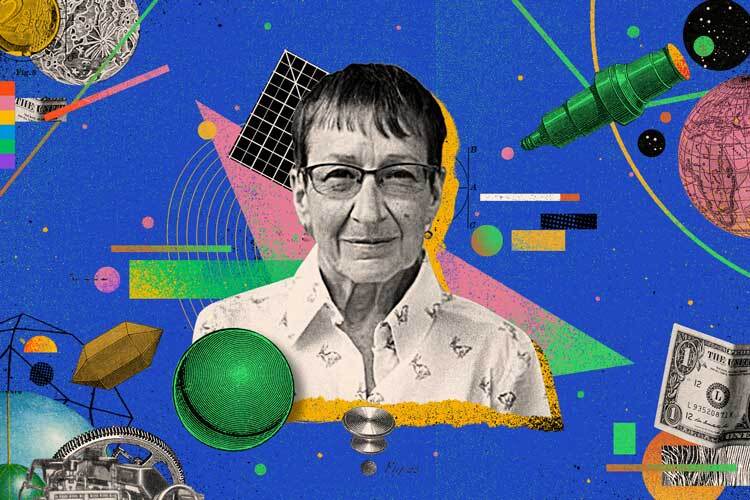

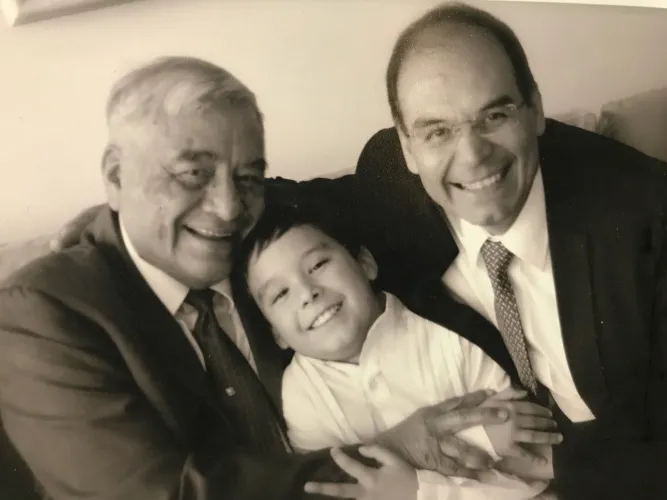

While I walk alongside Arturo Molina on the Tec de Monterrey’s Mexico City Campus, some people approach him, some with affection, others with admiration. Evidently, he’s an essential member of the Tec community, where he has cultivated most of his career.

From a curious child with an insatiable thirst for building things, to a young man who, when choosing his career, told his father he wouldn’t become a doctor, as his father wished, because he wanted to be the best engineer. And he succeeded. After pursuing a bachelor’s and master’s degree in Computer Science at Tec, a Ph.D. in Mechanical Engineering at the Technical University of Budapest, and a second Ph.D. in Manufacturing Engineering at Loughborough University, England, he is now considered one of Mexico’s most renowned researchers in materials and manufacturing processes.

His work has led him to become a level-three member of the National System of Researchers (SNI) and receive awards such as ARIS or QS Reimagine Education Nurturing Employability. But for Arturo Molina, Director of the Institute of Advanced Materials for Sustainable Manufacturing (IAMSM), awards are not the ultimate representation of success. For him, there is no more extraordinary achievement than inspiring his students to conduct research and give something back to society.

The Tec and the Rómulo Garza

This isn’t the first time Molina has been awarded the Rómulo Garza. In 2009, he won second place in the Publication Category, and in 2014, in the Recognition Category for Scientific Articles. However, winning it this time feels special because the Insignia award is the highest recognition Tec grants to a researcher’s trajectory.

Congratulations! How did you receive the news of the award?

It was a moment of great happiness and satisfaction. Also, I am grateful to Tec for allowing me to be a researcher in Mexico, which is challenging given the country’s circumstances and history.

How has it been for you to develop your career at Tec de Monterrey?

I arrived at Tec with a scholarship to study for my bachelor’s degree, and it taught me many things —first, the discipline of learning. I had many friends who were exceptionally brilliant but undisciplined, and I’m not very clever but disciplined. The second was responsibility; you have to deliver things when promised. The third is to remain curious. We always had access to things that piqued our curiosity and professors who encouraged it.

How do you think Tec has changed?

It has evolved into a more humanistic model in its academic programs and community work, and research and innovation have also grown significantly. What has always been a hallmark is the talent of its professors, people who inspire and are committed to teaching.

