies lose more water through sweat and urine. At the same time, metabolic processes generate new waste products, disrupting the body’s stable internal environment and threatening homeostasis—the ability of organisms to maintain internal balance and regulate themselves.

When this happens, there’s less fluid to dilute and remove waste, making the blood more concentrated and allowing toxins to accumulate—like making lemonade with too little water and too much sugar. This constant cycle overworks the kidneys, forcing them to operate under increased pressure and eventually wear down.

This is not the dehydration you feel after a morning run on a sunny Sunday that disappears once you drink electrolytes. This is chronic dehydration from living in dry, hot, or extremely humid conditions.

Though it may seem harmless, this condition is associated with a higher risk of kidney damage. In fact, atypical forms of chronic kidney disease have been identified in certain parts of Central America, underscoring the dangers of extreme heat and persistent dehydration.

What about concentrated urine? Surprisingly, it promotes the formation of kidney stones. These tiny crystals can block filtration—like clogging a household pipe—causing pain and infections.

Prolonged dehydration triggers body mechanisms that can disrupt cellular chemical balance. One consequence is increased oxidative stress, a condition in which cells produce more free radicals than they can handle.

Free radicals are unstable, highly reactive molecules that damage healthy cells by “stealing” electrons in an attempt to stabilize themselves. This leads to inflammation and cell death in kidney structures, particularly the nephrons, contributing to chronic kidney disease.

Kidney Defense Mechanisms

Our kidneys suffer silently—but they also fight back. The first responders are the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and the hormone vasopressin.

Together, they regulate fluid balance and act as an emergency alarm system, telling the kidneys how much water to conserve to maintain blood pressure and body fluid volume.

The problem occurs when these alarms are triggered continuously. Vasopressin also drives excess fructose production in the kidneys. Unlike the fructose found in soft drinks, this internally produced sugar generates more free radicals, which damage cells, turning a helpful molecule into a harmful one when overproduced.

Fortunately, our bodies have built-in defenses against heat and metabolic stress, known as heat shock proteins (HSPs).

These proteins prevent damaged macromolecules from accumulating, helping repair them—a key function considering how abrupt temperature changes, heat, and dehydration directly affect cells. In the kidneys, HSPs stabilize cells, prevent cell death, and coordinate with other protective proteins to regulate antioxidant defenses and inflammatory responses.

Another defense comes from sirtuins, proteins that maintain metabolic and internal balance. Sirtuins detect stress, activate genes that repair DNA and oxidative damage, suppress inflammation, regulate heat production, and optimize energy use.

They also protect kidneys by moderating RAAS overactivation, inhibiting crystal formation, and supporting glucose metabolism and antioxidant processes.

Between Resilience and Damage

So, if our bodies have ways to protect themselves, why the urgency?

Unfortunately, climate change is a formidable challenge. Some heat shock proteins have been linked to cell damage, inflammation, and cell death. When present in excessive amounts, these proteins may lose their protective effects, harming the kidneys and contributing to other conditions such as type 2 diabetes, heart failure, and autoimmune disorders.

These defense mechanisms are clearly a double-edged sword, and scientists are still working to understand their full impact.

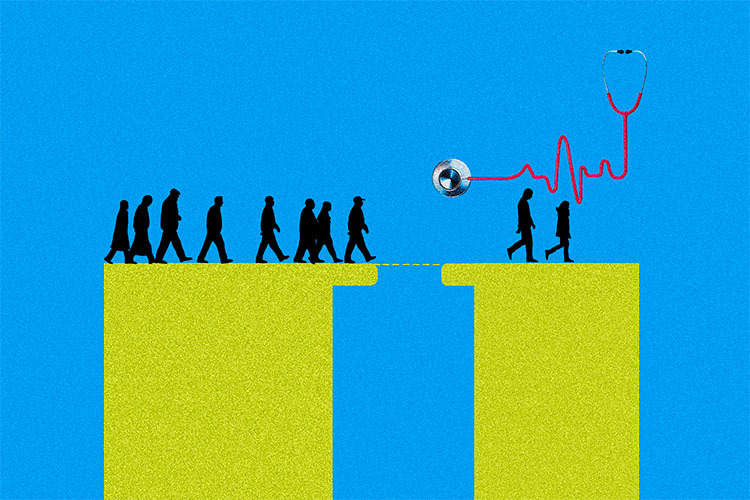

Extreme heat and cold waves spare no one—your job, your comfort, or your environment don’t matter.

Beyond understanding the link between the environment and our organs, studying protective mechanisms like HSPs and sirtuins opens doors to potential new therapies that could safeguard our kidneys in a warming world.

.

References

- Molecular Challenges and Opportunities in Climate Change-Induced Kidney Diseases. Luna-Cerón, E., Pherez-Farah, A., Krishnan-Sivadoss, I., Guerrero-Beltrán, C.E., 2024, 14(3), 251.

- Heat shock protein 60 and cardiovascular diseases: An intricate love-hate story. Krishnan-Sivadoss, I., Mijares-Rojas, I.A., Villarreal-Leal, R.A., … Knowlton, A.A., Guerrero-Beltrán, C.E., 2021, 41(1), pp. 29–71.

- Vaccines against components of the renin–angiotensin system. Garay-Gutiérrez, N.F., Hernández-Fuentes, C.P., García-Rivas, G., Lavandero, S., Guerrero-Beltrán, C.E., 2021, 26(3), pp. 711–726.

- HSP60-Derived Peptide as an LPS/TLR4 Modulator: An in silico Approach. Vila-Casahonda, R.G., Lozano-Aponte, J., Guerrero-Beltrán, C.E., 2022, 9, 731376.

- Peptidic vaccines: The new cure for heart diseases?. Guerrero-Beltrán, C.E., Mijares-Rojas, I.A., Salgado-Garza, G., Garay-Gutiérrez, N.F., Carrión-Chavarría, B., 2021, 164, 105372.

.

Authors

Claudia Sofía Carrera Lozano. Eighth-semester undergraduate student in Biomedical Sciences at Tecnológico de Monterrey.

Valeria Estudillo López. Fifth-semester undergraduate student in Medicine (M.D. program) at Tecnológico de Monterrey.

This article was supervised by Enrique Guerrero Beltrán, research professor at the School of Medicine and Health Sciences at Tecnológico de Monterrey, who holds Level 2 status in the National System of Researchers of the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation (SECIHTI).