Industry and sustainability

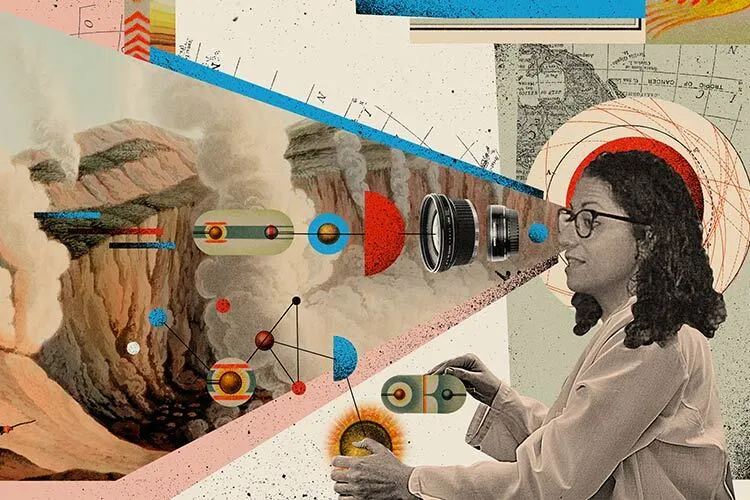

Arturo Molina is not only the Director of the Institute of Advanced Materials for Sustainable Manufacturing; he was also in charge of designing it, a process that took several months and interviews with key individuals worldwide. The Institute’s goal is to aspire for the industry to be effective, innovative, and sustainable simultaneously.

How would you describe what you do and what are you an expert in?

I’m a Computer Systems Engineer, but I was interested in applying Computing to Machine Tool Automation. My work is very mechatronic; I combine computer systems engineering, mechanics, and manufacturing processes.

How did you become interested in this?

Since childhood, I have been involved in carpentry, fixing cars, and assembling scale models of airplanes and cars. As I grew older, I became interested in computing because I saw great potential. Then, during my studies, there was a project to automate a manual milling machine, and that’s when I realized I wanted to do research.

Why are materials so important?

Everything around us is made of materials, and in Mexico, manufacturing is essential, representing 17% of GDP and employing more than nine million people. Materials have to be processed and transformed with energy, water, and gas, so it’s about working on both their design and manufacturing to save energy, resources and reduce emissions, pollution, and waste.

What are disruptive technologies, and how can they help build better cities?

They are nanotechnology, biotechnology, information technologies, and cognitive sciences. Nanotechnology is allowing us to generate a new generation of more sustainable, intelligent, and safe materials exponentially. Everyone is talking about AI, but many other technologies will transform how we live.

Balance above all

Although his achievements suggest that Molina dedicates all his time to work, the researcher’s priority is his family and friends, and he seeks to achieve a balance by setting rules and structured schedules. “During the week, I try to finish at six in the afternoon; on weekends, I’m only dedicated to my family.”

Besides science, what else are you passionate about?

I like music; my favorite bands are Journey, Queen, and Abba. I also play the guitar, not very well, but I enjoy it and compose ballads for my wife and children. When we were young, my friends and I had a trio, and we used to serenade their girlfriends. That’s where my interest began.

I’m also a collector; since childhood, I have collected stamps, Kaliman magazine issues, keychains from countries I’ve visited, and other things.

Tell me about your family.

My wife and I will celebrate 35 years of marriage. We went to Europe together; she did her master’s, and I did my Ph.D., and we both pursued professional careers. We waited a long time to have our first child. We have been through many moments of happiness and other difficult ones. Each of us has to make the effort to evolve. In general, we understand each other; we are very close friends, good lovers, and we like many things in common.

My children, Julio, 17, and Montserrat, 15, have taught me many things, such as being more understanding, listening, or becoming interested in things I had never thought of. They have taught me to approach situations with emotions first and to be empathetic.

Approaching society

Molina, born and raised in Oaxaca until he was 18, learned the importance of contributing to the society we belong to. “Tequio means that if you leave Oaxaca and are successful, you must give back to your community,” he explains.

You mention the commitment of scientists to society a lot.

My parents were always interested in helping the community. My mother was an educator and created an indigenous education program called “Niño a Niño,” which became a civil association named Vidas y Sueños, operated by all my siblings. My father attended to many people from indigenous communities, so we learned this from a young age.

Since junior high and high school, I taught Mathematics and Spanish to adults because I thought I could help with literacy. At Vidas y Sueños, we organize educational events, collect groceries, and recently installed rainwater harvesting tanks.

Who has inspired you in your work as a scientist?

On one hand, my father. He was a gynecologist, obstetrician, and empirical researcher who instilled in me that being a researcher is a responsibility. On the other hand, during my master’s degree, I was fortunate to have a class with Héctor García Molina, an EXATEC and professor at Stanford, who inspired me in how he taught and his projects.

What’s a notion about scientists that might be mistaken?

We’re often labeled as not understanding society, but we are responsible for changing this perspective. We must communicate our work in a way that people understand. If you don’t communicate, if you lack empathy, if you don’t make the effort, you have unfinished business.